What’s Behind Japan and South Korea’s Latest Attempt to Mend Ties?

The two countries will have to overcome historic grievances to address common security and economic interests.

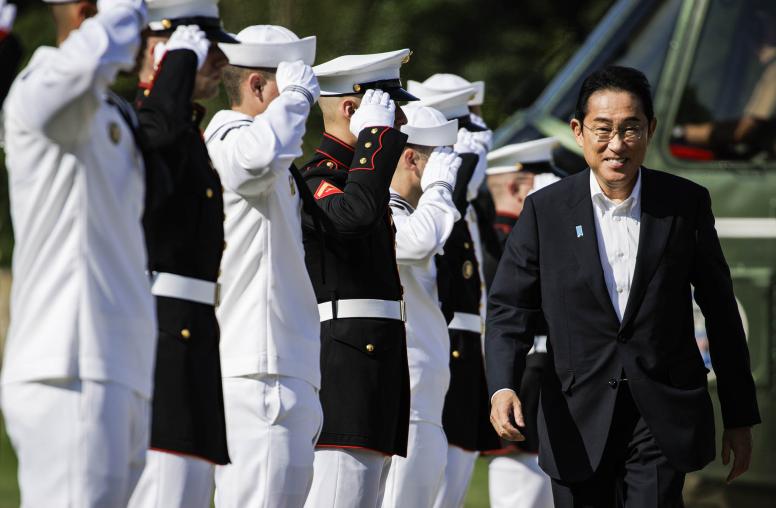

The meeting between South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida earlier this month — the first bilateral summit between South Korean and Japanese leaders in over a decade — was welcomed by both sides as a major step toward renewing relations. Despite ample common cause on issues such as regional security and economic growth, ties between the two countries have been strained in recent years over unresolved disputes stemming from Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea.

Yoon and Kishida are by no means the first leaders to try to rebuild the bilateral relationship, and past attempts have failed to provide the kind of long-term closure that would put the historical tensions to rest. But given the acrimonious give-and-take between the two countries in recent years, this month’s summit offers a sign of sorely needed rapprochement as the two U.S. allies seek to address an increasingly belligerent North Korea and China’s growing presence in the Indo-Pacific. USIP’s Frank Aum and Mirna Galic break down the latest agreement, the reaction from South Korean civil society, and what improved security cooperation between South Korea and Japan means for U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific.

What is driving this latest push for South Korea-Japan reconciliation?

Aum: For decades, both countries have recognized the need to settle past historical issues from the Japanese colonial period and improve their diplomatic and economic ties in order to address common challenges.

However, past agreements meant to resolve their differences, such as the 1965 normalization treaty and claims agreement and the 2015 comfort women agreement, were often vague or paid insufficient attention to victims’ concerns for the sake of political expediency and national goals. These agreements allowed the two countries to improve relations sufficiently enough to achieve gains in security, development and prosperity. But because they didn’t resolve fundamental questions about the colonial period, the agreements remained controversial — subject to different interpretations and recurring risks of collapse.

For example, two 2018 South Korean Supreme Court decisions stated that Japanese companies must directly compensate Korean victims of forced labor — a ruling that challenged Japan’s interpretation of the colonial period and the 1965 claims agreement. The decision quickly strained bilateral relations, upended economic ties and threatened security cooperation between the two countries.

The latest agreement by the Yoon and Kishida governments may be following the same unfortunate pattern. With both countries facing similar challenges in recent years — including Chinese coercion, North Korean belligerence, weak economic growth, inflationary pressure, supply chain resilience and climate change — there is significant incentive for the two to work together.

The recent bilateral deal attempts to mend relations and restore cooperation by compensating South Korean forced labor victims through a foundation made up of funds from South Korean companies, rather than Japanese ones. This is meant to ease tensions over the 2018 South Korean Supreme Court cases and allow Japan to maintain its argument that all claims had been settled by the 1965 treaty and therefore Japanese companies do not need to provide compensation.

The deal, at least at the governmental level, appears to be working: It facilitated President Yoon’s visit to Tokyo last week — the first bilateral summit between the two countries’ leaders in 12 years — where they agreed to resume reciprocal diplomatic visits and security dialogues, normalize an intelligence-sharing agreement, and take steps toward resolving ongoing trade disputes.

Japan also lifted export controls on South Korea related to three chemicals necessary for its high tech industries. And business federations in both countries announced that they would contribute funds to support youth scholarships and cultural exchanges.

How have South Korean civil society and victims’ organizations reacted to the Yoon government dropping demands for Japanese companies to compensate victims?

Aum: While the agreement might be working for the Yoon government, multiple polls also show that about 60 percent of the South Korean public opposes the agreement, suggesting that it may not provide the closure that both governments are seeking.

