On the Issues: Pakistan

President Barack Obama recently met with Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari and Afghan President Hamid Karzai and pressed the two leaders to do more to combat Taliban and al Qaeda fighters in the border area. Rodney W. Jones, program officer for USIP’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention, assesses Pakistan’s efforts to battle insurgents, the Obama administration’s new approach on Pakistan and Afghanistan, and what USIP is doing to address the problems in the troubled region.

President Barack Obama recently met with Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari and Afghan President Hamid Karzai and pressed the two leaders to do more to combat Taliban and al Qaeda fighters in the border area.

Rodney W. Jones, program officer for USIP’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention, assesses Pakistan’s efforts to battle insurgents, the Obama administration’s new approach on Pakistan and Afghanistan, and what USIP is doing to address the problems in the troubled region.

- What is Pakistan doing to combat Al Qaeda and Taliban?

- And where are things now?

- Is the country at risk of falling apart, or failing?

- What resulted from President Barack Obama's meetings with Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari?

- How does Obama's approach differ from Bush's approach?

- What is USIP doing in the region to address and counter these problems you talked about?

What is Pakistan doing to combat Al Qaeda and Taliban?

Pakistan has worked fairly closely with the U.S. against al Qaeda in particular. Pakistanis in the border region talk about the Arabs -- the militant "foreigners" in the region, who also include Chechens, people from Central Asia, such as Uzbekistan. The Arabs who make up the core of al Qaeda come from several states in the Middle East and North Africa, from Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Libya, among others .

Since 2001, Pakistan has picked up, confined and turned over to us scores of known al Qaeda fighters, once they are detected – but it hasn’t been so successful in getting the topmost leadership of al Qaeda, like Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Egyptian.

Pakistan has been less successful in helping the U.S. and the international coalition get Afghanistan back on its feet. What’s hurting that effort is a resurgent Taliban movement attempting to come back to power in Kabul and Kandahar, after the U.S. deposed it in late 2001. Key Taliban leaders fled into the mountainous and relatively inaccessible Pashtun borderlands adjoining northwest Pakistan and the key Al Qaeda’s leaders did too.

The Taliban movement which arose first in 1992 was almost exclusively Afghan Pashtun in make up. The Pashtun peoples are composed of many tribes. Some of those Pashtun tribes regard themselves as the natural rulers of Afghanistan and supported the Afghan monarchy based in Kabul until it was overthrown in 1973 – ultimately setting the stage for Soviet intervention and the decades of instability that led to al Qaeda’s formation and our post-9/11 challenge. The Pashtun have traditionally constituted the largest single ethno-linguistic group in the ethnic mosaic of Afghanistan. However, the Pashtun peoples overlap geographically with Pakistan and are actually greater in number today in Pakistan than in Afghanistan.

Most Pakistani Pashtuns reside today in the "settled areas" under formal federal and provincial governments, and have become well integrated in the Pakistani agricultural and industrial economy. But in the relatively inaccessible mountains forming the tribal region of Pakistan, the traditional Pashtun tribes have enjoyed, and zealously protect, a form of political and cultural autonomy acceded to by the British colonial system and continued by Pakistan since 1947.

These tribal areas and adjoining Pashtun districts of Balochistan – which together hold about one fifth of the Pashtun population resident in Pakistan -- have become sanctuaries for the Afghan Taliban and, more recently, have become the launch pads for the Pakistani Taliban.

The Afghan and Pakistani Taliban followers probably represent at most five percent of the surrounding Pashtun tribal population, but they have imposed and continue to spread their system by force of arms, religious appeals, cellphones and SUVs. It is these tribal areas inside Pakistan that have provided sanctuary, sometimes willingly, sometimes under bribery or coercion, to al Qaeda and the Afghan side of the insurgency. It is in these same tribal areas that the Army of Pakistan is easily ambushed and finds it exceptionally difficult to operate to put down the insurgencies and seal the border.

The Pakistani government, under President General Pervez Musharraf, at first made an honest effort to contain the rising Taliban insurgents and prevent border crossings but they discovered they couldn’t do it very well by themselves.

By 2004, Musharraf was telling us that U.S. forces needed to do a better job on the Afghan side of the border – saying we had all the high tech equipment to monitor and prevent border crossings. It was clear then and in the next few years to Pakistan that U.S. attention was focused primarily in Iraq and the effort in Afghanistan was under-resourced.

