South Korea and Japan Need to Reset Relations. Can the United States Help?

Biden’s upcoming visit offers an opportunity to help U.S. allies mend ties.

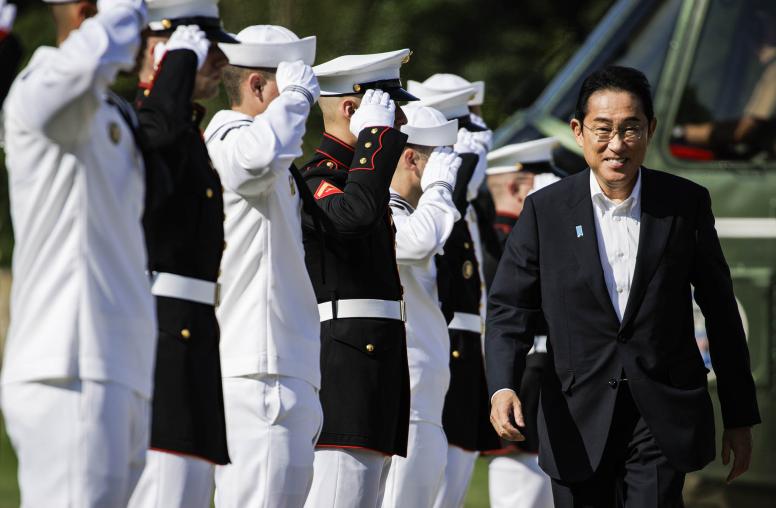

In April 2022, a South Korean delegation representing President-elect Yoon Suk-yeol met with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in Tokyo to help reset bilateral ties that have frayed in recent years over unresolved issues like wartime forced labor and sexual slavery. The delegation head told reporters that the trip’s goal was to fasten “the first button of a new Korea-Japan relationship,” referring to the proverb that incorrectly fastening the first button on a jacket will cause subsequent ones to go astray.

Yoon may have intended that trip to set the first button for smoother future relations, but two 2018 South Korean Supreme Court decisions suggest that the problem goes back to 1965. Those verdicts directly challenged Japan’s interpretation of the 1965 Claims Agreement, the foundation for post-war Japan-South Korea relations. How the two countries resolve this fundamental issue will impact not only the future of bilateral relations but also the success of the United States’ Indo-Pacific strategy. The potential ways forward, however, appear bleak without an extraordinary shift in position from Tokyo, Seoul, or both. President Joe Biden’s trip to the region in late May presents an important opportunity for Washington to nudge its allies toward a resolution.

Background on the South Korea-Japan Forced Labor Issue

In 1997, two South Korean plaintiffs filed suit in Japan against Nippon Steel Corporation for forced labor that occurred during World War II when Japan ruled over Korea. They argued that they were recruited under false advertisement, were not paid their due wages and were subjected to unsafe working conditions. The lower court dismissed the suit in 2001, and the Japanese Supreme Court denied the final appeal in 2003. The courts held that, while the company (described here as “Old Nippon Steel,” later reorganized into Nippon Steel) mistreated the plaintiffs as they described, Nippon Steel did not carry Old Nippon Steel’s liability. The courts added that, in any case, the plaintiffs’ claims were extinguished by the 1965 Claims Agreement. The plaintiffs later pressed the same claims in South Korea, where lower courts in 2009 also dismissed the suit, citing the Japanese rulings and the expiration of the statute of limitations.

Since 2001, the Japanese government has reiterated its courts’ argument regarding the victims’ claims. The government asserts that under Article I of the Claims Agreement, Japan was required to provide South Korea with $300 million in grants and $200 million in loans, and that under Article II, the problem concerning “property, rights and interests” as well as “claims” between the two countries and their nationals were “settled completely and finally” and no contention could be made regarding those claims. Some scholars have noted that the scope of these claims also encompassed the eight items explicitly raised by South Korea during the Claims Agreement negotiations, one of which related to “amounts receivable, compensation, and other rights of claim of drafted South Korean workers.”

