Middle East Peace: What can we Learn from Camp David 40 Years Later?

Camp David’s ultimate legacy will depend on how its vision for a broader regional peace is translated to reality.

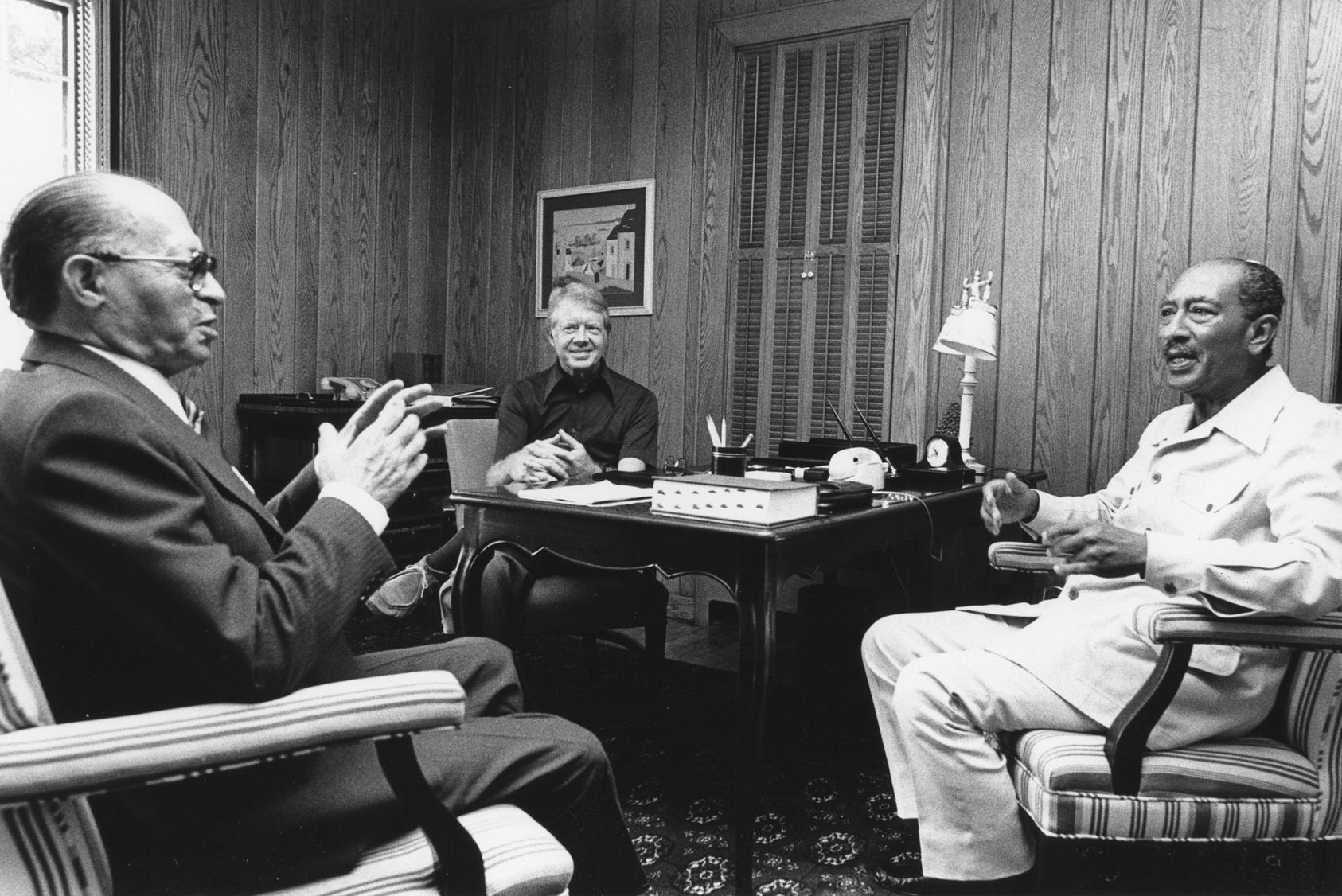

March 26 marks the 40th anniversary of the signing ceremony of the Egypt-Israel peace treaty that resulted from the Camp David Accords. Negotiated by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and U.S. President Jimmy Carter, the treaty has been a cornerstone of regional security and U.S. strategy in the Middle East. The Camp David Accords’ first document paved the way for the 1993 Oslo Accords between Israelis and Palestinians, which in turn opened the door to the 1994 treaty between Israel and Jordan. USIP’s Robert Barron, Lucy Kurtzer-Ellenbogen, and Michael Yaffe examine the legacy of Camp David and what, if any, lessons can be learned that could help advance the Israeli-Palestinian peace process today.