By 2007, the Taliban’s resurgence in Afghanistan had become pretty big, and a unified Pakistani Taliban counterpart had also formed and was beginning to expand into the settled areas of Pakistan, particularly the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). And there was a huge spike in casualty rates in Afghanistan among our forces and NATO forces inflicted by insurgents who are able to infiltrate villages and set up ambushes, and who have increasingly adopted suicide bombing tactics in the urban areas and the use of improvised explosive devices along the roads in Afghanistan – learning from terrorist methods in Iraq. They have also been intimidating the nongovernmental organizations with footholds in Afghanistan, seeking to help rebuild the economy, build new schools, and reestablish various commercial ties and get the country back on its feet rather than falling back on growing poppy for opium and heroin.

And where are things now?

Pakistan’s military efforts to counter the Taliban inside Pakistan began to waffle in 2005 and 2006, for two reasons. One, the regular military forces being used – infantry units of the regular Pakistani army – depend on a logistics train with convoys of heavy vehicles, and these were being ambushed. Most of the soldiers in these units are Punjabis, who come from a different region of Pakistan, so they have less in common culturally with the Pashtuns – they didn’t mix so well with them, compromising their ability to get meaningful intelligence and maintain situational awareness. But at the same time, the Punjabi soldiers understood that they were fighting fellow countrymen, and killing Muslims. They were taking hits, and they were fighting people for a reason they didn’t fully understand. As a result, some them really became demoralized, and their reluctance to fight spread up the chain of command. These factors were drivers of the Musharraf government’s efforts to negotiate standstill agreements and peace pacts both with traditional Pashtun tribal leaders (maliks) and with the leaders of the armed Taliban groups themselves.

A second factor in weakening the Musharraf-led Pakistan government’s commitment to pursue counter insurgency vigorously was the political movement against Musharraf in 2006 and 2007, to force national elections and the return of civilian government, and ultimately to throw him out of office personally. That mobilization of urban civil society and mainstream Pakistan did much to crystallize the anti-American shift in public opinion, giving momentum to the view that fighting insurgents in the Pashtun region of Afghanistan was really America’s war, and not Pakistan’s responsibility. Large sectors of the Pakistani public came to believe -- short-sightedly – that the Taliban and other militant groups in the Pashtun borderland would stop fighting if the U.S. stopped fighting. And, that led to a loss of support for the U.S. objectives of rooting out al Qaeda and its affiliates in the region. The Pakistan Army had become quite ambivalent about this problem, doubting the U.S. and coalition capacity to prevail, ultimately, against the Taliban and bring order and stability to Afghanistan.

Amid all the political turmoil, the Pakistani military has not been very effective in counter-insurgency, it hasn’t been trained in or equipped for counter-insurgency -- and the insurgency has spread in 2008 and 2009 like molasses. The post-colonial methods of maintaining peace in the tribal areas have broken down. The Pakistani military believed they could continue to employ those methods. But once the traditional approaches broke down, they had no ready-made alternatives.

The Taliban insurgency and offensive by allied extremist groups now has gone beyond the so-called tribal areas and into the settled regions of the North-West districts, like Swat, Shangla, Malakand, and Buner – regions fairly close to Islamabad, the Pakistani capital.

The insurgents were getting closer to the base of the federal government, which was trying to appease the insurgents. But, it is now gradually becoming apparent that the appeasement approach could not work because these are clearly people who will not be appeased. The military didn’t have bases in such formerly peaceful areas as Swat and Malakand; they didn’t need them before. So now the military has to build infrastructure, as well as build up forces, in order to reestablish control by means of force.

What’s happening today is there’s a gradual hardening of Pakistani political and military elite attitudes that appeasement has failed, and unless the country acts in a unified way to stem this insurgent tide, the country would be increasingly encroached upon by a radical Islam. But it is not clear yet that this elite realization will be transformed into effective courses of action.

Is the country at risk of falling apart, or failing?

I don’t see a risk of the country falling apart, or splitting apart. But there is some risk of Pakistan turning into a crisis-ridden country without any mainstream consensus on its national purpose, a country that is inhospitable to the normal path of modernization and unable, due to intimidation by Islamic extremists, to preserve its formerly moderate Islamic vision of society. If that occurs, Pakistan’s hoped for role as a bastion of moderate Islam and a moderating influence among the Muslim countries as a whole, and particularly in the Gulf and Mediterranean regions, will be impaired.

