A Guide to Understanding the History of the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue

To help Seoul and Tokyo mend ties, U.S. policymakers first need to learn the nuances of an important ‘memory battle.’

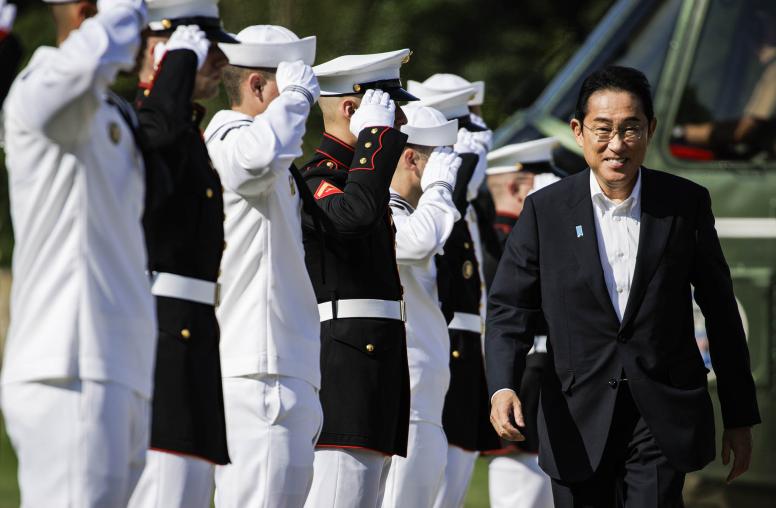

Even before assuming office in May 2022, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol made clear his desire for smoother formal relations between Seoul and Tokyo. Locked in a number of interwoven and protracted disputes, South Korea and Japan have been at a diplomatic standstill since well before COVID-19 restrictions shut down everything. Recent peacebuilding efforts are encouraging, with Japan and the United States publicly welcoming South Korea’s overtures as pivotal to plans for regional alignment in the face of North Korea’s provocations and China’s aggressive behavior.

Nonetheless, significant difficulties remain. Washington’s desire for calmer trilateral waters runs directly into an unfortunate approach to what are collectively referred to as the “history problems.” Today, 80 to 100 years removed from the events involved, these rancorous disagreements are better understood as “memory battles.” Among them, one of the most fraught issues remains the history from the 1930s and 1940s commonly known by its cruel euphemism: the “comfort women.”

U.S. policymakers must understand three key aspects of the comfort women issue if the United States is to play a helpful role in resolving bilateral tensions between Japan and South Korea.

Background

Beginning in 1932 and lasting until 1945, the Japanese government’s notorious systematized sex trafficking scheme involved women, girls and boys from throughout the Japanese empire. Scholars believe the system ensnared 200,000 victims, although estimates vary from 20,000 to nearly 500,000. However, it is not the numbers that continue to teach us. The history happened, and we learn from the ways in which Japanese state apparatuses functioned, often in conjunction with one another, to organize the system. The best current research is being done in China through collaborative efforts with scholars there working with colleagues in Japan (such as Etsuro Totsuka and the Tokyo-based Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace’s Mina Watanabe), South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, Germany, the United States and beyond. In short, an international effort to understand and analyze this past has been at work since the early 1990s, and it is important to recognize up front this issue as a global history and phenomenon.

The truth of the “comfort women” history is not the issue at hand. Nevertheless, Holocaust-like denialism continues to attack this history and labels victims “liars” or “money grabbers” and whitewashes most evidence as “fake” despite abundant academic and juridical peer-reviewed material as well as governmentally published documentation that verifies the litany of horrors during this shameful episode. Additionally, there are significant multinational, multiethnic survivor testimonies, and the few living survivors are still sufficiently strong and tell their stories as well as their ongoing struggles. In the mix, a vicious cycle of blame and recrimination remains on all sides, which, in turn, continues to harm the few survivors of a history that ranks at the top of the 20th century’s instances of wartime state-sponsored militarized sex trafficking.

For those new to the issue of South Korea-Japan tensions — and especially those working on policies to improve regional relations — it is important to understand that Washington has been, and continues to be, very much in the middle of multiple attempts to unravel disputes between Tokyo and Seoul. To be clear: This does not mean that the United States is responsible for creating the histories involved. Yet, Washington policymakers and practitioners continue to play a central role, which is why deniers and advocates alike want Washington to take clearer positions for their position’s respective gain. As a result, it has never been more important for U.S. government practitioners to understand three key, yet often obfuscated, pieces of the “comfort women” history in particular.

