The Afghan Refugee Crisis in 2016

Hundreds of thousands of documented and undocumented refugees returned to Afghanistan in 2016, joining more than one million internally displaced within the country. International agencies warn of a humanitarian crisis that would affect hundreds of thousands of people as returnees struggle to meet basic needs. This Peace Brief provides an overview of the situation at the end of 2016, focusing on those returning from Pakistan, the humanitarian situation, and the security implications of the influx.

Summary

- In early 2016, an estimated one million registered and 1.5 million unregistered Afghan refugees lived in Pakistan. Similar numbers lived in Iran.

- Hundreds of thousands of documented and undocumented refugees returned to Afghanistan in 2016, joining more than one million internally displaced persons.

- Large-scale returns of Afghan refugees from Pakistan, described by authorities and aid agencies as spontaneous, are driven by political tension between the two countries.

- The needs of returnees, such as basic services or assistance with integration into Afghanistan, are not being fully met.

- International agencies warn of a humanitarian crisis as returnees struggle to meet basic needs such as shelter and food.

Background

Pakistan has for several years imposed shifting deadlines for the return of Afghan refugees within Pakistan who fled their own country in response to ongoing conflicts there. The most recent such deadline was March 2017. Refugee anxieties about their future continue to mount as thousands remain in detention centers in difficult and often harsh conditions.1 Pakistani authorities have imposed strict restrictions on refugee movement within the country, contributing to their return to Afghanistan.

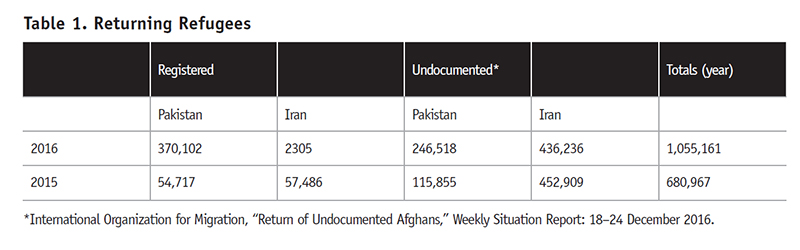

At the beginning of 2016, an estimated one million registered and 1.5 million undocumented Afghan refugees were believed to be living in Pakistan, and another one million and 1.5 million respectively in Iran.2 By the end of the year, returnees from Pakistan numbered 616,620, of whom 246,518 were undocumented and 370,102 documented.3 The numbers for returnees from Iran were 436,236 undocumented and 2,305 documented.4 Many of the returns are referred to as spontaneous—indicating voluntary return—but in reality are often coerced or in coercive circumstances in which they feel that they have little choice but to leave and are given little opportunity to plan.

More than one million people within Afghanistan have been internally displaced because of violence and ongoing war in their communities. The UN High Commissioner of Refugees notes that this figure is likely an underestimate given challenges in data collection. One such challenge is that a significant percentage of returnees are likely to become secondarily displaced because of the spontaneous (unplanned) nature of their return and the challenges on arrival. Many internally displaced persons (IDPs) live in temporary shelters, often in urban areas.5 Young people make up half of Afghanistan’s population but a disproportionate percentage of IDPs—between 57 percent and 61 percent. IDPs continue to have significant needs and tend to become more vulnerable the longer their displacement lasts, especially women and girls in urban areas.6

Humanitarian Crisis and Security Concerns

Returns have been concentrated in a handful of provincial centers, and an overwhelming majority find themselves in areas of continued fighting.7 A related humanitarian crisis would affect hundreds of thousands of people.

The UN request for humanitarian assistance for returnees has so far received only half the contributions needed to address vulnerable populations—$82.4 million of $152 million.8 In September 2016, the International Organization on Migrations warned that “the situation is dire and we expect it to become far worse as winter approaches.”9 Returnees are entering a country wracked by violence, economic instability, and lack of basic services in most parts of the country. Insecurity remains a serious concern. Just over eleven thousand civilian casualties (3,545 deaths and 7,457 injured) were documented in 2015, exceeding by 4 percent the record set the year before.10

Disputes over housing, land, and property between returnees and current occupants have also been reported. Such intra-family and intra-community tensions have the potential to escalate to a larger conflict that could threaten the stability of communities, particularly when the Taliban offer help in addressing grievances. Social divisions can be exacerbated when so many are in need but only returnees are seen to receive support. According to a local organization, little is being done to address tensions between communities—many of whom have themselves at one point been returnees—and current returnees.