My best guess is that the Pakistan will gradually right itself and cope with these challenges. But this may take some time and our ability to partner effectively with Pakistan on stabilizing Afghanistan may not be smooth. What is clear is that for the last two years Pakistan has not been going in a direction compatible with our interests. The Bush administration came around to actively supporting democratic elections and a return to civilian rule in Pakistan. But it is also a sad reality that the elected political leadership of Pakistan has not gotten its act together. It needs to rally public opinion against the spreading militancy and define it clearly as a danger to the nation. Then it needs to develop a strategy and a solid, concerted long term effort to deal with it.

What resulted from President Barack Obama's meetings with Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari?

The main result of President Zardari’s meetings with President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been twofold, an acknowledgment by Zardari that Pakistan indeed faces a profound threat from the spread of militancy, and a reaffirmation by Obama of U.S. support for democratically constituted government in Pakistan. The Obama administration is pledged to provide Pakistan with broad economic support as well as appropriate military assistance.

Obama took a nuanced position on both Asif Zardari and Afghan President Hamid Karzai. He urged both leaders to step up to the plate and indicated that the U.S. is solidly behind their governments if they do. Obama is making it clear it wants to actively support a democratic government in Pakistan and supporting democratic elections in Afghanistan. But he’s also made it clear that the U.S. doesn’t want to be tied to supporting personalities – so it’s not about supporting Zardari or Karzai, but supporting the governments of both countries.

At the same time, Obama’s people have made it clear implicitly that the U.S. does not in any way favor the military returning to power in governing Pakistan.

How does Obama's approach differ from Bush's approach?

One major contrast behind the Obama-Holbrooke [Richard Holbrooke, U.S. Special Representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan] approach and the Bush approach is the funding. Earlier, under Bush, our military assistance and funding for Pakistan was roughly ten times the size of what we were providing in non-military assistance.

Today that is being rebalanced. The military assistance will be sustained, but it will be outweighed by a larger economic package for reconstruction and development, and to help promote the economies of the tribal areas. It’s geared to help Pakistan modernize, which means public health initiatives, women’s literacy, energy infrastructure.

There was very little of that happening during the Bush administration.

Now, we’re spending $800 million a year for the military side, and $1.5 billion for the economic, social and development side.

What is USIP doing in the region to address and counter these problems you talked about?

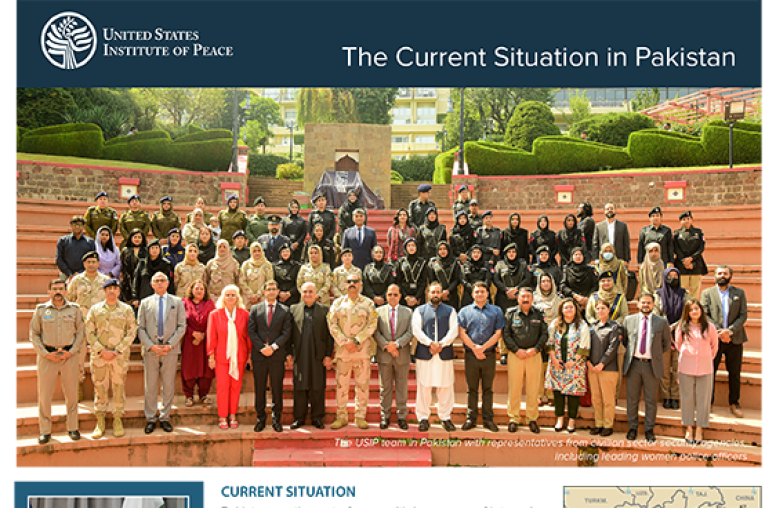

Right now, we have much more going on in Afghanistan than Pakistan. Our work in Pakistan has been limited but will be growing. On one front, currently, we’re helping to strengthen Pakistani society and governance by developing networks of conflict resolution practitioners. One of the channels focuses on women professionals, another channel focuses on parliamentarians. We have also had projects underway on religion and peacebuilding, with the production by Pakistani partners of a textbook on Islamic principles of conflict-resolution, working across sectarian lines.

This is hugely relevant to have Pakistanis getting into mediation and conflict resolution, learning the skills to bring culturally diverse people together. The country needs its people to move it in the right direction as whole. And, right now, there’s not a lot of certainty where that country is heading, even at the highest levels.

On another front, we’re providing intellectual analysis and leadership to help U.S. policymakers and the American public understand what’s going on in Pakistan, and how to have a constructive relationship with Pakistan.

We may be able to expand our strategy in a way that complements the Obama administration’s Afghanistan-Pakistan (AFPAK) strategy in cross-border programs in the Pashtun regions of both countries.

The views expressed here are not necessarily those of USIP, which does not advocate specific policy positions.