The Yoon government may have determined that the agreement, while disappointing for the forced labor victims, was the best deal possible given Japan’s refusal to accept their claims. But at least three of the 15 forced labor victims who have pending legal cases against Japanese companies have refused to accept any money that does not come from these companies directly. They have also brought a new suit to collect money from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, one of the Japanese companies involved.

And while Japanese Prime Minister Kishida reaffirmed the 1998 declaration in which Japan expressed remorse for its colonial rule, critics have complained that the Japanese side didn’t provide a sincere apology. One victim, Kim Seong-joo said, “We can forgive, if Japan tells us one word, we are sorry and we did wrong. But there’s no such word.” Claims by Japanese politicians that Japan is “a victim caught up in the [lawsuit]” or that the deal was a “total victory for Japan” because “we didn’t have to concede anything” have only rankled South Korean critics further.

The agreement’s inability to address the victims’ concerns raises legal issues that may cause it to fall apart, similar to previous efforts. By law, the claimants must consent to having a third-party satisfy a debt for the deal to proceed. If the victims do not consent, then it is unclear how the South Korean Supreme Court will resolve the pending cases that, based on previous rulings, might allow for the seizure and liquidation of Japanese company assets.

Any court decision that delays or impedes a favorable ruling for the victims based on the political agreement might raise concerns about judicial independence, but a decision by the relevant Japanese companies to voluntarily contribute funds to the foundation may help persuade the victims to accept the funds.

What would improved military cooperation between Japan and South Korea mean for U.S. efforts in the Indo-Pacific? What reaction might we see from China or North Korea?

Galic: Reinvigorating security ties between their countries was reportedly on the agenda for Yoon and Kishida during their meetings in Tokyo. This includes intelligence sharing, the resumption of bilateral security dialogues suspended since 2018, and, potentially, the establishment of an information-sharing framework on North Korean ballistic missile launches. All of these activities would most benefit Japan and South Korea themselves, but the United States will gain from any increased security ties between its two allies as well.

Intelligence and information sharing between Japan and South Korea would increase deterrence against North Korea — something of direct interest to the United States — especially since Japan has enhanced its domestic capability to respond to attacks. Increased bilateral military cooperation between Japan and South Korea could also lead to increased trilateral military cooperation between these countries and the United States.

More broadly, the entire U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy rests on working in concert with allies and partners in the region. It’s easier to align our approach to bolstering Indo-Pacific security and advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific — two of the goals of the administration’s strategy — if our partners in the region are also able to work more closely together on such issues. The message this sends about ally unity and the ability of the United States and its allies in the region to overcome difficulties for the sake of shared priorities is also important.

So Yoon and Kishida’s efforts to mend ties between their countries are generally seen as a plus from the perspective of the U.S. government, which has been consistently encouraging the two sides and strongly welcomed the leaders’ initiative.

Not so much North Korea. The North Korean regime registered its displeasure by launching an intercontinental ballistic missile on the first day of the summit. Certainly, North Korea would prefer for Japan and South Korea to be divided and less able to coordinate than united and cooperating. China’s official response, meanwhile, has been muted, which makes sense: It would be difficult for Beijing — which is intent on portraying itself as a global peacemaker — to publicly criticize two neighboring countries for trying to improve their bilateral relations.

The United States is allied with both Japan and South and has played a significant — yet sometimes counterproductive — role in mediating tensions between the two countries. How should the United States approach this latest effort in order to have a positive impact?

Galic: Bringing Japan and South Korea closer together has long been a priority for the Biden administration, which explicitly included the goal in its Indo-Pacific strategy. The United States no doubt encouraged the leaders to meet together behind the scenes and U.S. shuttle diplomacy between the two countries has been credited with helping to bring about the summit.

The United States also issued Yoon an invitation for a coveted state visit after the summit was announced, perhaps in an attempt to bolster his domestic standing. Continued U.S. positive reinforcement and support of this kind for both Japan and South Korea will be important as the countries navigate the complicated issues that underpin tensions between them. What’s difficult is that although the United States can express support for and perhaps influence the efforts of the two governments, it doesn’t have sway over the views of the Japanese and Korean publics, including the Korean victims groups, which ultimately need to support their governments’ initiatives.

Aum: All U.S. administrations, including the current one, have tended to strongly support Japan-South Korea reconciliation that facilitates future-oriented cooperation on diplomatic, security and economic matters.

This recent agreement is no exception. However, if the three countries want an enduring, final resolution to the historical issues that both minimizes the potential for periodic eruptions of strained relations and maximizes the potential for optimal bilateral cooperation — perhaps even a bilateral South Korea-Japan alliance — then they should pursue measures that give the victims appropriate closure and compensation, reconcile competing views of history as much as possible, and provide proper commemoration and education for future generations.