Despite the scarcity of empirical research on related security implications, the inflow from Pakistan, Iran, and Europe has caused concern among nongovernmental organizations working with returnees and government institutions handling security in Afghanistan. Security analysts are aware, interviews reveal, that terrorists can disguise themselves as returnees to enter and move around the country undetected. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that returnees may be at greater risk of radicalization and recruitment into criminal and violent extremist groups.

Economic and Social Tensions

The large influx of returnees adds strain to an already weak economy. Currently, 39 percent of the population live below the poverty line and more than eleven million are severely and moderately food insecure.11 At 40 percent, unemployment has reached an all-time high, jumping a staggering 400 percent between 2013 and 2015.12 Afghanistan’s youth population is among the world’s youngest and fastest growing, and close to 40 percent of returnees are males younger than eighteen, putting additional strain on the labor market. Insecurity and lack of school facilities and trained teachers mean that a significant number of school-age children are deprived of education, and returnee children are more likely to remain out of school than their peers.13 The lack of livelihood and education opportunities can make unemployed youth more at risk of turning to illicit activities to support themselves and their families.14

A myriad of social problems have also resulted from the forced nature of the returns. Some families are compelled to leave homes they have lived in for decades with little notice and often without time to gather their belongings. Afghan males married to Pakistani women have been deported or forced to return, separating family members.15 In interviews, younger returnees— particularly young men—have reported feeling isolated and disconnected from the communities to which they “return.” The lack of sense of belonging, coupled with restricted livelihood opportunities, may put them at greater risk of recruitment into extremist groups.

Protection and Assistance

International refugee law protects those who have been forced to flee their home country in fear of persecution or violence and whose governments are unwilling or unable to protect them and to provide for their basic human rights. One of the core principles of refugee law is non-refoulement, which prohibits returning a refugee to a territory where his or her life or freedom is threatened. Iran is signatory to the convention. Pakistan is not. However, non-refoulement is international law and binding on all states, regardless of whether they have acceded to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol.

The Afghan government has encouraged safe and dignified return of its citizens. Institutional structures, policies, and processes have been put in place to manage the return and internal displacement, but support for reintegration has been weak.16 Government progress over the past year has been limited, as has coordination between government bodies tasked with policy and programs. The delivery of services and the relationship between central government and provincial governments bearing the burden of the majority of returnees are both weak. The Afghan government has sought to discourage Afghans from migrating to other countries. Although this is a welcome call to action to help rebuild the country, it denies the realities of failed support systems and the bleakness that so many Afghans face on their return.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The humanitarian situation requires immediate attention and effective solutions by the Afghan government at the central and provincial-district levels as well as by the international community. The returnees are the victims of failed diplomacy and political tension between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Afghanistan remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Returnee youth are particularly vulnerable to recruitment by violent extremist groups if they are not properly reintegrated in their communities. Women and girls also face particular hardships that threaten to undo gains on key development objectives. To avoid a full-scale humanitarian crisis, the Afghan government and the international community needs to significantly scale up critical services to the returnees and help stem the flow of those returning.

Improving bilateral relations more generally would be conducive to extending the deadlines for refugees and to limiting the number of people exposed to the impeding humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

Countries deporting Afghans need to reconsider deportation in relation to their obligations under Article 33 of the Refugee Convention on non-refoulement. The numbers of returnees from Europe are small, but European countries could send a strong signal that the principle of non-refoulement must be respected.

Increased political and financial resources should be dedicated to finding durable solutions for registered refugees in Pakistan in recognition of their protracted displacement in the country.

Additional resources—commensurate with the scale of the crisis—are required to assist Afghan government to ensure a better response to returnee challenges. Minimum health, nutrition, water and other basic services must be provided to children and their families as guaranteed through the Citizens Charter program. Additional counseling services for returnees should also be provided.

Afghan government agencies and donor programs need to coordinate their policies and practices more closely. Service delivery programs should include returnees, and target IDP women and girls in particular, as beneficiaries.

