The Practice of International Criminal Tribunals and their Relevance to Military Commissions in Light of Hamdan v Rumsfeld

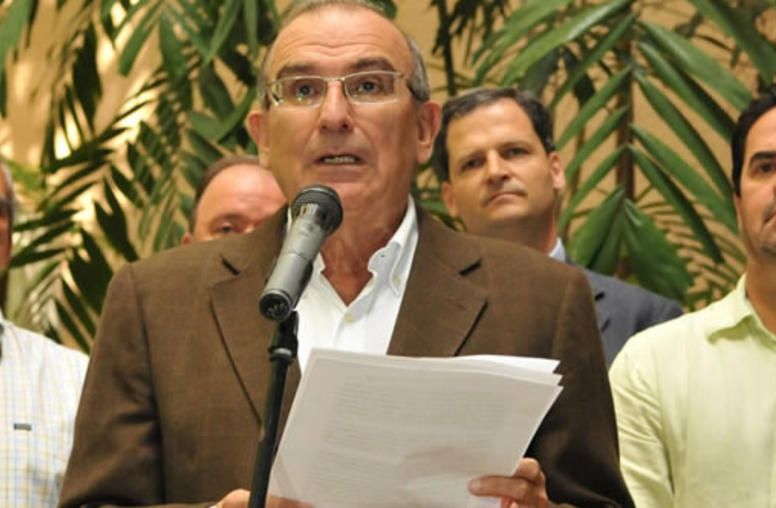

Gerald Gahima testified before the House Armed Services Committee on protecting fair trial rights, witnesses, and national security in international criminal tribunals.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee for inviting me to speak this afternoon. I am honored to be among such distinguished company.

I would at the outset wish to take the opportunity to clarify that I am testifying in my personal capacity and that the views I will express are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace.

Mr. Chairman, I have been intimately involved with prosecutions of the crimes that were committed during the Bosnia and Rwanda conflicts of the early 1990's. I was for some years responsible for both Rwanda's own genocide investigations and prosecutions and support to the work of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (the ICTR). I worked with law enforcement of states such as Belgium, Switzerland, and Canada in their efforts to investigate crimes arising from the Rwanda genocide. I have also been involved in the establishment of the War Crimes Chamber of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

National courts and international criminal tribunals responsible for the trial of those who committed violations of international humanitarian and human rights law (during the Rwanda and Bosnia conflicts) have grappled with the complex problem of safeguarding the rights of defendants to fair trials. In war crimes trials, as in ordinary criminal cases, the defendant's right to a fair trial must be balanced against the rights of the victims. In the age of crimes of terrorism on a global scale, fair trial guarantees must be considered in the light of national security considerations as well.

Many of the evidentiary and security challenges that the U.S. legal system faces as it seeks to establish harmony between the requirements to ensure compliance with international fair trial norms and the exigencies of waging a war on terror have been the subject of war crimes litigation before other national courts as well as international tribunals. I would like to discuss some issues that have confronted both the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (the ICTR) and its sister tribunal, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (the ICTY). Their experiences may be of particular relevance to efforts of the United States to craft appropriate mechanisms and procedures for ensuring both due process in trials of terror suspects and for dealing effectively with existing and future terrorists threats. The question which my testimony seeks to address is whether the experience of war crimes prosecutions over the last ten years or so has any lessons for America as to how it may seek to balance obligations to ensure compliance with fair trial guarantees, to protect witnesses, and to safeguard national security.

In the remainder of my testimony, I will address the following: the fair trial rights of defendants; the use of hearsay evidence and evidence obtained from foreign states; procedures developed to respect the national security concerns of cooperating states; and ways to protect victims and witnesses. The International Criminal Tribunals have addressed these issues in the quest to balance the rights and concerns of all parties to a trial.

