The 1963 Franco-German Reconciliation Treaty: A Guide for Japan and South Korea?

Seoul and Tokyo can draw on lessons from European history as they seek to ‘rethink’ their relationship.

Relations between Japan and South Korea are at a dead end. Officials on both sides have acknowledged the need to improve relations. Beset by stark differences over compensation for historical issues of coerced sexual slaves (so-called comfort women) and forced labor, and contemporary issues of trade, the relationship needs a game changer to alter course. South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol has called for a “rethink” of the relationship. Conflict-resolution practices beyond East Asia could help us to think outside the box.

Could a variant of the successful 1963 Franco-German reconciliation treaty help resolve the impasse in Japan-South Korea relations? While the Franco-German relationship has faced vicissitudes, for almost 60 years, the treaty has remained an anchor and framework for confronting and managing differences, and for cooperating on all manner of bilateral, regional and international issues. The following analysis focuses on five dimensions of the 1963 treaty that may have lessons for the South Korea-Japan relationship: 1) setting and origins; 2) dialogue and preparation; 3) personalities and leadership; 4) provisions and institutions; and 5) the role of the United States.

Setting and Origins

In the 18 months before the Franco-German Elysée Treaty’s conclusion on January 22, 1963, the international system was in a fragile state of flux. In August 1961, East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic, erected the Berlin Wall. The next year, the world came to the nuclear precipice with the U.S.-Soviet missile crisis in Cuba. One week before the treaty’s signing, French President Charles de Gaulle vetoed the United Kingdom’s bid to join the European Economic Community (EEC).

During this early stage of European integration, France and West Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, held differing perspectives: a French intergovernmental community versus a German supranational community. While they maintained differences over the EEC and NATO, both France and West Germany saw the treaty as a way to create dependability and predictability in Europe and present an independent voice in global affairs. The treaty was a mechanism for embedding Germany in Western Europe and an opportunity for demonstrating Germany’s commitment to peace.

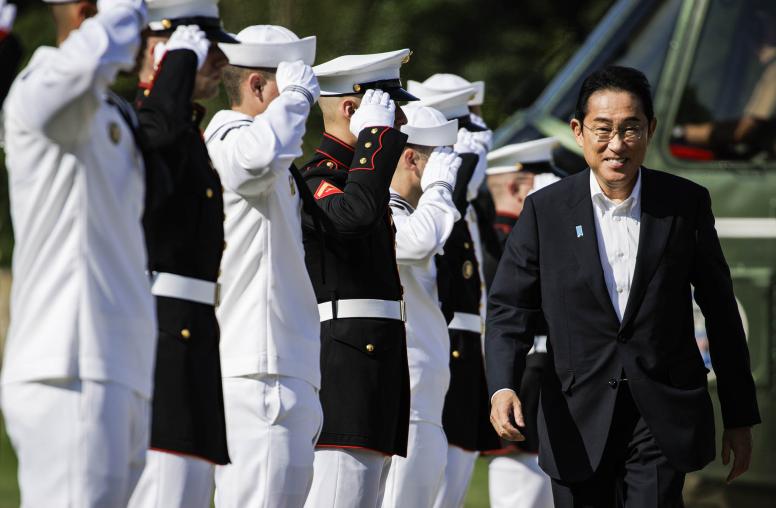

The international system today is undergoing an even more dramatic shift. Both Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Yoon have recognized three major global and regional challenges: the Russian invasion of Ukraine; a rising China in economic, strategic and military terms; and an increasingly bellicose North Korea. The South Korean and Japanese foreign ministers have agreed that “bilateral and trilateral strategic collaboration also involving the United States is needed more than ever in the current international situation.” Unusual times call for unusual action. Thinking about the Elysée Treaty reveals new possibilities.

Dialogue and Preparation

The Franco-German treaty’s gestation occurred over a five-year period, starting with German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s first meeting with de Gaulle in France as chancellor. They met in de Gaulle’s home in September 1958, lending a symbol of personal friendship beyond their political ties. An intense epistolary exchange (some 40 letters) and visits in both directions (15 times) followed, as well as exchanges in the EEC framework. Officials in various cabinet ministries and politicians from the two countries also frequently discussed policy issues in bilateral and regional fora.

