The Global Gender Gap Index ranked Pakistan in 2016 as the second lowest country in the world for gender equality. Women’s political participation is recognized as an essential component of gender equality and in Pakistan the gender gap in participation is particularly high. Ensuring gender equality in political participation matters: A recent survey conducted by these authors finds that, at least in some public policy domains in Pakistan’s big cities, the issues that matter to women are different from the issues that matter to men. This demonstrates that greater gender equality in electoral participation could substantively change what issues are represented in the political arena.

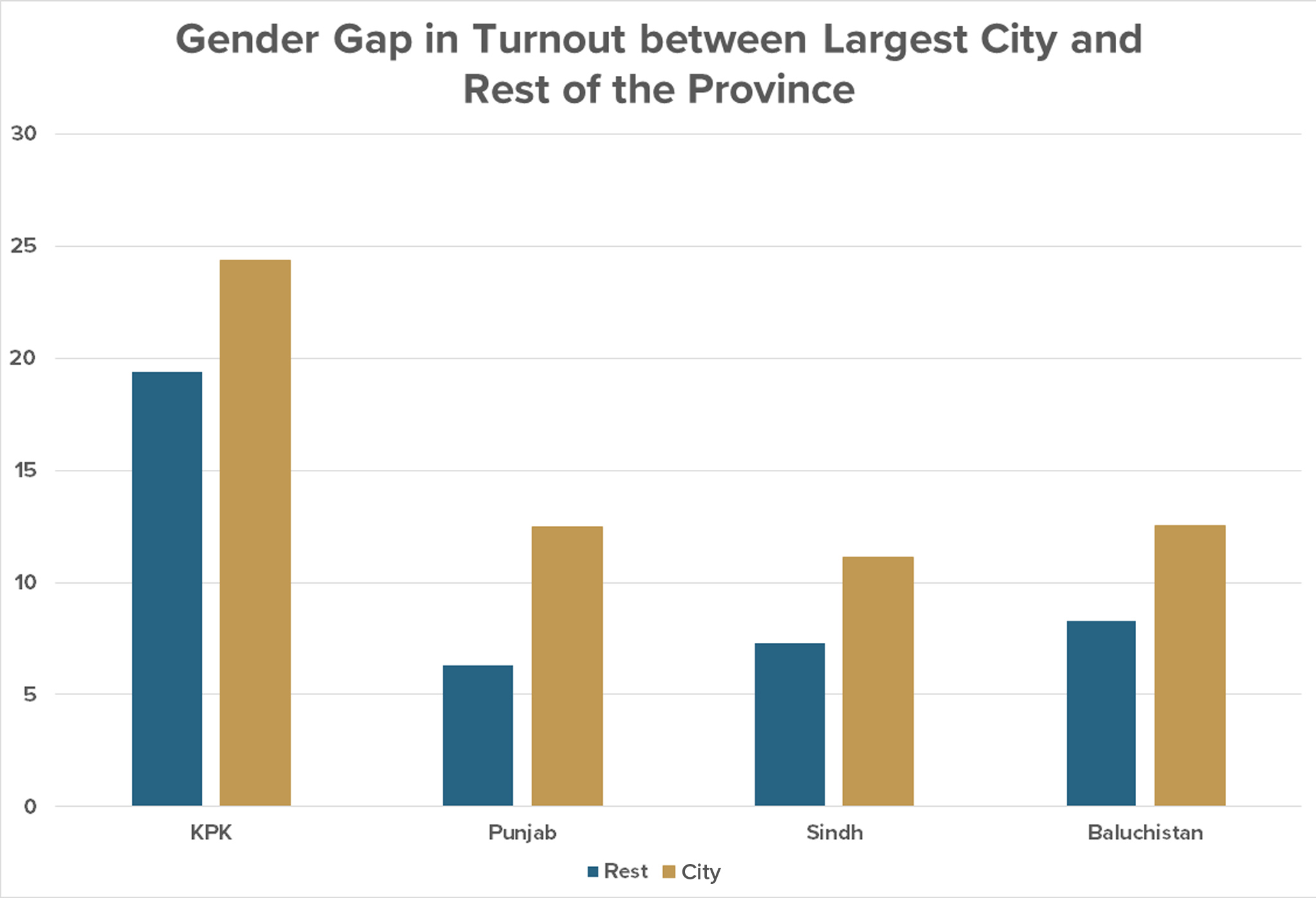

In Pakistan’s 2018 general elections, the male-female gap in voter turnout stood at 9.1 percent with 11 million fewer women exercising their right to vote than men. It is generally assumed that a high gender gap in turnout is due to communal customs in rural constituencies and that in metropolitan areas local elites and political actors rarely suppress female voting. Through our research, however, we found a larger gap in metropolitan cities than in rural constituencies.

Looking at turnout data from 2018, there is a much higher gap in the largest metropolitan cities compared to each province’s remaining constituencies. The difference between the largest metropolitan city and the rest of the province is highest in Punjab, with the gender gap in turnout in Lahore being double (12.5%) that in the rest of the province (6.3%).