Protecting Defendants' Rights to Fair Trials

The right to a fair trial is a fundamental norm of international human rights law. This right is enshrined in several human rights treaties which the United States has ratified, especially the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The substance of the provisions of the ICCPR appears in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, whose provisions are for the most part considered to be declarative of customary international law. The right to a fair trial is considered to begin not upon the formal lodging of the charge, but rather on the date on which state's activities substantially affect the situation of the person concerned. Fair trial guarantees must be observed from the moment the investigation against the suspect begins until the criminal proceedings, including the appeal, are concluded. Rights at trial include the right to equality before the law; the right to be tried by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal established by law; the right to a fair hearing; the right to a public hearing; the presumption of innocence; the right not to be compelled to confess or testify; the exclusion of evidence elicited as a result of torture or other compulsion; the right to be tried without undue delay; the right to defend oneself in person or through counsel; the right to be present at trial and appeal; the right to call and examine witnesses; and the right to an interpreter and translation.

The challenges of dealing effectively with the threat of terror call for a need to re-assess the concept of the right to a fair trial. What evidence may be admitted in terror proceedings? Are there exceptions that might justify waiving the right to a public trial? Can the defendant be excluded from proceedings on grounds of national security or witness security concerns? These and many related issues need to be re-examined in the context of responding to threats of terror.

1. Right of an accused to be present

If the accused is not present at trial, such a trial may be referred to as a trial in absentia. There is no absolute prohibition on trials in absentia under international law. However, trials in absentia would compromise the ability of an accused person to exercise certain rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, including the right to adequately prepare a defence, to communicate with counsel of choice and to examine witnesses. As one legal commentator has noted, "One of the most important elements of due process in the realm of criminal procedure and procedural equality between the parties is the physical presence of the accused at trial." Both the ICTY and ICTR statutes explicitly prohibit trials in absentia and declare, in identical terms, that the "accused shall be entitled... in full equality... to be tried in his presence, and to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing[.]" Trials in absentia are likewise prohibited by the ICC statute, although the United Nations Human Rights Commission has opined that trials in absentia are permissible in certain circumstances if the state makes "sufficient efforts with a view to informing the [accused] about the impending court proceedings, thus enabling him to prepare his defense."

Subject to the possible exceptions relating to protection of national security, the right of an accused person to be present during his or her trial is a fundamental part of internationally recognized fair trial norms. The statutes of the both the ICTR and ICTY contain provisions, to be discussed at a later point, which address the issue of national security interests which might, if adopted in some modified form by the commissions, mitigate the need for excluding an accused, or at least his civilian counsel, from closed proceedings. However, we now turn to an examination of evidential rules which may or may not compromise the right of the defendant to know and understand the evidence presented against him.

2. Hearsay evidence

Common law legal systems have historically restricted or excluded hearsay evidence. Civil law systems have on the other hand been flexible in admitting hearsay evidence. The ad hoc United Nations criminal tribunals have similarly adopted a very open approach to what can be presented as evidence in court.

While neither the ICTY nor the ICTR statutes address the concept of hearsay evidence directly, it is well settled in ICTY case law that hearsay evidence is acceptable. A line of cases beginning with the Prosecutor v. Tadic have interpreted Rules 89(c) and 89(d) of the ICTY's Rules of Procedure and Evidence as indicative of how to evaluate hearsay evidence, noting that "any relevant evidence" may be admitted provided it has "probative value" and that such value not be "substantially outweighed by the need to ensure a fair trial." The ICTY Appeals Chamber consequently identified three guiding criteria for the admission of hearsay evidence, namely, that its reliability must be based on its voluntarism, its truthfulness, and its trustworthiness. Moreover, the Tribunal has emphasized that ICTY judges are fit to assess the probative value and reliability of such evidence, and to decide how much weight to accord it.

In an attempt to further clarify the Tribunal's hearsay jurisprudence, the ICTY later adopted Rule 92bis, which clearly states that written (though not oral) statements shall be admissible if they include a "declaration by the person making the written statement that the contents... are true and correct to the best of that person's knowledge and belief." It also allows the admission of affidavits on matters that are cumulative in nature, consist of statistical analysis, concern the impact of a crime on its victims, and relate to the background of a conflict, the character of the accused, and sentencing issues. As the ICTY and ICTR's Rules are institutionally linked, this amendment similarly applies to the ICTR as well. Even before the adoption of Rule 92bis, however, the ICTR had also upheld the admissibility of hearsay evidence. Like the ICTY, it held that while in principle hearsay evidence should not necessarily be excluded, it should nevertheless be handled cautiously and with due regard to the tests of relevance, probative value, and reliability.

The Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the International Criminal Court, like those of the United Nations, are silent on the exclusion of hearsay or otherwise indirectly obtained evidence, although Article 69(4) adopts an admissibility test similar to that of the ICTY and ICTR, i.e., the ICC may rule on the relevance or admissibility of any evidence as long as takes into account its probative value and any prejudice that it may cause to a fair trial or fair assessment of the testimony.

In light of this, the pre-Hamdan military commission's rules standards for hearsay evidence are not inconsistent with the standards of international criminal law. In any event, the issue as to whether or not hearsay evidence should be admitted in trials of terrorist suspects can not be determined in isolation from the context of the threat of terrorism. Whereas international criminal tribunals have dealt and are still dealing with vanquished war criminals, trials of terrorist suspects will involve defendants supported by active and powerful networks capable of endangering witnesses or threatening entire communities. There would few eye witnesses or insiders of terror networks willing to testify, first because conspiracy cells are compartmentalized and second, because witnesses fear revenge.

3. Admissibility of Evidence obtained from foreign state entities.

Most terror suspects will be apprehended by agencies of foreign states. Therefore, the first contact of most terror suspects with law enforcement or public security agencies before their extradition or rendition to the US will be these foreign entities. The agencies in question will often have carried out interrogations of suspects before delivering the suspects along with the evidence. At least some of the evidence will have been gathered by military or intelligence rather than by police or prosecutorial agencies. Part of the evidence will often not have been voluntary. It will be necessary for judicial authorities to be on guard to ensure that the evidence, especially confessions or admissions of guilt, which will come into the possession of prosecutors and investigators will not be tainted by torture or coercion.

However, the determination of whether or not confessions or other information has been obtained by torture may be difficult to make without delving into a shadowy, often classified set of military and security operations, either by the United States or by another State. When examining evidence, submitting it for the record at trial, and seeking to defend against such evidence, the national security concerns of the states carrying out these activities may come into conflict of the accused's right to defend himself. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the rules which have been developed on the handling of information which is classified or which the public revelation of might compromise the national security of a state.

B. National Security Concerns

The rules of both the ICTR and the ICTY recognize the legitimacy of national security concerns of states assisting the two tribunals. It was understood and was provided for in the tribunals' rules of procedure and evidence that the sensitive nature of some of the assistance provided by states to the tribunals might preclude the conduct of public proceedings and or require restrictions on the submission of certain types of evidence. Rule 54(F) of the ICTY and ICTR's Rules of Evidence and Procedure ("RPE") were specifically constructed to address national security concerns of this nature. According to the rule, a state having concerns over the national security impact of a public hearing shall "file a notice of its objection not less than five days before the date of the hearing" and may request in camera or ex parte proceedings, or the use of documents submitted in redacted form accompanied by an affidavit signed by a senior official explaining the reasons for the document's restrictions.

Additionally, the subpoena of witnesses whose appearance or testimony at court could endanger national security was addressed by the ICTY in the Blaskic case, in which a French military officer's appearance at the Tribunal was judged by France to raise national security concerns. The Chamber concluded that, subject to certain conditions, the officer was able to testify without compromising "the necessary bounds of confidentiality." These conditions included a limitation of the scope of questions asked by the Prosecutor and the Defense, the witnesses' ability to state that requested information is wholly or in part confidential, the authorization of representatives of the French government to be present in the courtroom and to address the Trial Chambers, if necessary outside the presence of the Witness and/or parties, and "to present any reasoned request which they believe necessary for the protection of the higher interests they have been assigned to protect[.]"