In the Japanese-South Korean case, a reconciliation treaty is not imminent, but the dialogue track seems to have commenced through phone calls, letters and visits at the highest level. Kishida called the president-elect after Yoon’s March win. The two men agreed to start a new chapter in their relationship, with Yoon emphasizing the need for resolution of bilateral differences in a “reasonable, mutually beneficial manner.” They also met, albeit with hesitation, together with U.S. President Joe Biden on the sidelines of the NATO summit in June 2022.

Six weeks after the March call, Kishida and Japanese cabinet ministers met with a South Korean delegation representing Yoon to discuss historical and contemporary differences. In a letter to Kishida, Yoon is reported to have floated the idea of resuscitating the 1998 Obuchi-Kim declaration, which promised the possibility of future-oriented reconciliation based on recognition of history.

Kishida sent his foreign minister, Yoshimasa Hayashi, to Yoon’s inaugural, obviating the opposition of conservatives in the Liberal Democratic Party to Kishida himself attending the ceremony. In a personal letter to Yoon, Kishida underscored the urgency of strategic cooperation. The foreign minister and president committed to continuing dialogue and betterment of ties.

Hayashi and his South Korean counterpart, Park Jin, met at Yoon’s inauguration where they opened the possibility of a second meeting in Tokyo to discuss substantive issues and the question of a face-to-face meeting between Kishida and Yoon. At the second meeting in Tokyo in July, the two foreign ministers agreed to find a quick solution to the forced labor issue. Given determined and vociferous political naysayers and seesawing popularity ratings in both countries, the two sides are engaged in a delicate minuet. Their next moves in this elaborate dance will require clear-eyed, pragmatic leadership. A helpful step is Yoon’s creation in June of a public-private advisory council on the forced labor issue.

Personalities and Leadership

In their intense five-year dialogue, de Gaulle and Adenauer developed deep friendship and trust based on personal chemistry and spiritual Catholicism. They were seasoned politicians with crystalline goals to direct them and political backbones to withstand the daunting domestic opposition to their plans. Both demonstrated moral leadership and profound courage. They had both been tested already many times in their long careers, especially in World War II, in which they both stood up to fascism. When they began down the path of reconciliation, they evinced wisdom and stature.

On the other hand, Kishida and Yoon barely know each other. Kishida has a depth of policy experience, but Yoon is a political neophyte. However, they both bring personal advantages to the burgeoning relationship. They are both political conservatives, reducing the danger of ideological clashes. Yoon was a top prosecutor, which could mean a deftness in dealing with the legal intricacies of the historical issues. As Japan’s longest-serving foreign minister, Kishida was an experienced negotiator, including on the controversial and ill-fated 2015 sexual slavery compensation agreement, so he knows where the pitfalls are on this contentious issue. They both need to show courage and political leadership to bring along domestic opinion on a difficult, but not impossible, road ahead.

Provisions and Institutions

De Gaulle held Adenauer in high esteem yet recognized that partnership had to be enshrined in something less subject to change and chance than personal chemistry. He wanted to embed Germany for the long-term through permanent institutions. The treaty recognized the past of hereditary enmity and noted that it would “[bring] an end to the age-old rivalries.”

In a novel approach, the treaty focused on institutions at both the societal and governmental levels. Starting already in the immediate postwar period, years before the 1963 treaty, civil society — religious, educational, economic, cultural and political actors — was an essential ingredient of a new relationship. The treaty formalized that interaction, particularly in the creation of the Franco-German Youth Office for the promotion of exchanges “between … pupils, students, young artists and workers.”

On the governmental side, the treaty broached the two broad areas of politics and defense. On the former, the treaty provided for a minimum of two meetings every year between heads of state and government and four times every year between foreign ministers. On defense, the ministers were to meet four times a year, and the chiefs of staff were to come together at least once every two months. The treaty also encouraged exchanges between armed forces personnel. These regular meetings instilled habits of cooperation and mutual learning. The significance of institutions was borne out immediately: from 1963 to 1966, when political relations were very difficult between de Gaulle and Ludwig Erhard, Adenauer’s successor, the two leaders’ annual meetings prescribed in the treaty took place, as did the foreign ministers’ meetings. In later years, the neighbors created Franco-German Councils in defense, economics, finance, culture and the environment.