Notes

- Mashal Khan Takkar, “Over 7,000 Afghan Refugees Detained in Pakistan,” Voice Times, July 1, 2016, www.thevoicetimes.com/7000-afghan-refugees-detained/; “Pakistan: Coerced Refugee Return Endangers Thousands,” Human Rights Watch, September 14, 2016, www.hrw.org/news/2016/09/14/pakistan-coerced-refugee-return-endangers-thousands.

- UNHCR, “Iran Fact Sheet,” February 2016, www.unhcr.org/en-us/protection/operations/50002081d/iran-fact-sheet.html.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM), “Return of Undocumented Afghans,” Weekly Situation Report: 18–24 December 2016, UN Migration Agency, http://afghanistan.iom.int/sites/default/files/Reports/iom_return_of_undocumented_afghans_weekly_situation_report_18-24_december_2016.pdf; OCHA Afghanistan, “Afghanistan: Returnee Crisis,” Situation report no. 4 (December 2016), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/afghanistan_returnee_crisis_situation _report_no_4_29dec2016.pdf.

- Data for returnees from Iran could be obtained only for January 1 to October 31, 2016.

- IOM’s social and economic survey of returnees from Pakistan finds more than half say that they are in need of shelter. See IOM, “Return of Undocumented Afghans.”

- United Nations Refugee Agency, The 2015 Afghanistan Refugee and Returnee Overview (Geneva: UNHCR, 2015); see also Belquis Ahmadi and Sadaf Lakhani, “The Forced Return of Afghan Refugees and Implications for Stability,” Peace Brief No. 199 (Washington: U.S. Institute of Peace, January 2016); NRC and TLO, “Listening to Women and Girls Displaced to Urban Afghanistan,” Norwegian Refugee Council and the Liaison Office, January 2015.

- Approximately 72 percent of returnees cite Nangarhar as their intended destination. The province has close economic and cultural ties to Pakistan (IOM, “Return of Undocumented Afghans”).

- OCHA, “More than One Million Afghans on the Move in 2016: Record Levels of IDPs and Returnees,” Humanitarian Bulletin Afghanistan 57, no. 1 (October 2016), www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/ocha_afghanistan_monthly_humanitarian_bulletin_october_2016.pdf.

- IOM, “Crisis Looms Amid Skyrocketing Numbers of Afghan Returnees from Pakistan,” September 9, 2016, https://www.iom.int/news/crisis-looms-amid-skyrocketing-numbers-afghan-returnees-pakistan-iom.

- “UN Chief Renews Call for Parties to Protect Civilians,” Press Release, UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, October 19, 2016.

- “Food Security & Agriculture Cluster,” FSAC Bulletin, USAID, July 2016, http://fscluster.org/afghanistan/document/fsac-afghanistan-monthly-bulletin-july.

- “Afghanistan Unemployment Rate: 1991К2017,” Trading Economics, www.tradingeconomics.com/afghanistan/unemployment-rate.

- UNHCR, “Afghanistan: deteriorating displacement crisis requires urgent attention and increased resources,” Display News, October 20, 2016, www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20716&LangID=E#sthash.NrXAgz9N.dpuf.

- “Poverty in Afghanistan,” Asian Development Bank, 2016, www.adb.org/countries/afghanistan/poverty.

- On August 10, 2016, Pakistan’s Interior Minister, Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan told the National Assembly that “the children of Afghan refugees were Afghans and not entitled to the privilege [Pakistani citizenship], even if their mothers were Pakistani citizens” (Iftikhar Khan, “Afghan refugees’ children can’t get CNICs: Nisar,” Dawn, August 11, 2016, www.dawn.com/news/1276821).

- Ahmadi and Lakhani, “Forced Return.”

About this Brief

This Peace Brief updates a January 2016 snapshot of the spontaneous return of Afghan refugees, primarily those from Pakistan, focusing on the humanitarian situation and security implications, as well as the social impact of the mass flow of returnees. Belquis Ahmadi is a senior program officer in the Afghanistan program at the United States Institute of Peace. Sadaf Lakhani is co-founder of Cognitiks, a company applying intelligent analytics to challenges in fragile states and frontier markets.