The Next Five Years Are Crucial for Bougainville’s Independence Bid

Bougainville wants full sovereignty, while Papua New Guinea is unlikely to let it secede. Is compromise possible?

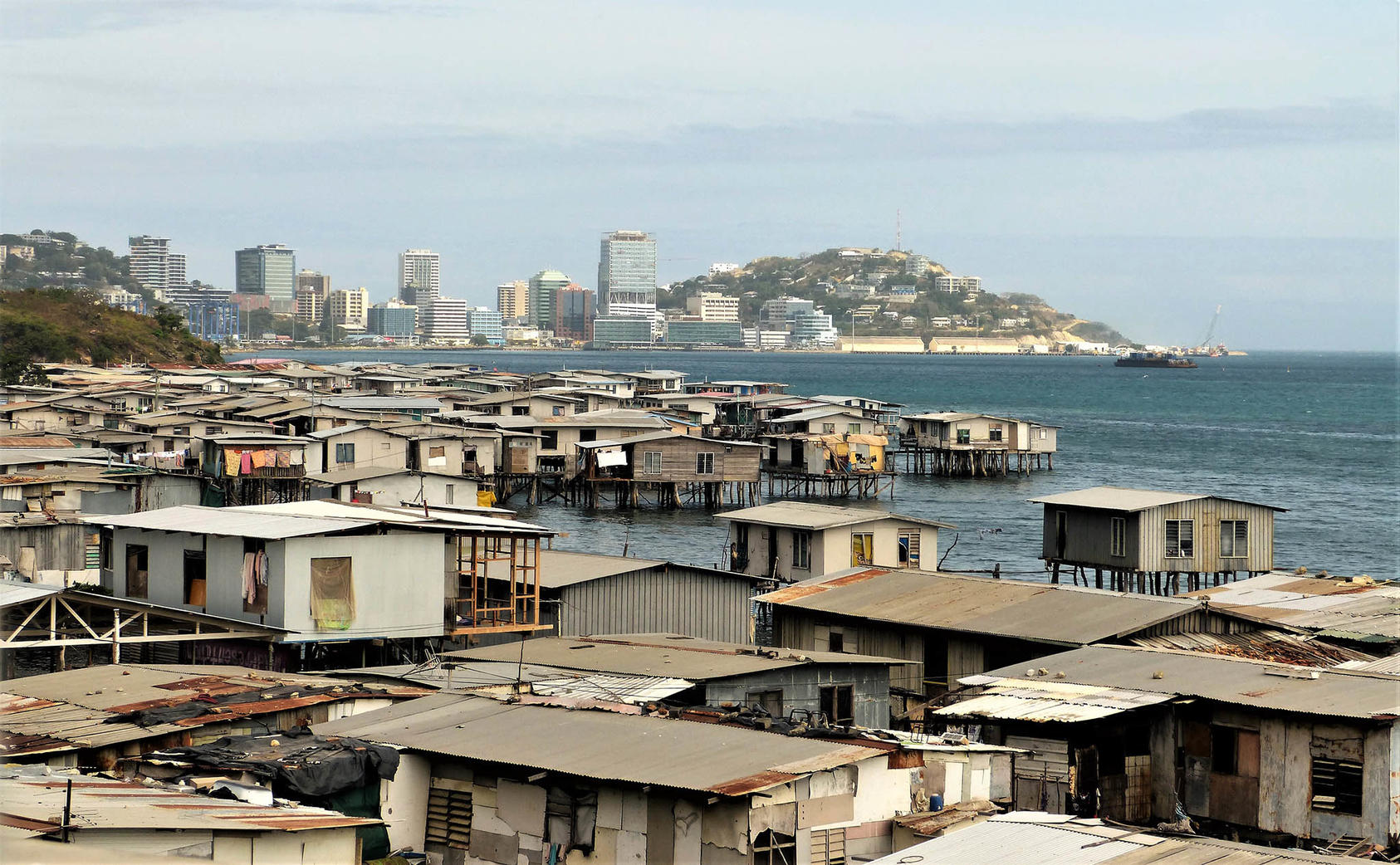

Now that Papua New Guinea Prime Minister James Marape has been reelected, the stage is set for him to settle what he has called the biggest issue facing the country — the future political status of Bougainville, an autonomous region seeking independence by 2027. Papua New Guinea is unlikely to let it secede, but Bougainville is unlikely to settle for anything less than full independence, and positive relations between the two governments will be of paramount importance in the coming years. Meanwhile, intensifying U.S.-China competition in the South Pacific creates wider implications for Bougainville’s potential independence.

Bougainville Has Sought Independence for Decades

Bougainville, an autonomous region within Papua New Guinea, lies to the east of the country’s mainland, north of the Solomon Islands, and comprises two main islands and several outlying islands and atolls. In 1968, when Papua New Guinea was still under Australian control, Bougainville called for a referendum on independence or incorporation into the Solomons, without success. In 1975, two weeks before Papua New Guinea gained independence from Australia, Bougainville declared its own independence, but the motion was disregarded.

The Panguna copper mine — one of the world’s largest open-cut mines and estimated to be worth $60 billion — is central to the independence movement. Mining began in the 1960s, and by the late 1980s, Papua New Guinea’s extraction of wealth from Panguna accounted for nearly half of the country’s exports, while Bougainvilleans themselves made little profit. In 1989, mounting grievances about outside exploitation of the mine and the ensuing environmental damage drove local landowners to sabotage and close Panguna. In response, Papua New Guinea sent military forces to reestablish control, sparking a decade-long civil war known as “the crisis.” In 1990, Bougainville again declared independence during the war.

The crisis was the largest and deadliest conflict in Oceania since World War II. The fighting, along with Papua New Guinea’s military blockade of Bougainville, led to the deaths of up to 20,000 Bougainvilleans — what was then 10 percent of the local population — with thousands more still missing. Its effects are still felt by the “lost generation” whose lives were disrupted by the violence.