Women’s Turnout Matters

This disparity between cities and rural communities is particularly important because population growth in Pakistan’s larger cities is significantly greater than in the rest of the country. Women are an important constituency for the provision of clean drinking water and curbing inflation with 18.3 percent and 16.1 percent respectively citing these as the most important public policy issues in the run up to the 2018 election, compared to 9.2 percent and 9 percent of men in the sample. This suggests that it is critical that the gender gap in participation is addressed so that women’s concerns are addressed by their elected leaders.

Unfortunately, of the 46 million women that are registered to vote in Pakistan, only 40 percent participated in the 2018 elections. Women face a number of barriers to greater political participation, both societal (e.g., traditional views on a woman’s place in society) and bureaucratic (e.g., lack of access to national identity cards that give women an official record within the system).

These barriers remain despite concerted efforts by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) to register female voters by providing opportunities to obtain their national identity cards in the lead up to the 2018 elections. Additionally, changes to the election law empowered the ECP to void the results in any constituency where the female voter turnout is less than 10 percent of the women on the voter rolls. Nevertheless, the gender gap in electoral turnout remained stark in the 2018 elections.

What Explains the Gender Gap in Metropolitan Pakistan?

We address this question using an original survey of 2,500 randomly selected households in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city with a population of 11 million. Our results show that the gender gap in metropolitan cities is related to patriarchal norms in the household and individual women’s knowledge of politics and the electoral process. Poor knowledge goes hand in hand with women’s low interest in politics, which is unsurprising in a context in which political parties fail to directly engage women and address their issues.

Patriarchal norms: We found that the most important household factor determining women’s participation is men’s views about women’s political engagement and the conditions under which they think it is appropriate for women to vote.

- In our sample, 8.3 percent of men think it is inappropriate for women to vote in a general election. Unsurprisingly, households where men think it is inappropriate for women to vote in elections have an 11 percent lower turnout of women.

- Nearly 55 percent of men in our sample think it is acceptable to prevent women in their household from voting if they vote differently from them. Households where men hold these views had a 4.5 percent lower turnout of women.

- Approximately 43.4 percent of men think it is acceptable to prevent women from voting if there is a chance of fighting breaking out at the polling station. Households where men hold these views had an 8.6 percent lower turnout of women.

This suggests that men remain important gatekeepers in mediating women’s ability to vote and that individual attitudes and social norms upheld by men are an important determinant of women’s turnout in metropolitan cities. This gatekeeping works not through coercion but through the need for women to seek permission from men, and some permissions are more easily granted than others: “Mostly elderly women go out and vote, very few young women go out and vote because a lot of younger women don’t get permission to go,” explained one of our male respondents. This echoed other respondents’ remarks, noting that both security concerns and household work affected younger women’s political participation more than it did older women.

Political knowledge and the mobilization gap: A key determinant of women’s turnout in the 2018 elections was knowledge of politics, elections, and the voting process. Our research shows that the more knowledge women have of the electoral process and of politics in general, the more likely they are to participate at the polls.

Poor political knowledge among women is strongly correlated with low levels of interest in politics and that, in turn, has a strong association with the low contact between political parties and women voters. A common refrain heard from women in our focus groups is that they feel that they are invisible to political parties and that their issues did not matter. As one respondent put it: “Most political party members and workers talk to the men in our families and do not attempt to engage with us. We would appreciate it if someone made an effort to communicate with us women, and if we find some merit in what they are saying, we will support them regardless of the political party.”

Low contact between political parties and women is due to the gendered nature of mobilization by political parties who typically rely on men to mobilize the women in their households. In our sample, 22 percent of women reported that a political party representative had visited their household in the days leading up to the previous general election. Out of these, almost half (47%) reported that the party representative did not attempt to speak to the women in the household. This was much more likely to happen when the party only sent a male representative. The failure of political parties to deepen the base of women workers and leaders is an important facet of the disengagement of women from politics in metropolitan cities.

Policy Recommendations

The gender gap in electoral turnout in Pakistan’s metropolitan cities reflects complex social dynamics and addressing this challenge requires the ECP, political parties and civil society organizations (CSOs) to take concerted action. Such actions include:

- Civil society educational and motivational campaigns are effective at boosting women’s turnout in the metropolitan context. We evaluated a nonpartisan voter education campaign conducted by two reputable CSOs (Aurat-Foundation and SAP-PK) in Lahore before the 2018 general election and found that voter education campaigns have a large impact and increase women’s turnout by 8 percent, provided that the campaign targets both men and women in the household.

- Political parties need to directly engage with women to reduce their perception of being “politically invisible.” It will be difficult for political parties to do so unless they deepen their cadres of women workers and give women greater representation in the pool of candidates that they nominate. It is important for the ECP to create greater awareness among political parties about the importance of women voters for governance as well as their potential to act as pivotal voters.

- Another instrument that may have promise in reducing women’s political invisibility is the institutionalization of women’s collective action groups within neighborhoods that can provide them with public spaces to discuss government performance on public service delivery, and how to make more effective demands for these from their national, provincial, and local representatives.

Ali Cheema is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS), and an associate professor of economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). Sarah Khan is a postgraduate associate at the Yale MacMillan Center and a Ph.D. candidate in political science at Columbia University. Asad Liaqat is a Ph.D. candidate in public policy at Harvard University and a graduate researcher at IDEAS Pakistan. Shandana Khan Mohmand is a fellow and lead of the governance cluster at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex. Anam Kuraishi is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.