How to Address the Racism at the Heart of Japan-South Korea Tensions

U.S. politicians, businesses and media should examine their role and help tackle anti-Korean prejudice.

Anti-Korean racism is at the heart of historic and unresolved tensions between Japan and South Korea. It will be near impossible to resolve disputes like the comfort women issue without addressing this racism. This is because the difficulty in reaching a consensus on the Japanese side often derives from the underlying tendency among many Japanese to view Koreans as “inferior” and “untrustworthy.” U.S. actors, including officials, businesses and academics, should understand the consequences of the important role they have played in perpetuating such prejudice and help right this wrong.

A History of Anti-Korean Racism

In Japan, racism is a powerful underlying social force that shapes many issues, including the government’s general orientation. It has many targets, including Okinawans, Ainu, Chinese and foreign laborers, but anti-Korean racism has been particularly salient over the past two decades.

Anti-Korean racism in contemporary Japan has its origin in Japanese imperialism, and it remains imperial in tone today. Like other empires, Japan expanded its territories in the late 19th century based on the assumption that it was superior to the colonized people and that they needed Japan’s help to free themselves from their own “backwardness” or from other empires.

The imperial-racist assumption became blatantly obvious in 1923 after the Great Kanto Earthquake — rumors spread that Koreans were poisoning wells and setting fires, and Japanese mobs massacred and lynched Koreans and other minorities who were mistaken as Koreans. The Japanese police and army were involved in both the instigations and violence.

The Japanese empire also had a uniquely strong assimilationist orientation. Especially during the war years (1937-45), it undertook a large-scale ethnic conversion of Koreans, Taiwanese and others, seeking to reprogram them to become “ideal Japanese.” This wartime Japanization effort left at least two major legacies in postwar Japan. First, conservative Japanese leaders revived a view of Koreans and Korea as backward, uncivilized and dangerous. Second, many Koreans, especially those remaining in Japan (whose descendants are called Zainichi Koreans), strongly desired to undo Japanization and to regain ethnic pride and autonomy. In their pursuit of Korean liberation, a large number of Koreans in Japan built hundreds of schools and organized themselves under a mass organization, the League of Koreans.

The United States: An Unwitting Accomplice

The United States has been — unwittingly — a key accomplice in perpetuating postwar anti-Korean prejudice in Japan. The U.S. occupation of Japan (1945-52) naively inherited the perceptions of Japanese policymakers, defining Koreans as undesirable criminals and threats to society.

The U.S. officers’ image of Koreans also came from the southern half of Korea, which itself was under U.S. military occupation. Across the post-liberation Korean peninsula, the desire for an independent nation free from outside powers was strong, and many local leaders created “people’s committees,” which soon leaned politically to the left, to pursue self-rule. To the U.S. officers, these movements appeared to pose serious communist threats. In their Cold War mapping, people’s committees in South Korea, the North Korean regime and Korean activists in Japan constituted an interlinked security problem. This mindset quickly turned tensions between the South Korean regime and its people into massive violence, as seen in massacres conducted by the police and rightwing groups in the name of putting down riots and communists — for instance, the Autumn Uprising (1946) and the Jeju Massacre (1948 to 1949). U.S. and Japanese authorities also cracked down violently on Korean schools and the League of Koreans in 1948 and 1949. These actions were part of their regionwide battle against “communists” and a prelude to the Korean War.

Anti-Korean racism in postwar Japan not only survived but increased after the U.S. occupation ended. In 1952, after the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Japan returned to international society as a democratic, peace-loving nation, presumably the opposite of what it had been before August 1945. But the treaty failed spectacularly to settle the issues of Japanese imperial aggressions in Asia — or of any imperialisms. Through that global neglect of de-imperialization, Japan-South Korea negotiations for diplomatic normalization came to a deadlock. Although it had no formal relations with either of the two Koreas, Japan legislated the exclusion of the former colonial subjects living in Japan by stripping them of Japanese nationality, purportedly based on the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Koreans in Japan thus became stateless.