‘Comfort Women’ Versus ‘Sexual Slavery’

First, words matter. Avoidance of the term “sexual slavery,” which has already been ascribed to this history by the United Nations and the Obama administration, amounts to allowing the Japanese government to shirk state responsibility for state sponsorship of what is defined as a war crime and crime against humanity. In the summer of 2012, then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton remarked that the U.S. government understood this matter as “sexual slavery” according to global norms. The backlash among some Japanese nationalists began then with a vengeance and has not let up.

Deniers brand as “anti-Japanese” or “pro-Korean” anyone who researches or publishes about this sordid history — as Russian officials now do in an attempt to defame those investigating what is taking place in Ukraine.

Imperial Japan’s state sponsorship in the 1930s and 1940s of human trafficking of minor children and women for the purposes of sex from Japan and its overseas territories and war zones remains among the 20th century’s largest examples of the horrendous practice of state-sponsored militarized sexual slavery. Today, the United Nations is examining similar instances of Russian soldiers allegedly committing sexual violence in Ukraine and labeling the cases accordingly, and this is why words matter.

The Transnational Nature of Imperial Japan’s Sexual Slavery

Second, although Japan’s historical state sponsorship of militarized sexual slavery is frequently and unproductively portrayed as an issue between South Korea and Japan, with parties in both countries bearing responsibility for this problem, the issue is much broader. The historical sexual slavery system that operated in the 1930s and 1940s occurred throughout the entirety of the Japanese empire, beginning in Japan and extending to its colonies and war zones as the battles expanded until Japan’s defeat in 1945. Recruiters for the Japanese government worked in countries including but not limited to Korea (there was no South or North at the time), China, Taiwan, Japan proper, East Timor, Vietnam, the Micronesian islands (including Guam, where U.S. citizens were ensnared), the Philippines, Indonesia, Myanmar and Cambodia.

Most frequently forgotten in the politicization of this issue is that the first known “comfort women” were Japanese. In 2006, Totsuka, one of Japan’s preeminent international legal theorists and historians, analyzed the well-documented 1932 trafficking case of 15 Japanese women by Japanese men through Nagasaki to one of the first known “comfort stations” established in Shanghai by the Imperial Navy. Totsuka maintains that this evidence should encourage further research to understand why the Japanese penal codes against abduction and kidnapping that were applied in that case “[were] not effectively enforced in Japanese colonies, particularly in Korea” since “the pattern of recruitment [in Japan] (was) strikingly similar to the many Korean cases of the abduction of women.” Moreover, Totsuka’s efforts, together with the efforts of many others, underscore that understanding past state-sponsored atrocities can help prevent ongoing occurrences of similar violence in the present. This is one reason why and how the international community is able to respond in real time to reports of sexual violence committed by Russian soldiers in Ukraine.

Comfort Women Statues

Finally, U.S. policymakers should examine why Tokyo is contesting comfort women statues in several countries. Since the December 2011 unveiling of the first statue directly across from the Japanese Embassy in Seoul — a benign likeness of a seated girl that invokes the victims’ lost childhoods — these statues have been the gathering touchstone for South Korean and other survivors. A South Korean civic group sponsored the first one to mark the 1,000th consecutive weekly demonstration that victims and their supporters have held, and continue to hold, since 1992. Japanese diplomats made their discomfort with the statue known as soon as it appeared.

Hundreds of demonstrations later, the peaceful girl statue is elemental to how many people commemorate and educate this history’s trauma. Over 40 similar statues exist throughout the world in South Korea, the United States, China, Australia, Germany and Canada. One in Shanghai includes a Chinese victim seated next to a Korean girl. Another in San Francisco depicts a Filipina holding hands with Korean and Chinese girls. Survivors embrace the statues, and supporters wrap them in scarves in the winter and decorate them with garlands of flowers in the summer. Three successive South Korean administrations have refused Japan’s request that the statue be torn down in Seoul, making all the more alarming Tokyo’s ongoing efforts to make the statue disappear.

Today, it is commonplace for groups around the world to demand the removal of statues of historical figures deemed to be perpetrators of criminal acts. Only Japan is seeking the removal of statues representing victims of its past crimes. Japan’s efforts are additionally unusual because the country is seeking to redefine its security posture to allow its troops to engage militarily abroad for the first time since 1945. How do we understand Tokyo’s desire to enhance its military’s legitimacy and capabilities when its leaders seek to eradicate statues that symbolize the imperial military’s shameful history? Neither the Japanese nor the South Korean government should intervene with the statues. The survivors and their supporters should decide where they belong and what they reflect, and those managing any agreement about this history must listen to them for the agreement to work.

Alexis Dudden is a professor of history at the University of Connecticut.