Pakistani Police Women Examine Unique, Common Obstacles in USIP Visit

Seven women from Pakistan’s police forces explored the unique obstacles they face, such as the debate over all-female police stations in their country, during a recent visit to USIP.

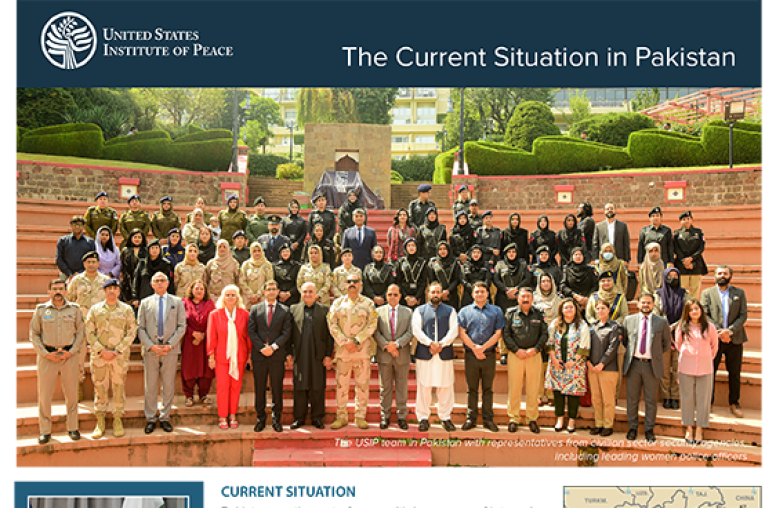

Seven women from Pakistan’s police forces explored the obstacles they have in common with their American counterparts and those that set them apart, such as the debate over all-female police stations in some parts of the country, during a visit to USIP in December. The session was part of a week-long study tour organized by the U.S. State Department that included time with American police forces in a search for lessons they can apply in their own work.

In addition to handling traditional policing duties, Pakistani police are the front line in combating terrorism, civil unrest, and organized crime. According to the visiting delegation, the police are expected to perform a wide range of job functions with very few resources, often in dangerous circumstances. They typically work long days, up to 18-hour shifts, with little time off for holidays or personal leave, and they receive significantly less training than their American counterparts.

These factors, along with shortfalls in equipment and technology, make Pakistani police ill-equipped for many of the situations they face. Furthermore, police work is complicated by the history of abuse by police in Pakistan, so residents may be reluctant to cooperate with them. Police officers are often perceived as corrupt, ineffective and even as a potential security threat. They are also prime targets of violent and often deadly attacks perpetrated by extremist elements. In addition to the broader challenges of policing in Pakistan, female officers face obstacles related to the shifting cultural roles of women in society. Some police districts have created special all-female stations to handle cases involving women. In other, regular stations, women officers shadow male counterparts and handle cases directly involving women in an effort to better integrate forces by gender. Such initiatives offer an alternative to traditional arrangements that sometimes relegate female officers primarily to office tasks that limit room for advancement.

Separate women’s police stations may serve the community better by making female citizens more comfortable interacting with the police. Some female officers said they were uncomfortable having a male supervisor and felt more comfortable working in an all-female station.

Additionally, all-female stations allow female police officers broader opportunities to undertake all of the same work done by their counterparts in other stations. In the course of their duties, these women then interact with their male counterparts as equals.

On the other hand, maintaining separate male and female stations risks creating an unequal level of police services for men and women. Currently, all-female police stations exist only in some major cities. This can make the distance to reach the appropriate station prohibitive for both female officers and civilians. It can also significantly complicate handling of a complaint if a crime involves both men and women.

In addition to these structural constraints, female police officers must work in a society where women face further cultural and political restrictions. While Islamabad is more progressive, in many of the outlying areas of Pakistan, aspiring to be a police officer may not be socially acceptable for females. Young women are discouraged or even forbidden by their male relatives from applying for the force. Low levels of female education make finding qualified candidates challenging.

When applying to become a police officer, the number of slots available for women is small, regardless of how well female candidates fare on the entrance examination. Once female candidates are accepted to the police academy, they must overcome social stigmas against women in the security sector and balance a demanding job with their more traditional roles in the home.

All of these obstacles have resulted in very few women successfully entering and staying in the police force.

Advancement for female officers is also a challenge. Male and female officers are given the same training at the police academy. However, upon graduation, women are often assigned to desk jobs or other administrative duties.

Due to the resulting lack of field experience, such postings prevent women from being considered for promotions and other opportunities to advance their careers. When women are promoted, they often are not awarded the same job responsibilities as men. In some cases where women have pushed for additional responsibilities that should accompany a position, they may instead be transferred to an area with less responsibility.

Despite the challenges they face, it is clear that female officers can make unique contributions to policing in Pakistan. They can act as natural liaisons between the police force and the community and are able to interact with entire sections of the population that male police officers are unable to reach. Female officers act as conduits between the police and civilian women and are able to approach women in their homes, which can provide a unique insight into criminal activities. This has positive implications for increasing police effectiveness, strengthening civilian-police relations, and fostering cooperation.

An additional benefit is that successful female officers act as role models for the next generation of police women and encourage Pakistani women in general to pursue their chosen professions.

Several things can be done to help women in the police force, the USIP visitors said. First, female Pakistani police have called on parliament to reserve 10 percent of slots in the police academy for women and minorities. Similar quotas are being put in place for federal jobs and public sector employment.

Second, all Pakistani officers, particularly women, need additional training in weapons, driving, forensics and technology. One member of the delegation estimated that it takes 10 Pakistani officers to accomplish what one American police officer can do because of their lack of access to technology and training. In regards to training, there is room for more gender sensitivity courses for male officers that highlight the value added by their female colleagues.

The Dec. 10 roundtable highlighted many of the issues faced by Pakistani police and the particular challenges confronting female officers. The police force in Pakistan is tasked to undertake great responsibility with very little capacity. Women, in particular, must overcome great obstacles to be successful police officers. The leaders in the delegation said they exemplify the positive impact that women can have when they obtain meaningful positions within a police force.

Shannon Zimmerman is a Boren Fellow in USIP’s Center for Gender and Peacebuilding and Emily Horin works in the Institute’s Center for Conflict Management.