From the 1960s onward, the United States continued to inadvertently encourage the Japanese imperial-racist view of Koreans. During the negotiations over the South Korea-Japan normalization treaty, which the United States powerfully facilitated, the Japanese side strongly asserted that its colonial rule had helped an “underdeveloped” Korea — and it was not alone in holding that view. John F. Dulles, a U.S. diplomat and the main architect of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, explained Western colonialism using the same vocabulary. Edwin O. Reischauer, a prominent scholar of Japan and the U.S. ambassador to Japan who pushed for the 1965 normalization treaty, introduced the so-called modernization theory to Japanese scholars in 1960. This “modernization” paradigm valorized economic development and positioned postwar Japan as an example that other Asian nations should follow. U.S. leaders wanted to see that worldview spread to legitimize their own developmental schemes abroad and overcome Marxist appeals. But it also provided a basis for their Japanese counterparts to defend the colonial rule of Korea. This attitude persisted in popular history writings and the government’s stance for the next decades.

A New Anti-Koreanism Emerges

In the 2000s, a new type of anti-Koreanism emerged in Japan. Many elements contributed to it, including the largely unregulated internet, a sense of disfranchisement due to long-term economic stagnation, South Korea’s rise as a new economic giant and North Korea’s aggressiveness — expressed through repeated missile launches, its nuclear weapon development and the late Kim Jong-il’s admission of the abductions of Japanese citizens. Also, the Shinzo Abe administrations (2006-07 and 2012-20), which espoused historical revisionism, fanned the flames of anti-Korean sentiment to rally mass support. Abe’s followers celebrated his censorship of the media and school textbooks, turning historical denialism of “comfort women” into mainstream thinking.

The Koreas and Koreans, particularly Zainichi Koreans, became the target of renewed racism. Hate speech spread and Korean school students were harassed and traumatized. In 2021, a man set fire to an office of an ethnic Korean organization, a Korean school and residences in a historically Korean district known as Utoro.

In Japan’s 2022 national election, the founder of a far-right anti-Korean group ran for office, shouting slurs against Koreans during his campaign. The fact that many people in Japan were keen to find out whether the suspect in Abe’s July 2022 assassination was a Zainichi Korean (he is not) shows how intense the tensions have become.

The Present U.S. Role

The United States still plays an important part in this picture. Prewar and postwar imperialist Japanese politicians often counted on approval from authoritative U.S. voices, and that dynamic has not changed. Far-right Japanese nationalists have been working closely with several white American figures who reinforce their worldview by preaching Japan’s superiority over Korea. They also consider the United States the “main battleground” in their efforts to spread historical denialism. In fact, they recently found a perfect ally in a professor at Harvard Law School, who calls the story of comfort women “pure fiction” and argues that leaders of Zainichi Koreans and other minorities promote the discrimination against their groups to personally profit from government subsidies, based on dubious interpretations of history and data.

Most U.S. officials — occupation officers, diplomats, scholars and politicians — probably had no intention of harming the South Korea-Japan relationship or perpetuating Japanese racism (with the exception of recent historical denialists). If anything, the United States has tried to function as an arbiter between the two sides. But the result of U.S. attempts to pursue its own strategic interests, often through raw violence, legal power or academic authority, have ended up buttressing Japanese racism in various ways. Because such racist behavior has become an important source of support for rightwing Japanese politicians these days, there is little incentive for them to respect South Korean leaders and civic groups or to commit to conciliatory agreements. It is time to end that cycle and allow the anti-racist voices in Japan to produce new political momentum toward South Korea-Japan reconciliation.

In light of the United States’ unfortunate history as a pivotal — albeit unintentional — legitimizer of Japanese racism, there are many things U.S. politicians, businesses and media can do to improve the situation. They can start by being mindful of this racist strain of thinking in Japan and having a zero-tolerance policy in their dealings with their Japanese counterparts.

