How the ICC’s Warrant for Putin Could Impact the Ukraine War

While this is a significant step, it will be critical for the international community to continue to pursue accountability for the crime of aggression.

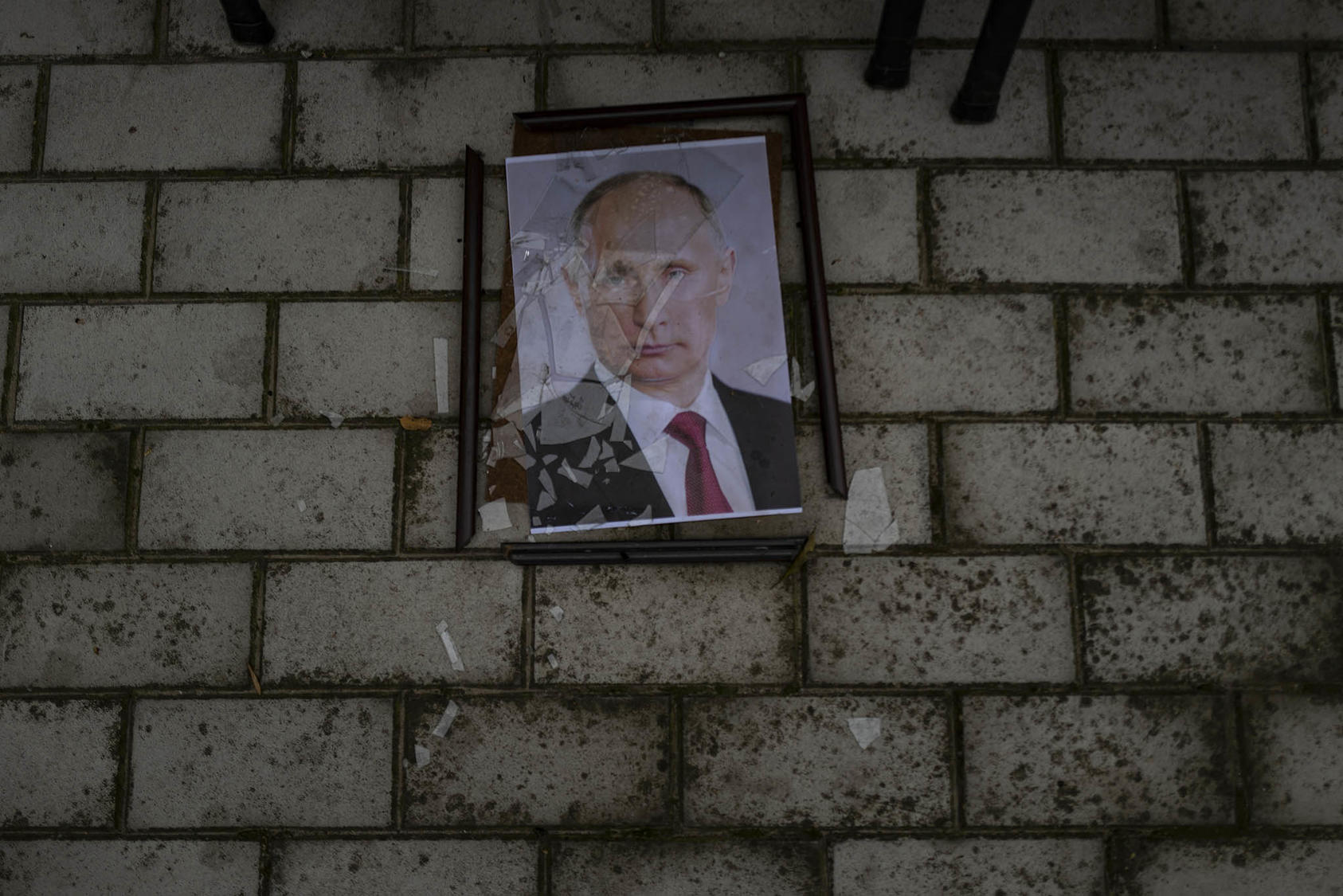

The International Criminal Court (ICC) announced last Friday that it had issued arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Presidential Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova. According to a statement issued by the ICC, Putin and Lvova-Belova are alleged to have committed the war crimes of “unlawful deportation of population (children) and that of unlawful transfer of population (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation” beginning in at least February 24, 2022. USIP’s Lauren Baillie, Heather Ashby and Mary Glantz discuss the impacts of these warrants on Putin and on the war in Ukraine.

What do the warrants mean for international criminal accountability for Russian crimes in Ukraine?

Baillie: The issuance of the warrants indicates that the ICC intends to make good on its promise to hold Russian leadership accountable for atrocity crimes committed in Ukraine. The decision to pursue charges against Putin sends a strong signal to lower-level perpetrators that no one is immune from prosecution and may serve as a deterrent to Russian officials engaged in criminal activity. Further, while Putin is not the first sitting head of state to be indicted by the ICC, he is the first leader of a country that is a permanent member, or P5, of the U.N. Security Council to be indicted. With two P5 countries arguably committing atrocity crimes (China being the other), the impact of this decision could resonate beyond Russia.

The warrants address conduct that constitutes one of Russia’s most egregious alleged crimes committed in Ukraine: the forcible transfer of children from occupied territories of Ukraine to Russia. According to reports from the State Department’s Conflict Observatory, at least 6,000 children have been forcibly transferred from Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, with many placed in orphanages or adoptive Russian families and most subjected to some form of “re-education.” Although the warrants recognize these crimes as war crimes, commentators have made a strong case that the conduct in question constitutes genocide and crimes against humanity. The prosecutor’s decision to pursue these crimes as war crimes may be an indication of his assessment of the strength of the evidence collected to date, particularly related to intent. With both the alleged crimes and evidence collection ongoing, however, charges may be amended as the investigation proceeds.