A comparable Japan-South Korea reconciliation treaty would take time, but an interim step could be the revival of the 1998 Obuchi-Kim joint declaration. The declaration came about because of deep tension over historical issues, but it failed to deal with them specifically. Whereas it talked about past and future, history dominated relations thereafter. The declaration also lacked an enforcement mechanism. All of these lessons of failed implementation should be kept in mind if the declaration finds new life. Some analysts have referred to the 1965 normalization treaty and its third-party arbitration mechanism for the resolution of compensation claims, but the joint declaration may be a better framework for resolution as its language has not been open to divisive interpretation.

Like the Franco-German treaty, the joint declaration provided for cooperation between societies and between governments. The joint declaration referred to expansion of “cultural and personnel exchanges” and promotion of interactions “among various groups and regions at various levels … inter alia researchers, teachers, journalists, civic circles and other diverse groups.” It also emphasized the crucial involvement of young people.

People-to-people exchanges between Japan and South Korea have occurred since 1965, but they were unpredictable, inconsistent and intermittent. The COVID-19 pandemic has further dented societal interaction. Analysts advocate the ramping up of societal activity, including Sheila Smith’s proposal to use as a model the 1961 Japan-US Cultural and Educational Interchange Commission, which entailed “a network of exchanges in the arts, education, civil society, and local community leaders.”

Regarding official exchanges, the 1998 joint declaration underscored the strengthening of “mutual visits and the close consultations between them, to conduct these visits and consultations regularly and to further enhance Minister-level consultations in various areas.” Currently, elements of an official dialogue track are evident in Japanese-South Korean relations, but they could be expanded and routinized and eventually formalized in something akin to the unimplemented 1998 joint declaration.

The dialogue track could prioritize negotiations over wartime forced labor and sexual slavery. Already in 2014, Martina Timmermann suggested as a model the German fund (Foundation for Remembrance, Responsibility and Future), which emanated in 2000 from the slave and forced labor negotiations between Germany and its victims. It was funded equally by the German government, making it official, and private companies. The fund made compensation payments to victims. An overlooked part of the foundation is its work for the future, in which it funds educational projects regarding history and its contemporary consequences. A Japanese fund could encompass a similar educational track that would not forget history but manage it productively. This educational track comports with the proposal by Seiko Mimaki to permit nongovernmental actors to establish the framework for negotiating sexual slavery compensation.

Trade disputes are amenable to official bilateral resolution, but private business involvement could lubricate the process. Furthermore, the negotiations could be located in a trilateral cooperation mechanism among Japan, South Korea and the United States, such as the newly launched Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity. In general, U.S. mediation between Japan and South Korea on thorny problems could be productive.

The Role of the United States

The influence of a third party (i.e., those who favored NATO) temporarily impeded the political passage of the Franco-German treaty. In West Germany, opinion was split between Atlanticists, who feared a treaty would have a negative impact on transatlantic relations, and Gaullists, who supported the agreement. The treaty made only glancing mention of NATO and no mention of the United States, as noted with great concern by then U.S. President John F. Kennedy and U.S. officials. The Atlanticists’ and U.S. concerns were resolved during ratification in the Bundestag when deputies insisted on a preamble emphasizing the importance of both NATO and the United States.

Similar to the eventual outcome of the Franco-German treaty text, U.S. involvement in negotiations and cooperation between Japan and South Korea is not an obstacle, but rather a plus in economic and strategic terms. Such involvement could mean that trade restrictions (e.g., Japanese export controls on the materials used for semiconductors) and sexual slavery issues are approached as universal challenges, thereby blunting national perspectives. Trilateral and international arrangements neither dilute nor replace bilateral interaction, but rather augment it.

Sixty years ago, in a daring treaty, two courageous leaders put behind them the past of ingrained Franco-German conflict. South Korean and Japanese leaders could launch a similarly audacious move in the medium term as the culmination of a two-step process entailing regular dialogue and the 1998 joint declaration’s revival. Such a process could bring stability and reliability to a brittle relationship in an increasingly dangerous world.

Lily Gardner Feldman is a senior fellow at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University.