Forty years later, how have the Camp David Accords impacted the Middle East and regional peace?

Camp David was a landmark moment in Middle East politics. In September 1978, Israel and Egypt had been in conflict for 30 years, with the threat of yet another disastrous war looming over the leadership and the publics. Forty years after the treaty, the relationship between Egypt and Israel—while certainly limited—is stable, mutually beneficial and peaceful. Camp David also set important precedents in how Middle East peace is negotiated and how Arab and Israeli interests should be accounted for in a peace process. Sadat and Begin were generally able to recognize their mutual and shared interest in ending hostilities. They were also able to build mechanisms to ensure the stability of the treaty—most importantly in security arrangements and oversight mechanisms.

Important to remember in assessing outcomes, however, is that Camp David consisted of two letters—one describing a regional peace and solution for the Palestinians and the other outlining Egyptian-Israeli peace. For decades now, diplomats have been seeking a formula for an acceptable compromise between the Israelis and Palestinians, which would fulfill all the aspirations of Camp David.

The unrealized vision of that first document, alongside the successes of the second, highlights the important differences between the two conflicts and the limitations generated by a stagnant Israeli-Palestinian peace process. While both Egypt and Jordan have formal peace treaties with Israel, because of the lack of a solution for the Palestinians, relations are limited, cold, and mostly at the elite-level. Looking ahead, the full measure of Camp David’s legacy will depend on how its vision for a broader regional peace—with a just solution for the Palestinians—is translated to reality.

In a recent article for the Cairo Review of Global Affairs, you wrote, “The fundamental differences between the Israeli–Egyptian conflict and that between Israel and the Palestinians has limited Camp David’s applicability to the latter.” What are those fundamental differences? What, if any, lessons can be learned that could help advance the Israeli-Palestinian peace process today?

In the article, we look at the reasons the Camp David Accords were successfully negotiated, and why the agreement has held. Much of the treaty’s success is in its details—most notably the security coordination and mechanisms the parties defined—but at least as important is the context of Egypt-Israel relations. The Israeli-Egyptian treaty addresses security as a matter of military disengagement and nonbelligerency. Essentially, Sadat and Begin knew where to draw the border between these two established states and ensure each stayed behind it.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is rooted in many more issues than the Israeli-Egyptian conflict. Both parties’ sense of nationhood is tied to the same land and the claims of both parties are much more zero-sum. With or without a negotiated solution to the conflict, the futures of these two peoples will be closely intertwined.

The past 30 years of diplomacy demonstrate how difficult it is to find mutually acceptable middle ground on the complicated and emotional final status issues at the root of the conflict. The Oslo process was an example of an effort to reach a peace situated in security, but ultimately fell short, in no small measure, because of the inability to fully address the full-sweep of final status issues. One lesson from recent years is that the longer the conflict continues, the more difficult it has become to find solutions that address Palestinian aspirations for statehood, borders, return of refugees and the status of Jerusalem, among other things. One of the thorniest final status issue will be finding a formula that meets both parties’ security needs.

Two other important lessons are less tangible. Camp David required remarkable leadership from Sadat, Begin and Carter. Sadat took enormous political risks—which ultimately cost him his life—as he engaged in negotiations with Israel. Begin was no peacenik yet pushed through his skepticism and ideology to achieve an agreement. And despite a number of challenges and early failures, Carter found a way to play the role of credible intermediary and broker. Camp David is a dramatic story of diplomacy and leadership.

