South Sudan: From 10 States to 32 States and Back Again

What lessons can be taken from South Sudan’s experience of boundary and state management?

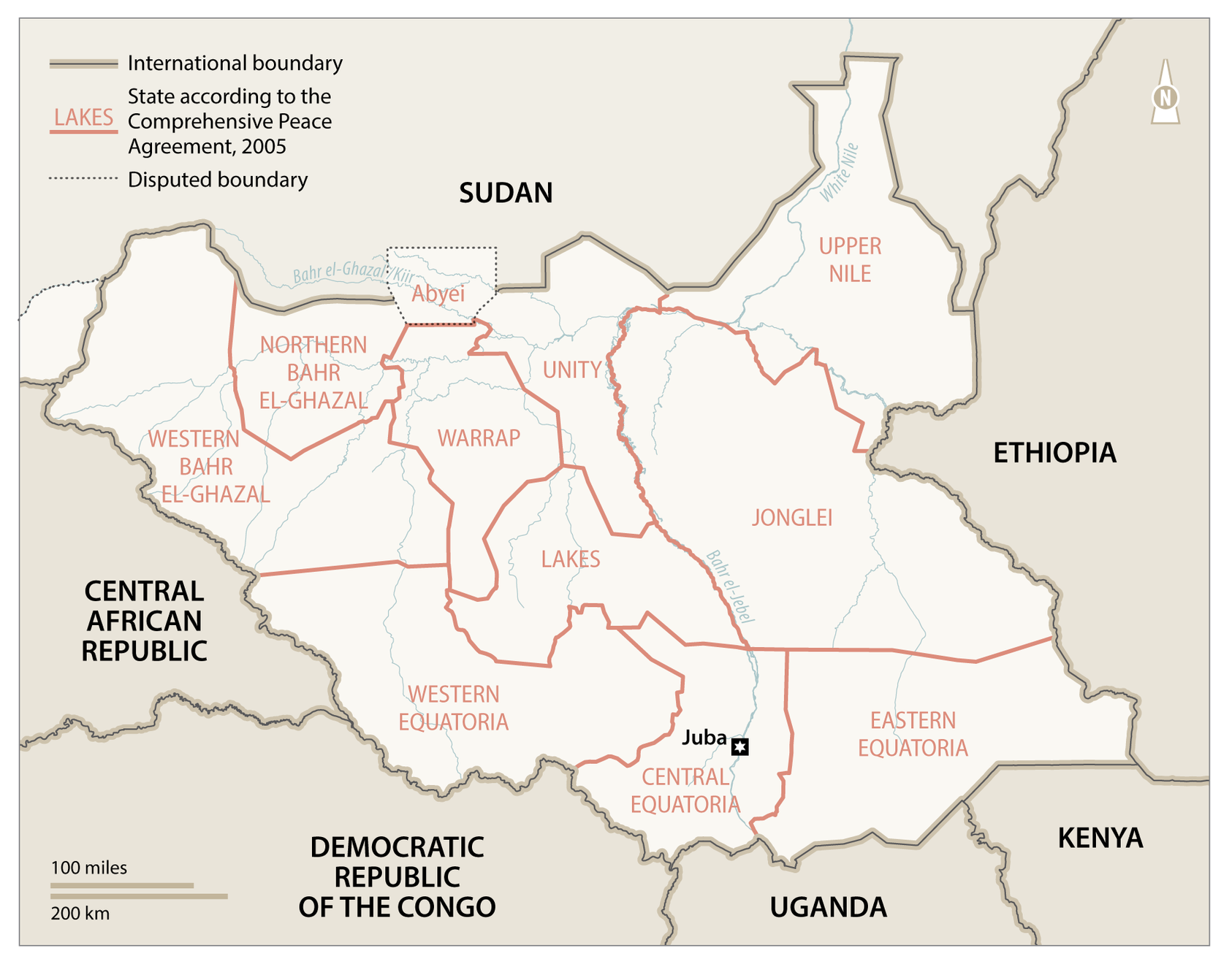

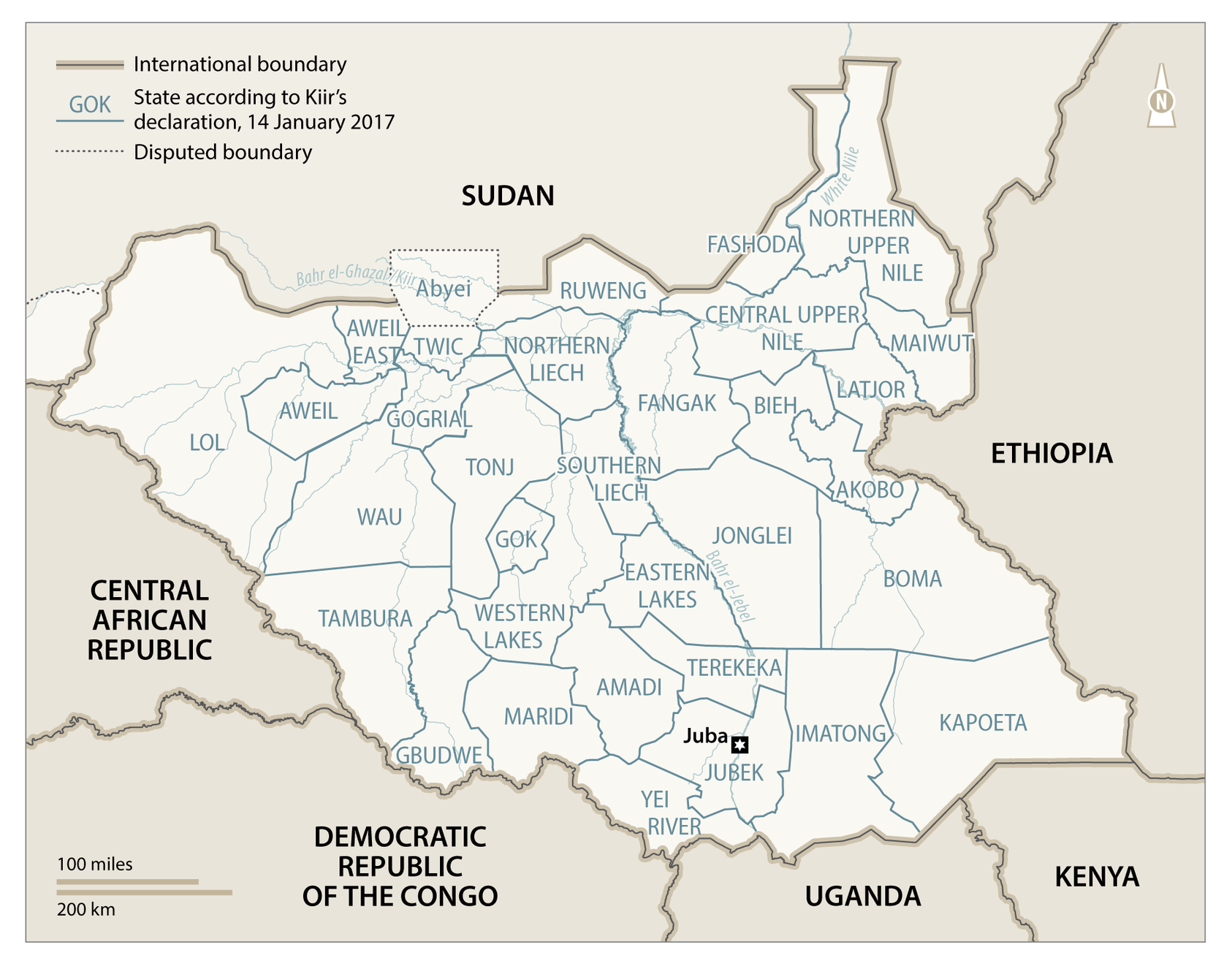

Last year, South Sudan reintroduced 10 subnational states in South Sudan, in place of the 32 states controversially created in 2017. Far from being an obscure matter of administrative organization, the initial, dramatic redivision of territory in the midst of protracted violence and large-scale displacement had a significant impact on representation, as well as social, economic, and political relations throughout the country. In 2018-19, researchers commissioned by USIP sought to better understand the decision-making process behind the creation of the 32 states in South Sudan. Researchers Matthew Pritchard and Aly Verjee discuss their findings in light of current developments.

Why was the creation of 32 states controversial?

Pritchard: Although the reorganization of administrative boundaries is not a new phenomenon in South Sudan and dates back to the colonial period, the justification and impacts of the creation of the 32 states presented new challenges to political and economic ordering. Complex histories of migration, intermarriage, and boundary-breaking were purposefully reduced to and expressed as exclusionary claims to administrative and natural resources. Yet at the time, some ethnic communities welcomed the new boundaries, which they believed would increase their representation at the state and national level and translate into greater control over administrative and financial resources. Other ethnic communities viewed the new states as further evidence of the government’s desire to undermine political and economic reforms and as the consolidation of power in the hands of a military and political elite. In a November 2018 survey of South Sudanese citizens, 75 percent of respondents opposed the decision to create 32 states, noting the dangers of boundary disputes, the risks of undermining national unity, the lack of viability of smaller states, and the unconstitutional nature of the new states.