Not every piece of information is subject to disclosure or exclusion based on national security. According to Rule 70(B) of both Tribunals on the production of evidence,

If the Prosecutor is in possession of information which has been provided to him on a confidential basis and which has been used solely for the purpose of generating new evidence, that initial information and its origin shall not be disclosed by the Prosecutor without the consent of the person or entity providing the initial information and shall in any event not be given in evidence without prior disclosure to the accused.

Rule 70(D) continues:

If the Prosecutor calls as a witness the person providing, or a representative of the entity providing, information under this Rule, the Trial Chamber may not compel the witness to answer any question the witness declines to answer on grounds of confidentiality.

Thus, taking Rule 54(F), Rule 70 and the Blaskic precedent together, a government having national security concerns about the use of evidence or the testimony of witnesses may file an objection in advance of a hearing, explain their objections outside the presence of the witness and/or parties, and request that information either not be presented or be presented in redacted form. The Prosecution is not required to present the source of confidential information that is used solely to generate new evidence, and witnesses may not be compelled to respond to questions whose answers are confidential.

In order to determine whether the rules on non-disclosure and confidentiality are to be applied, the Prosecutor may make use of Rule 66(C) of the tribunals' statutes:

Where information or materials are in the possession of the Prosecutor, the disclosure of which may prejudice further or ongoing investigations, or for any other reasons may be contrary to the public interest or affect the security interests of any State, the Prosecutor may apply to the Trial Chamber sitting in camera to be relieved from the obligation to disclose pursuant to Sub-rule (A) and (B). When making such an application the Prosecutor shall provide the Trial Chamber, and only the Trial Chamber, with the information or materials that are sought to be kept confidential.

Thus, although confidential information may be kept from the parties, a presentation of the classified material as well as arguments why it should not be disclosed must be made to the trial judges. It is the judges who are responsible for determining if a Prosecutor's request for non-disclosure is valid, but that determination may be made on the basis of national security concerns, the public interest, or any further or ongoing investigations. Additionally, parties to proceedings at the ICTY and ICTR may request transcripts of closed proceedings in other trials, which, upon permission by the Trial Chamber, may be redacted to preserve their confidential nature. It is assumed that grounds for confidentiality protections have already been met through the use of closed chambers for the original testimony.

If rules of procedure of international criminal courts permit states which have assisted them to seek orders for the non-disclosure of information which might jeopardize their national interest, the availability of such remedies (the use of summaries and redactions of classified information, in camera proceedings and ex parte proceedings, etc.) in proceedings in U.S. courts trying suspected terror suspects would not by analogy violate international standards of fair trial.

C. Witness Protection

International tribunals must respect the national security concerns of cooperating states, but they must also take note of the safety and security of those individuals who cooperate with and testify before them. The dangers which persons accused of very grave offences and their networks pose to witnesses should never be underestimated. In my experience with the Rwanda Tribunal, it has often been the case that the network of persons supporting defendants have used information obtained through the disclosure process to threaten witnesses even before the trial. Serious threats to the security of witnesses call for considerations of questions such as the following: Can the identity of the witnesses be kept anonymous? Could their physical presence be dispensed with? Can the court impose restrictions on disclosure of some of the evidence to the accused? Could a witness dispense with a personal appearance and participate in the proceedings by swearing depositions or affidavits?

Both the ICTY and ICTR have had to grapple with the problem of protection of witnesses. The two tribunals have in practice been willing to place restrictions on the right to disclosure. To limit the disclosure of information about protected witnesses to only what is necessary for the trial, a number of regulations exist on the disclosure of witness identity. Rule 69 regarding the protection of victims and witnesses allows the Trial Chamber, upon request by the Prosecutor, to order non-disclosure of the identity of a witness who may be in danger or at risk, although their identity must be disclosed to both the prosecution and the defense "in sufficient time prior to the trial to allow adequate time for preparation of the prosecution and the defence." That time period has at the ICTR been around 21 days. At the ICTR, at least one case has been determined to be not less than 30 days before the trial date. Additionally, the types of information which constitute a witness' "identity", such as name or age, do not include the witness' current address, making safety concerns a continuing priority.