In 2001, the two sides signed the Bougainville Peace Agreement, which guaranteed Bougainville greater autonomy, required that an independence referendum be held by 2020 and mandated that the two governments hold consultations on the result. The referendum, which took place in 2019, saw 87.4 percent turnout, with independence receiving an overwhelming 97.7 percent of votes. The other option on the ballot, greater autonomy, received minimal support.

Bougainville and Papua New Guinea Leadership at Odds

But even with the nearly unanimous referendum, independence is far from guaranteed. As the two sides negotiate in the coming years, the risk of stalled negotiations and mismatched expectations is high.

First, the referendum result must be ratified by the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea to take effect. However, parliament is unlikely to ratify the vote, fearing that Bougainville’s secession could lead to other provinces breaking away — including outlying islands and resource-rich highland regions that are already difficult to govern from the capital.

Marape, who will continue to lead Papua New Guinea’s side of the consultations, has not committed to independence for Bougainville, instead encouraging economic independence. “My responsibility is to preserve the union of the country,” he said last year.

Bougainville President Ishmael Toroama, a lifelong champion of independence, leads the other side of the consultations. Toroama joined the Bougainville Revolutionary Army at 19, became a commander during the civil war, and was later an advocate in the disarmament and peace process that led to the 2001 peace agreement. His election two years ago — in an unusually crowded race of 25 candidates, following on the heels of the decisive referendum — was a clear indication that Bougainvilleans want a leader who will deliver them self-determination.

After winning the presidency, Toroama proposed a timeline of two to three years for Bougainville to achieve independence, but last year, he and Marape agreed to a political settlement no later than 2027. Toroama’s willingness to compromise is encouraging, but neither he nor the people of Bougainville are willing to delay independence indefinitely. In another light, the fact that Toroama has already made a significant compromise may make him less likely to do so again.