While the issuance of the warrants is a significant step forward for international accountability for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it will be critical for the international community to continue to pursue accountability for the crime of aggression. The establishment of a special tribunal for the crime of aggression has been the subject of considerable international debate, but consensus has yet to emerge around whether to establish the court and the appropriate modality for doing so. It is possible that members of the international community may see the ICC arrest warrants as sufficient for holding Putin accountable. The crime of aggression falls squarely outside of the ICC’s investigation, however, and this gap will exist regardless of the court’s indictment. Thus, even as they celebrate the ICC’s announcement, the Ukrainian government and like-minded partners should continue to press for international support for the establishment of the tribunal to ensure that Russian leaders are held accountable for the full breadth of crimes committed.

What impact will the arrest warrants for Putin and Lvova-Belova have on Russian foreign policy?

Ashby: The ICC arrest warrants are already having an impact on Putin internationally, which will only increase over the course of the year as pressure mounts on countries to distance themselves from Putin and Russia. Soon after the ICC’s announcement, South Africa — which is a signatory to the ICC — was urged by the international community to uphold its obligation to the statute and arrest Putin if he travels to the country for the BRICS summit in August 2023. Besides hindering potential international travel for Putin, the warrants make it less appealing for heads of state and other senior foreign officials to travel to Russia for meetings that will feature Putin.

This summer the Russian government is hosting its second Russia-Africa Summit, the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum and the Eastern Economic Forum, which in the past have showcased Russia’s partnerships with a variety of countries. Those events also feed into Putin’s narratives about Russia’s prominence on the global stage. The lack of strong foreign attendance at senior levels for those events in Russia would be detrimental to Russian foreign policy amid a pivot from focusing on Europe and the United States to the Global South, where it is building partnerships with countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Beyond Putin, the arrest warrants could make it less appealing for countries in the Global South to host Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and other senior Russian government officials. There is an open question on whether additional Russian government officials will soon face ICC arrest warrants for their role in Russia’s war against Ukraine. With 123 countries as signatories to the Rome statute, the places where Russian officials can travel and actively engage with foreign governments will become smaller. Furthermore, the ICC investigation into Russian war crimes could also ensnare Wagner Group founder Yevgeny Prigozhin and Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic, who have both actively boasted about their roles in the war.

Unfortunately, the ICC warrant for Lvova-Belova will not have significant international impact for Russian foreign policy. Lvova-Belova has not traveled much internationally since the full-scale invasion with her trips focused primarily on Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine. However, the ICC warrant for Lvova-Belova further undermines Russian justifications since 2014 for its invasion of Ukraine, which Russian government officials argued were attempts to protect Russian-speaking Ukrainians from genocide.

Overall, the stakes are becoming increasingly high for foreign governments that wish to engage with Putin and Russian government officials. Combined with sanctions, the ICC warrants make it harder for countries to turn a blind eye to Russian actions in Ukraine and the brutality of its war.

What impact do the arrest warrants have on Putin domestically?

Glantz: It is doubtful that these warrants will have any impact on Putin in the domestic political sphere. There is little indication that public opinion will be affected by the news. Russian press coverage — which has been sparse and emphasizes that Russia does not recognize the ICC and considers its charges false — is helping to ensure this. The government’s official newspaper, Rossisskaya Gazeta, describes the arrest warrant as “a rotten political show and corrupt, opportunistic justice in the interests of the countries of the ‘golden billion,’” a reference to anti-Western Russian conspiracy. In addition, the Russian press has highlighted that the United States also does not recognize the ICC.

A more significant possible impact would be among the elites helping maintain Putin’s power. In this regard, there are some whispers on social media that the ICC warrant may complicate Putin’s position by both increasing elites’ unhappiness with him (the war crimes accusation could complicate their ability to travel freely abroad) and, as a result, by heightening his suspicion of the people around him.

How do these warrants support Ukrainian-led accountability efforts?

Baillie: The issuance of the warrants fills a gap in Ukrainian prosecution efforts and provides them additional legitimacy. Ukraine has led the charge in holding Russian actors accountable for atrocity crimes committed on its territory and will prosecute the vast majority of alleged offenders. However, Ukrainian courts cannot prosecute Russian leadership due to the principle of head-of-state immunity, which precludes states from indicting sitting heads of state of other countries. The Ukrainian government has looked to the ICC to fill this gap, despite the fact that Ukraine is not a party to the Rome Statute. Not only had Ukraine agreed to ICC jurisdiction over crimes committed since Russia’s 2014 invasion, 43 states party to the Rome Statute referred the situation to the prosecutor for review, allowing the prosecutor to quickly open an investigation to respond to the 2022 full-scale invasion. With the issuance of the warrants, the ICC has taken the initiative to fill the gap created by head-of-state immunity. This is a morale boost for Ukrainian prosecutors and the Ukrainian people more broadly, as they seek justice for crimes committed against them.

The ICC arrest warrants also provide further legitimacy to Ukraine’s ongoing investigations and prosecutions by internationally recognizing the crimes they are investigating. Ukraine’s domestic justice system is under tremendous pressure to prosecute a substantial number of war crimes cases. As of this writing, more than 74,500 war crimes have been reported and only 26 trials have been conducted. The prosecution of war crimes is therefore likely to be a long-term process, one that will require sustained will and resources. International recognition of the crimes they are investigating may provide motivation to Ukrainian prosecutors as they face down their formidable caseloads.