The Peacebuilder’s Field Guide to Protest Movements

Protest movements around the world scored major victories in 2015. But if we want to see real change, international donors need to stop fretting and lend a hand.

As we settle into 2016, it might appear as though the defining story of the previous year was the rise and stretching reach of extremist violence. A string of deadly terrorist attacks in Beirut, Paris, San Bernardino, the Malian capital Bamako, and Jakarta left the impression that the large-scale chaos of the Islamic State has pollinated smaller pockets of havoc the world over. And though it’s fair to think that — as these are the stories that dominated headlines for months — that isn’t the whole story. The flurry surrounding this horrific violence has obscured an alternative narrative: that nonviolent citizen movements across the world scored sweeping and transformative victories in 2015. And, as protests are on the rise, these movements could play an increasingly important role in cutting the roots of violent extremism.

In Iraq last summer, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi was forced to launch a corruption probe and overhaul the government after unprecedented, sustained protests over electricity cuts and shoddy service delivery by thousands of citizens in many parts of Iraq — demonstrations that, at first glance, had little to do with the Islamic State’s terrorizing of the country’s north. In September, a broad-based movement in Guatemala, backed by a United Nations anti-corruption commission, forced a kleptocratic president and his entourage from power without bloodshed. In these cases, popular movements used nonviolent tactics of disruption — including strikes, boycotts, and demonstrations — to shake up the status quo and challenge symbols of corruption and oppression.

It is remarkable that people power took root in countries that have endured years — even decades — of violent conflict. The challenge for 2016 will be to build on these nonviolent successes and help them lead to institutional changes. The question is: How many of these protest movements can translate upheaval into real, sustainable peace? To increase their chances, they’re going to need more help from an international donor community that has historically shied away from the tumult of resistance movements.

The trend is an encouraging one — similar events in other countries, even tumultuous ones, have won real sustainable peace. The difficulties of moving from protests to peaceful politics have plagued countries ranging from Egypt to Thailand, where repeated “regime changes” have failed to consolidate democracy. Yet, research shows that societies that experience major nonviolent campaigns, including those that fail (think the 2007 monk-led Saffron Revolution in Myanmar), are almost 10 times more likely to democratize and avoid civil war than those that experience armed campaigns. Successes, like that of the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize this past October, can be used as guides for converting upheaval to positive change.

So why doesn’t this symbiosis of nonviolent resistance, which involves escalating conflict nonviolently, and peace building, which involves de-escalating conflict, occur more often? One reason is that populations challenging their governments make the foreign donors that most often support peace-building techniques more than a little nervous. After all, movements and their outcomes are unpredictable, as was seen with the 2011 Arab Spring. Confrontational activity can sometimes lead to violence. Nonviolent direct action, furthermore, often happens outside of normal institutions and processes that donors are more familiar with.

The instinct to stay away is the wrong one, however. Donors must realize more often that they can help civil society acquire the skills to channel nonviolent direct action tactics into sustainable movement building and institutional reforms. This does not mean that outside actors, especially governments, should encourage protests — they shouldn’t. But if donor agencies and private foundations that support peace building with training and small grants in places like Iraq, Guatemala, Uganda, and Myanmar could find ways to bring these nonviolent skill sets closer together, it would go a long way toward preventing and mitigating violent conflict globally.

* * *

At first glance, civil resistance and peace building might seem at odds: Boycotts, strikes, civil disobedience, and street theater — just a few of the hundreds of tactics involved in nonviolent resistance — can be viewed as unhelpfully escalating conflict and creating societal polarization. On the other hand, relying on dialogue in cases where there are profound power asymmetries and structural injustices can be seen as an exercise in futility.

The thinking behind the two isn’t as far apart as it might seem, though. Both nonviolent resistance and peace-building experts acknowledge that conflict is positive, even necessary, to bring about salutary societal changes; both communities oppose violent conflict, regarding it as ineffective at resolving conflicts and tackling their root causes. Whereas nonviolent resistance employs sometimes confrontational, direct action tactics to put pressure on power holders and challenge policies or practices, peace building generally relies on dialogue, facilitation, negotiation, and creative problem solving to de-escalate conflicts and achieve mutually acceptable solutions.

Experts from Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation concluded that when used jointly in the same conflict, “negotiation and nonviolent action not only share commonalities, but often have synergistic qualities.” In his famous 1963 “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. responded to criticisms that the sometimes disruptive tactics of the U.S. civil rights movement were “unwise and untimely” and that he should be seeking dialogue instead:

‘Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches, and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?’ You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.

In conflicts where power is uneven and discrimination is institutionalized (as in most intra-state conflicts), those power dynamics need to shift in order for peace to have a chance. It is exceedingly hard to change these internal dynamics through external military action, as Afghanistan and Iraq have clearly shown. Organized nonviolent action by those living under oppression has a much greater chance of tipping the balance and achieving longer-term peace and stability.