Verjee: The 2015 and 2017 creation of first 28, and then 32, states disrupted the intended state-level power-sharing arrangements of the peace agreement then in effect. The subsequent peace deal, the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, also provides for power-sharing at the state level. After much delay, new governors were appointed, although whether gubernatorial appointees are sufficiently autonomous from the central government or can govern effectively are open questions. However, irrespective of whether 10, 21, 23, 28 or 32 states (all of which have been mooted) are on the map, disputes over land and the authenticity of sub-national boundaries are almost certain to continue. The National Dialogue Steering Committee Final Report published in December 2020 shows that the issue is far from politically settled: it notes that many South Sudanese call for the “establishment of 32 states and more,” with the view that this will help improve decentralization and the flow of resources to “the towns and villages where the people live.”

What does your research tell us about contemporary and potentially future boundary disputes?

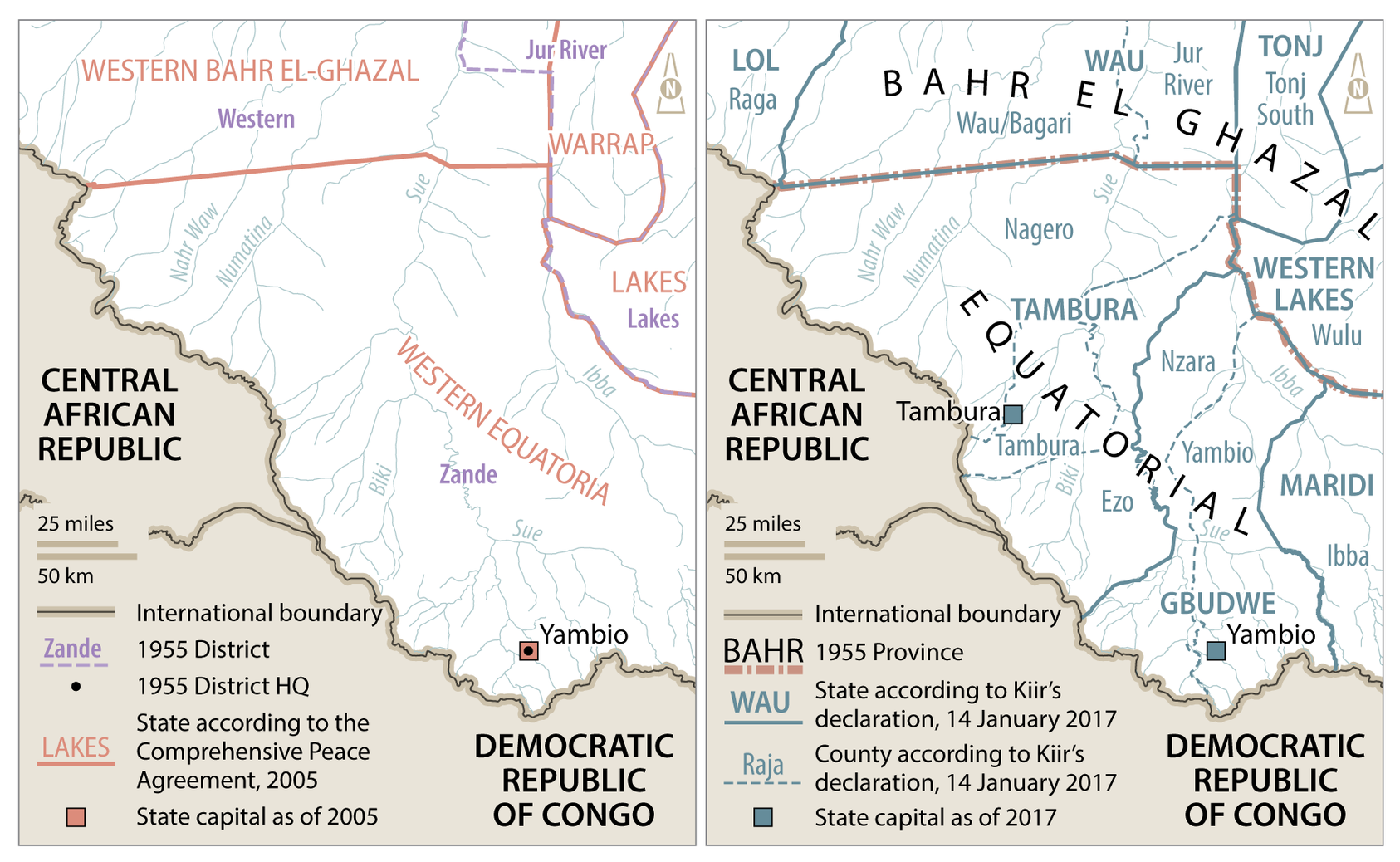

Pritchard: The purpose of my research was to understand how and why decisions about the number of states and their boundaries were made. Widespread belief in and reference to clearly defined and delimited colonial boundaries capable of resolving contemporary conflicts is a common theme across boundary disputes in South Sudan. However, there is no map of district boundaries at the time of independence from colonial administration on January 1, 1956, as the task of surveying and mapping the whole of Sudan had not been finished by the time the colonists withdrew. While the most recent maps before independence date from 1955, these do not answer all questions of where boundaries were.