Recommendations to Address Japanese Racism

We tend to think of Korean-Japanese tensions in terms of topic areas, such as Japan’s recurring historical denialism, the territorial dispute and the failure of diplomatic arrangements. But these tensions are largely manifestations of racism, not the cause of it, and they will persist as long as racism itself remains unaddressed. The following recommendations would help address this prejudice.

Tackle racism transnationally.

The rise of racism in Japan is not an isolated affair, and has grown hand in hand with racism in the United States and around the world. Some politicians, scholars, journalists and activists in Japan have opposed anti-Korean racism for a long time and are frequently under attack, partially because they are often isolated from larger movements. Developing anti-racist coalitions and promoting public discussions with them can give them legitimacy and send a message to Japanese society.

Demand that Japanese companies commit to stopping racism.

U.S. companies should reiterate their zero-tolerance policies in their dealings with Japanese companies — specifically regarding hate speech, harassment or financial support for organizations that spread hateful information about minorities. U.S. businesses can encourage their employees and customers to report cases of racism; educate themselves about far-right and racist companies, such as APA Hotels and DHC (and there are many more); and make it known that they will avoid working with Japanese companies that tolerate or espouse racist practices.

Avoid expedient diplomatic solutions.

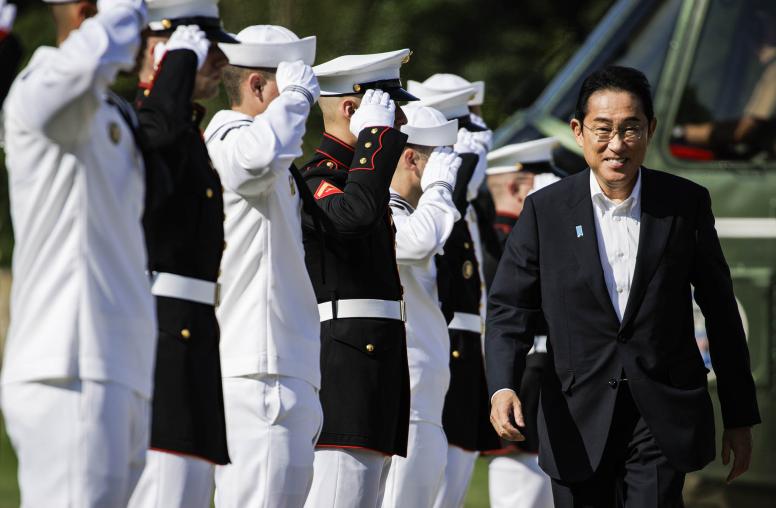

Agreements fail for a variety of reasons, but one reason is the failure to tackle anti-Korean racism in Japan. The 2015 Park-Abe “comfort women” agreement was a case in point. Also, since Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has been eager to obtain support from other governments for resolving the issue of Japanese civilians abducted by North Korea, these governments should recognize that this issue has become a rallying point for anti-Korean racists. Even though resolution of the abductee issue is urgently needed, the main “civic” group representing the abductee families has veered to the far right, and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party leaders have been using the issue as a politically unifying symbol while avoiding serious negotiations. For this reason, U.S. officials and politicians should be careful about appearing at their events or in their publications. Instead, they should make statements independently and suggest that the Japanese government invest in more effective and practical negotiations with North Korea.

Don’t sacrifice democracy for national security goals.

U.S. policymakers tend to overlook problems in the domestic procedure in Japan, especially when doing so helps to secure Japan’s active commitment to regional defense. The Abe administration, for example, often suppressed media freedom, democratic legislative procedures, political accountability and academic autonomy. In the long run, however, looking the other way on poor democratic norms will help increase xenophobia and racism and heighten regional tensions.

Protect scholars and academic freedom in the United States.

U.S.-based historians working on East Asia are tackling major cases of historical denialism to ensure academic integrity. Some historians are threatened and harassed by Japanese right-wingers as a result. U.S. officials and academic institutions should protect researchers from such threats and harassment.

Sayaka Chatani is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the National University of Singapore.