However, the 2005 release by then-South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun’s administration of the Claims Agreement negotiation records led to a different interpretation. A private-public commission’s review of the records found that the agreement was “not primarily intended to address reparations for Japanese colonial rule, but rather to settle the financial and civil claims and debt relations” between the two countries pursuant to Article IV of the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty. In other words, unlike Japan’s treaties with other countries like Indonesia, China and Myanmar after World War II, which used the word “reparations” to address the damage and suffering caused by Japan, the Claims Agreement was silent on any wrongdoing and, therefore, meant only to address the settlement of credit and debt relations, such as insurance and deposits. The commission added that, because the Japanese government refused to recognize any legal obligation to provide reparations for forced labor, the Korean government pursued political compensation based on the “historical fact of losses from affliction.”

Commentators have explained that the two governments at the time negotiated the Claims Agreement to be ambiguous on key issues — including how to characterize Japan’s colonization of Korea (legal versus illegal), which claims were being settled (government versus individual claims, torts against humanity) and what the money was for (economic assistance versus reparations) — so that the two sides could normalize relations, secure economic benefits and “go back to their people and tell two different stories.” The commission also underscored that the South Korean government had a moral responsibility to use a considerable portion of the Japanese funds it received from the agreement to compensate the forced labor victims, but that the compensation payments made between 1975 and 1977 were inadequate. This finding led the Roh administration to enact additional compensation legislation in 2007.

The reassessment of the 1965 agreement ultimately led to a major shift in South Korean court decisions. In landmark rulings in May 2012, the South Korean Supreme Court decided that the individual claims against Nippon Steel Corporation (and the claims of another group of plaintiffs against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) were not extinguished by the agreement. Underscoring that Japan’s colonization of Korea was illegal, the court rejected the lower court’s deference to Japanese verdicts because it would violate South Korea’s constitution. The court also drew on the commission’s findings to hold that the agreement’s failure to acknowledge the illegality of Japanese colonialism meant that it was merely a “political agreement” to settle economic and debt relations between the two countries, rather than compensation for Japan’s illegal occupation. Lastly, the court held that the statute of limitations for raising claims had not expired due to legal obstacles that prevented the plaintiffs from exercising their right to raise claims. After the cases were remanded, the lower courts ordered the two Japanese companies to compensate the South Korean plaintiffs.

In late 2018, the South Korean Supreme Court affirmed the damages awards and reaffirmed its previous ruling that the agreement did not extinguish individuals’ claims for reparations. The court stated that Article I, which described the Japanese government’s payment, said nothing about the specific purpose of the payment other than being “conducive to the economic development of the Republic of Korea,” and had no relation to the claims described under Article II. Even Japan’s position at the time, the court noted, was that the payment was only for economic assistance and not reparations. Most importantly, the court characterized the plaintiffs’ claims as seeking compensation for emotional suffering caused by the Japanese corporation’s unlawful acts rather than for lost wages to ensure that the claims fell out of the agreement’s scope concerning “property, rights and interests.” Using this logic, some scholars have also argued that the eight items raised by South Korean negotiators in 1965 also did not include mental harm.

The 2018 court decision quickly created a fissure in bilateral ties. In July 2019, Tokyo imposed tighter export controls on chemicals used by South Korean manufacturers to produce semiconductors and removed South Korea from its “white list” of preferred trading partners. Although Japan attributed this move to security concerns based on South Korea’s “inadequate management” of the chemicals, then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe admitted that the 2018 court decision was the primary reason. South Korea countered with its own measures, including dropping Japan from its white list, initiating dispute resolution proceedings at the World Trade Organization over the export controls and threatening termination of the bilateral General Security of Military Information Agreement.

Since then, South Korean lower courts have muddied the waters by producing contradictory rulings (legal precedents are not binding in South Korea’s civil law judicial system). In three cases last year, the Seoul Central District Court decided against South Korean laborers. That same year, however, district courts in Daejeon and Daegu approved the sale of Mitsubishi and Nippon Steel assets to allow South Korean victims to collect. In April 2022, the Daejeon District Court ordered the sale of a Mitsubishi patent to compensate a forced labor victim. With the South Korean Supreme Court’s dismissals of Mitsubishi’s appeals in the first Daejeon case in September and December 2021 and the likelihood that the Seoul Central District Court’s decisions will be reversed based on the 2018 decision, the Japanese side appears to be running out of legal recourses.