* * *

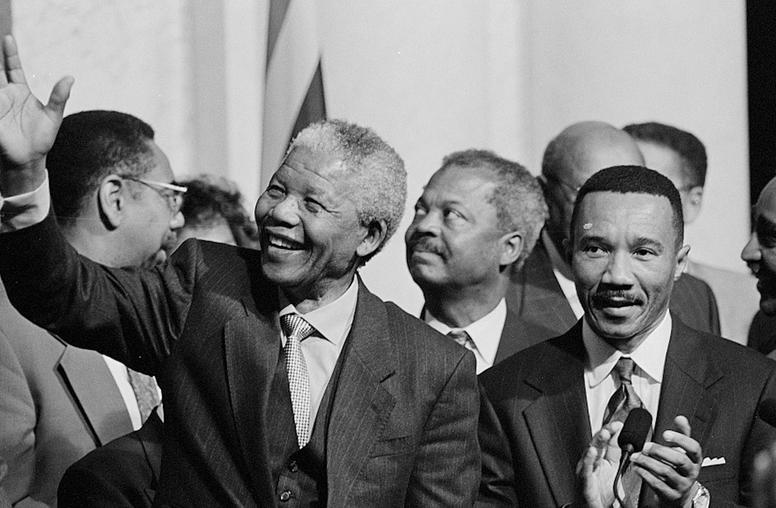

History is full of models for how this might be done. It is hard to imagine F. W. de Klerk agreeing to negotiate with Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress in 1990, absent the powerful boycott campaign led by the United Democratic Front and civic groups inside South Africa and divestment and sanctions coming from the outside. Polish Solidarity, a labor movement that challenged communist dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s, masterfully combined nonviolent mass action with negotiations: The Gdansk shipyard strike in 1980 put tremendous economic pressure on the Wojciech Jaruzelski regime, which years later yielded to the movement and its leader, Lech Walesa, during negotiations. In the nonviolent resistance campaign led by the Serbian youth movement, Otpor, in 2000, the students’ negotiations with security forces were critical to prompting defections and forcing Slobodan Milosevic to step down.

There have been historical failures as well, which show how promising movements have missed the mark. The courageous protests led by Chinese students in Tiananmen Square in 1989 prompted Deng Xiaoping’s government to agree to free student associations and greater media freedoms. However, the student movement was divided about whether to negotiate with the government, and so they rejected concessions, thereby strengthening the hand of government hard-liners. On June 3 and 4, after the government sent tens of thousands of armed troops and hundreds of military vehicles to the city center, Chinese and Western witnesses and human rights monitors estimate that anywhere from several hundred to more than 2,000 protestors were massacred.

Tunisia’s transition from dictatorship to fragile democracy is one of the best recent examples of what can happen when negotiations are backed by the nonviolent force of organized citizen action, offering relevant lessons for countries where corruption and weak (or noninclusive) institutions continue to fuel violence, insurgency, and extremism.

After fruit-seller Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation, spontaneous youth-led street protests quickly found organized channels through the labor and trade unions, which mobilized hundreds of thousands of workers to engage in boycotts, demonstrations, and work stoppages. A civic coalition — the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, comprising the Tunisian General Labor Union; the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade, and Handicrafts; the Tunisian Human Rights League; and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers — orchestrated a national dialogue in 2013 and mediated a democratic “road map” after the Jasmine Revolution ousted then-President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, and at a time when social unrest threatened to escalate into civil war. They put aside traditional differences to unite and nudge the political leaders to agree to democratic rules of the road and persuaded the Ennahda-led government to relinquish power to a caretaker, which paved the way for new elections held in the fall of 2014 — the first time an Islamist-led government created through the Arab Spring willingly yielded power. The political deal stuck because organized labor and professional groups could back the Quartet’s peace building with nonviolent mass action.

In order to expand the repertoire of nonviolent responses to conflicts around the world, leaders in the civil resistance, community organizing, and peace-building fields should join forces. Whether the issue is preventing electoral violence, countering violent extremism, or addressing state fragility, the menu of non-military response options would be vastly enriched if these tools and approaches were brought together.

Collaboration starts by acknowledging that skills in nonviolent organizing and direct action designed to shake up an unjust status quo need to be backed by activities focused on dialogue and negotiation to build bridges between divided communities and achieve win-win solutions. Global associations that include nongovernmental organizations that support both nonviolent resistance and traditional peace-building activities, like the Alliance for Peacebuilding, are particularly well positioned to advance leadership and collaboration in the field.

For governmental donors like USAID as well as private foundations, this means devising interventions with civil society that support both forms of nonviolent activities. This requires caution and nuance, as the last thing donors should do is provide material or other forms of support that could endanger the safety or legitimacy of local civic actors or the movements they lead. U.S. President Barack Obama’s Stand With Civil Society initiative, and his 2014 presidential memorandum calling on all U.S. government agencies to step up their interaction with civil society overseas and to push back on government attempts to restrict civic space, offers a useful policy umbrella to bring these perspectives together.

As experts from Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation noted in a 2008 symposium on negotiation and strategic nonviolent action, “Negotiation and nonviolent action are arguably the two best methods humanity has developed for engaging in peaceful conflict resolution. Both are remarkably effective alternatives to war and can be viewed as distinct activities within the same larger process.” Helping local activists and peacebuilders skillfully and strategically use these nonviolent tools to transform conflicts away from violence and toward a just peace should be a priority for donors and outside supporters in 2016. If they can pull it off, the world might look back next January at a much more peaceful year.

Reposted with permission from ForeignPolicy.com, Source: “The Peacebuilder’s Field Guide to Protest Movements"