Civil law systems have a long history of using depositions and affidavit evidence in criminal proceedings. Whereas criminal courts in the United States, for example, grant both the defendant and the prosecution the right to compel witnesses to appear at trial, "[i]n most instances, the evidence of witnesses [in civil law systems] will be accepted in written form, with no need for live testimony."

The Rules of Procedure and Evidence for the ICTY and ICTR permit the taking of depositions by witnesses who do not physically appear before the tribunals. Trial chambers may order the taking of such depositions at their own initiative or at the request of either party, when "the interests of justice" so dictate. Cross-examination by the opposing party is permitted, however, during the taking of the deposition. Depositions may be taken either at or away from the seat of the tribunals, and may also be given by means of video-conference technology.

The use of depositions and affidavits at trial is both consistent with international fair trial standards and may be an effective substitute for the actual appearance of witnesses. This is of particular concern for military commanders and interrogators whose testimony may be required but whose duties require their presence in the field. Likewise, local witnesses may have legitimate fears of testifying in person and be disinclined to appear in person.

Witnesses may even qualify for anonymity. In order to qualify for such protection, witnesses must satisfy five conditions: There must be real fear for the safety of the witness or her or his family; the testimony of the particular witness must be important to the prosecutor's case; the Trial Chamber must be satisfied that there is no prima facie evidence that the witness is untrustworthy; the ineffectiveness or non-existence of a witness protection programme is another point that has considerable bearing on any decision to grant anonymity; measures taken should be strictly necessary. If a less restrictive measure can secure the required protection, that measure should be applied.

The protection of witness identity is for the safety of the witness himself, rather than for wider security or public order concerns, and the accused still has the right to know and confront his accuser during trial proceedings, albeit through use of video-conferencing or other distortive techniques.

The witness protection mechanisms of the international criminal tribunals have by and large been effective in ensuring the security of witnesses. The nature of threats to witnesses in war crimes prosecutions differs, however, from the threats posed to witnesses in cases of terror violence. International criminal tribunals conduct trials of vanquished war criminals whereas trials of persons suspected of terror violence involve organized networks able and eager to use violent means to pursue their goals. My opinion is that the approach which international criminal tribunals have taken in dealing with witness protection issues during war crimes trials would not be entirely appropriate to dealing with the dangers facing witnesses in terrorism trials in general.

Conclusion

The right to a fair trial is a fundamental human right. It has been effectively safeguarded by international tribunals during their war crimes proceedings. However, war crimes prosecutions differ from trials of suspected perpetrators of terrorist violence in the sense that the war of terror remains ongoing and its architects retain the capacity both to take revenge against witnesses and to threaten the security of states. The obvious and potentially catastrophic risks which terrorism poses both to national security in general and to witnesses in cases of terrorism in particular call for consideration of new approaches to the question of how to ensure fair trial.

The experiences of international criminal tribunals and jurisprudence from civil law systems which have conducted war crimes trials have lessons to offer as to how the conflicting requirements to ensure compliance with international human rights norms relating to the right to fair trials while protecting witnesses and ensuring national security could be harmonized.

Given the state of affairs, my recommendations are:

- The exclusion of defendants from proceedings violates the right to a fair trial and is highly undesirable;

- Hearsay evidence of probative value should continue to be admissible, subject to appropriate safeguards to ensure that it has not been obtained through torture or coercion;

- The possibility of utilizing depositions and affidavit evidence should be explored;

- Consideration should be given to making greater use of appropriate mechanisms for protection of witnesses such as in camera proceedings and anonymous witnesses;

- The scope of current rules relating to disclosure could be reviewed to minimize the risks posed to the witnesses or national security while providing defendants with enough information to answer the charges against them;

- Procedural rules ought to be developed to discourage or minimize defendants' attempts to politicize proceedings or to abuse the criminal justice process in general.

Again Mr. Chairman, thank you for calling this hearing today and for giving me the opportunity to speak on this important issue.

The views expressed in this testimony are those of the author, not the U.S. Institute of Peace, which does not take positions on policy issues.