Finally, Camp David is also representative of how dynamic international politics and peacemaking can be. In the early-mid 1970s, no one would have predicted an Israeli-Egyptian peace before the end of the decade. The 1973 War had bloodied both parties and was used by Sadat and the Arabs as a rhetorical tool. But within a matter of months, Sadat stood on the Knesset (Israel’s parliament) floor, an agreement was negotiated at Camp David, and a peace treaty—which has held for 40 years—was signed. Despite decades of hostility before the agreement, changes in leadership, and occasional points of tension since, the public has adapted to a peace that serves its interests.

The Multilateral Force and Observers (MFO) mechanism has been one of the major successes of the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty. What has made this mechanism so resilient? Is there an MFO-style arrangement that could work in the Israeli-Palestinian context?

The Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) is the institution created by the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty to supervise the implementation of the security provisions of the agreement and to prevent violations. It was designed by the Israelis and Egyptians for their particular security situation and is limited in scope to the Sinai Peninsula. The success of the MFO structure rests on several mutually reinforcing pillars, both structural and substantive. Its mandate is specific and unambiguous. Both parties feel a sense of ownership and investment in the longevity and stability of the peace they negotiated. Steady U.S. leadership and support have been a crucial linchpin. All of these are buttressed by an effective command structure and streamlined decision-making and communication channels. The net result is a mechanism respected by both sides as reliable and professional, and in which both see the value in sustaining.

Not surprisingly, the MFO’s success has frequently prompted this question of its applicability to the Israeli-Palestinian context. In the wake of the failed second Camp David summit between Israelis and Palestinians in July 2000, there was significant and detailed examination of its potential. However, in the current context, when the fate of the two-state solution is uncertain, the viability of such a formula is difficult to assess. The operating assumptions for considering an MFO model for Israelis and Palestinians mirror the pillars of the Egyptian-Israeli treaty. These include a two-state solution in which all major claims are resolved, all borders are final, Israeli forces eventually withdraw from the West Bank, and both sides accept international force presence and assistance.

Getting to this formula will not be an easy lift. Israel, despite the success of the MFO, and grounded in experience elsewhere, remains cynical about the effectiveness of international forces in guarding against threats to its territory and is not inclined to entrust its security to anyone else. Palestinians have shown a willingness to accept a third-party presence in a future Palestinian state but regard the prospect as an interim measure. The particular complexities and asymmetries of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict relative to what existed between Israel and Egypt are likely to make squaring these circles an even heavier lift than what was improbably accomplished at Camp David in 1978. That said, the latter offers lessons in the power of leadership and political will to unlock the seemingly intractable and open the door to the kind of agreement that could be sustained and strengthened by an MFO-style arrangement.

Sadat’s groundbreaking trip to Jerusalem and speech before the Israeli Knesset in 1977 was a “momentous first step” in the Camp David process. What similar measures could be taken today by Arab and Israeli leaders to advance the prospects for peace?

President Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem was a psychological game changer which, alongside the agreement that ensued, set lasting precedent and expectations for Israeli-Palestinian and Arab-Israeli peacemaking. Today, despite what seems to be gradually improving ties between certain Arab states and Israel, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains a ceiling to full and formalized Arab-Israeli peace.

Successfully addressing this issue will require the parties to overcome the distinct challenges of a conflict in which both parties’ national identity is wrapped up in claims to the same land. Both Israelis’ and Palestinians’ sense of existential security relies on acceptance, recognition of legitimacy, and a definition of a border. It is almost inevitable, therefore, that bold leadership, exemplified by Sadat-style gestures and the reciprocating courage of Begin will be required to open the door to a negotiated peace. Within that framework, the real game-changing gestures must come from Israeli and Palestinian leaders.

If the chasm of trust between the parties today seems deeper than ever, the good news is that public opinion is dynamic. Camp David itself serves as an example of how readily public support for peace can be rapidly enhanced when the prospect becomes real. Polling in the Israeli-Palestinian context over time has likewise strongly indicated that when each side believes the other is acting in good faith to pursue peace, support for reaching a negotiated agreement goes up. This should ultimately serve as an incentive that opens the door to Israeli, Palestinian, and third-party leaders willing to seize the opportunity and confront the challenges of the conflict with the pragmatism, empathy, courage, and creativity that were hallmarks of Camp David.