The Way Ahead

There are several potential paths forward regarding the forced labor claims, though none are encouraging. The Japanese companies have already rejected the first option of abiding by the South Korean Supreme Court’s decisions and compensating the victims. With many similar lawsuits pending in South Korea, complying with the courts’ decisions could mean hundreds of millions of dollars in additional liabilities for Japanese companies. More important, this move would be tantamount to admitting that Japan’s colonization of Korea was illegal.

A second path would uphold Japan’s position but require a political, legislative or judicial act by South Korea that undermines or supersedes its supreme court’s rulings. This type of move is possible but would be unpopular in South Korea and kick the victims’ rights can down the road. In addition, if a judicial act is perceived as politically driven — for example, former South Korean Supreme Court Chief Justice Yang Sung-tae was arrested in 2019 on charges of delaying a final verdict on the laborer cases — it could diminish the integrity of South Korea’s judicial independence.

In 2019, then-South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s government sought a third path that could satisfy Japan’s concerns while also not undermining the 2018 court rulings. It proposed establishing a joint fund managed by the two governments using voluntary contributions from South Korean and Japanese companies to compensate the victims. This fund would resemble the mechanism that Germany, amid a wave of lawsuits in U.S. courts against German companies, devised in 2000 to compensate former Nazi-era forced laborers. Japan rejected Moon’s proposal arguing that all claims had already been settled. It also felt chagrined by Moon’s dismantling of a similar fund created in 2015 to address the concerns of Korean “comfort women” — women who were forced to work in brothels run by the Japanese military before and during World War II. The Yoon administration could also propose a joint fund, but it will need to ensure the Japanese government’s buy-in and that victims’ concerns are addressed.

A fourth potential path is arbitration. Article III of the Claims Agreement calls for any disputes that cannot be settled through diplomatic channels to be referred to an arbitration board. Japan initially sought arbitration in 2019, but South Korea demurred as it tried to exhaust diplomatic solutions that would address the victims’ claims with greater certainty. Today, with no diplomatic solution in sight, the two sides could still choose to pursue arbitration as a legally binding option. However, the risk of a negative ruling remains for both sides. Another legal recourse would be to pursue a decision by the International Court of Justice, but South Korea would first need to accept the court’s jurisdiction.

The most controversial, and least likely, option would be to revise the Claims Agreement. This path would be a nonstarter for Japan, and perhaps South Korea as well, but it could offer potential benefits. Rather than cede control of the agreement’s interpretation to arbitration boards or domestic judicial systems, this approach would afford both governments equal agency and responsibility to directly confront and resolve the 1965 agreement’s fundamental flaws — for some, ensuring that the bilateral relationship’s “first button” finally finds its correct place.

Absent any of the five measures above, the situation will worsen. South Korean courts will allow Japanese companies’ assets to be seized and liquidated; the Japanese government will retaliate, prompting South Korean countermeasures; bilateral tensions will fester; and the Northeast Asian link in the latticework of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy will grow weaker.

The U.S. Role

U.S. leadership can help avoid this outcome. Strengthening U.S. alliances in the region is one of the Biden administration’s highest foreign policy priorities. Washington will want to avoid the appearance of meddling or favoritism, but the history of South Korea-Japan relations shows that the United States has always weighed in discreetly, and sometimes openly, with considerable influence. In 2014, then U.S. President Barack Obama called the “comfort women” tragedy a “terrible, egregious violation of human rights” and encouraged Japan to recognize the past “honestly and fairly.” The current environment may be amenable to similar prodding since both Yoon and Kishida will be more flexible on this issue than their predecessors.

When Biden meets the two leaders, improving South Korea-Japan relations must be one of the top agenda items. The fund proposal may be the best option because it allows both governments to influence the outcome and, if designed well, the victims’ concerns to be settled. A sustainable solution requires addressing the victims’ claims and grievances in a fundamental and comprehensive way.

Sang-ok Park is a former justice on the South Korean Supreme Court.