We should question the practical relevance of using the district boundaries of January 1, 1956 to address contemporary disputes over administrative and political constituencies in a context characterized by widespread and ongoing displacement. Even the most cursory analysis of archival records demonstrates that the states created from 2015 onwards have little to do with historical occupation and administration and that the principle of historical territorial precedent rooted in the maintenance of district boundaries of 1956 has not been consistently applied. The common attempt to link contemporary administrative areas to the former colonial district boundaries has little to do with historical precedent but has become an effective tool for organizing and communicating group behavior around contemporary political and economic claims.

While historical precedent can shed light on specific territorial claims, it cannot alone resolve disputes linked to contemporary competition for access to political and administrative resources. Although recent disputes over the number and boundaries of states are organized, justified, and communicated around narratives of autochthony and length of occupation, they are not about historical precedent or rights, but competition over power and political ordering in a fluid context. Highly ahistorical narratives of autochthony and of primordial ethno-territorial homelands have emerged to solidify access to political constituencies and the resources that flow from administrative control. The resulting increase in the association of ethnic and clan-based communal identities with administrative units, such as states, but also sub-state units such as counties, payams, and bomas, incentivizes competition between newly territorialized ethnic groups, while simultaneously increasing fears of marginalization and exclusion. The result is a zero-sum game where historically interdependent communities with overlapping rights compete for exclusive access to administrative resources in order to control the political and financial power that flows from them.

How have these concerns played out in practice?

Pritchard: Consider Western Equatoria, which was divided into the three new states of Amadi, Maridi, and Gbudwe in 2015, before Gbudwe was split into the two new states of Gbudwe and Tambura in 2017. The Gbudwe state created in 2015 follows the general boundaries of the Zande district at the time of Sudan’s independence from colonial administration in 1956. However, the creation of Tambura and Gbudwe states in 2017 departs from the 1956 boundaries, instead following the general boundary between the former sub-districts of Tambura and Yambio prevailing in 1956. Since the boundary between Yambio and Tambura sub-districts was never mapped or described in detail, it cannot be concluded that the 2017 state boundary is the same as the former sub-district boundary of 1956. The most detailed cartographic approximation found is from 1966, which depicts a boundary between Tambura and Yambio, albeit one significantly different from the 2017 state boundary.

If the motivation and justification for new states was to recreate the districts at the time of independence in 1956, the creation of Tambura and Gbudwe in 2017 does not follow historical precedent. Rather, it appears that the 2017 division of Gbudwe was a political decision meant to address historically rooted and ongoing divisions between the Azande clans of Tambura and Yambio. The majority of key government positions in Zande district and Western Equatoria have traditionally gone to Azande from Tambura. It seems, therefore, that unequal access to administrative resources led the Azande of Yambio to complain of political and economic marginalization and demand their own administrative area. Where this is a lack of representation and socioeconomic services, geographic and clan-based divisions have emerged as the primary way to access administrative and economic resources. In this case, historic and ongoing inequality between Azande clans is not associated with corruption or a lack of accountability, but the fact that a given clan (i.e., the Azande from Yambio) is not effectively represented in the state government.

Having returned to 10 states, what lessons can be taken from South Sudan’s experience of boundary and state management?

Pritchard: In a context characterized by an almost complete lack of services and downward accountability, communities increasingly view ethnic- or clan-based identities as the only way to ensure access to resources and physical security. Economic incentives driven by the changing value of land reinforce the political value of holding territory, leading historically interdependent communities to draw increasingly stark distinctions between “insiders” and “outsiders.” These demands and incentives do not disappear even if South Sudan is organized in 10 states rather than 32.

Verjee: In the 10 years prior to 2015, governance of South Sudan’s 10 states was shaky at best. Most state governments have little to show for those years. Some governors were more notably causes of instability and insecurity rather than contributors to peace and prosperity. The governors now in office would do well to consider the legacies of their predecessors as they plan for the future. Ultimately, this long journey to create and then consolidate states in South Sudan leaves many citizens where they were before: wondering what the state can and will do for them, and whether long-standing patterns of exclusion, insecurity, and poverty will one day be broken.

Matthew Pritchard is a research and policy specialist focused on land tenure reform, housing, land, property, and boundary disputes in conflict-affected environments.