Meanwhile, there is a concerning disconnect between the two leaders’ understandings of existing agreements. Toroama has reiterated in recent months that the two governments have established a timeline for Bougainville’s independence no later than 2027 — but Marape believes the 2027 deadline is for a settlement, not necessarily independence. He has stated multiple times that independence is only one of several possible options and must still be ratified by the Papua New Guinea parliament.

Bougainville’s Patience May Run Out

A return to civil war does not seem likely or imminent. But if Papua New Guinea is uncompromising and Bougainvilleans become increasingly frustrated with the slow pace of consultations, it may raise the risk of instability in Bougainville. If consultations break down entirely, Bougainville may unilaterally declare independence for a third time.

Toroama’s patience, and the patience of Bougainvilleans, has already been tested. The first consultation took place more than a year after the referendum. In late 2021, Toroama said that independence was being impeded by red tape and that Papua New Guinea was failing to honor the peace agreement. He pleaded with Marape to let Bougainville go, saying that negotiations had gone as far as they could.

Nevertheless, the two leaders signed the Era Kone Covenant in April, which lays out how the referendum result will be submitted to Papua New Guinea’s parliament for ratification, and Toroama praised Marape’s commitment to the peace process.

Toroama is certainly aware of the roadblocks, but his words and actions indicate strong confidence that Bougainville will achieve independence. He has already begun the process of drafting a new constitution, and in April he announced his intention to ask Papua New Guinea’s parliament to ratify the referendum result as soon as next year. In July, he stated that the recent national election would be the last that Bougainville will participate in.

In May, while launching the constitutional commission, Toroama stated, “We must never compromise our resolve for an independent Bougainville and settle for anything less than what we voted for in the 2019 Referendum.” In July, urging Papua New Guinea’s parliament to ratify the vote, he said, “We have fought and died for independence, we made peace for independence and we unanimously voted for independence in an internationally recognized referendum. It is our divine right and we will have nothing less than independence for the people of Bougainville.”

Toroama is signaling to Papua New Guinea his commitment to achieving independence. This is likely creating high expectations in Bougainville, which may be dashed if Papua New Guinea’s parliament refuses to ratify the vote.

Bougainville Likely to Be Drawn Into Regional Geopolitics

Whether a compromise is possible remains to be seen — and independence may be years away. But Toroama is most likely already considering how to sustain the statehood of an independent Bougainville.

His government will need to double or triple its current budget — an impossible task without international aid. Panguna mine, which has been closed since 1989, is regarded as Bougainville’s best economic prospect, but reopening it could take a decade and would be fraught with complications stemming from its history. In 2021, Toroama’s Cabinet established a ministerial committee to cultivate international support and seek U.N. membership.

Bougainville will also need international recognition — and Beijing and Taipei may ask Bougainville to reciprocate that recognition. In 2020, Taiwan sent Toroama a letter of support after his election, offering training, scholarships, medical assistance and development funds. In 2019, China offered to construct airports, highways, bridges and other facilities in Bougainville, and the Chinese private sector showed interest in developing the islands’ natural resources. In 2018, it was rumored that a Chinese delegation had offered funding to help finance Bougainville’s transition to independence.

Bougainville’s dire need for foreign aid could render it vulnerable to China’s influence as it struggles to become the world’s newest democracy — and Bougainville could also become the target of Beijing’s strategic aims. China has sought military access to Papua New Guinea’s islands in the past, and recently signed a security pact with the nearby Solomon Islands. Bougainville occupies a similarly strategic location on regional sea lanes and once hosted multiple World War II military bases. Papua New Guinea would lose its control over the defense of an independent Bougainville, raising the risk that China could seek military access there.

To date, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and the United States have been cautious about taking a stance on Bougainville’s political future, which they view as an internal matter for Papua New Guinea. However, given the precarious nature of an independent Bougainville and the potential strategic stakes, the four countries should pay close attention to Bougainville in the coming years and think through the implications of various potential outcomes.