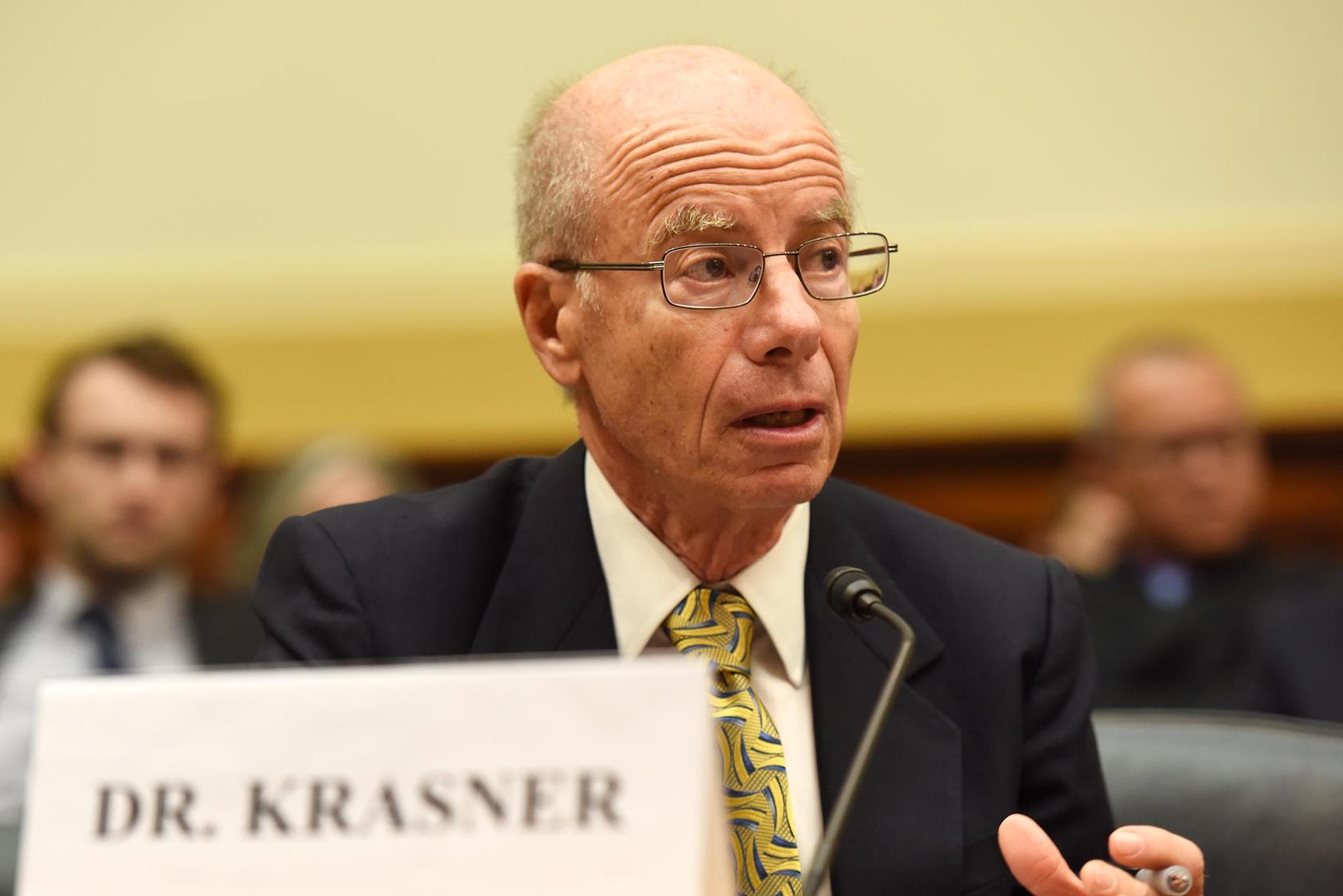

Stephen D. Krasner Testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs

Chairman Royce, Ranking Member Engel, and other distinguished members of this Committee thank you for the opportunity to testify before you this morning.

The United States has been the leader in the post-World War II international order. This order has not been perfect but it has ushered in the longest period of peace among the major powers that the world has ever seen, growing levels of economic prosperity in many parts of the world and the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union itself. The United States has benefitted from this global order and others have as well. Indeed, if the American led order were not generating benefits for many, we would not have had the kind of support that we have enjoyed over the last 60 plus years. The more than 30 countries that fought with the United States in Iraq, and the even larger number that supported us in Afghanistan, are testimony to the support that the United States has received. If the United States withdraws from the global system, there will be a vacuum. The most likely countries to fill that vacuum, China and Russia, do not share our rules, norms or values.

American engagement and our national security require that we use all three critical tools in our arsenal: defense, development, and diplomacy. Losing any one of these instruments of national power would threaten the security of the United States and the global order from which we have benefitted.

Poorly governed, failing, or weak malign states pose three threats to the United States and our core allies. The first is transnational terrorism. The second is a pandemic disease outbreak. The third is massive migration.

Terrorist attacks can arise from anywhere. The husband in the San Bernardino murders, Syed Farook, was raised in the United States and attended California State University Fullerton. But he was inspired by ISIS ideology. Failed and badly governed states provide safe havens for radicalized Salafist Islamic groups such as ISIS and Al Qeda; places where they can train adherents, propagate their message, and refine their ideology. These groups and the individuals they inspire are a direct security threat to the United States. This threat has been amplified by the fact that nuclear or dirty nuclear weapons might be secured from failed, malign, or badly governed states and that biological pathogens can be more easily fabricated by individuals or groups.

Naturally occurring pandemic diseases are a second threat. About 400 diseases have jumped from animals to humans over the last 70 years. Most of these diseases have originated in tropical areas where human populations are impinging on areas that had previously been populated only by animals. Up to now we have been lucky. The most well known of these diseases, HIV/AIDs and Ebola, have been difficult to transmit. A disease that was however, transmissible through the air instead of via bodily fluids could kill hundreds of thousands or millions of Americans. Stopping these diseases when they first break is our best line of defense.

Finally massive migration threatens liberal and humanitarian values. European states have been most afflicted by the massive displacement of people from wars in the broader Middle East. There are no good policy options to address such movements once they begin: accepting unlimited numbers of individuals is untenable; sending refugees back to unsafe countries could bring a humanitarian catastrophe. Our best policy option is to prevent such flows in the first place.

One half of the dilemma that the American government faces is that we ignore badly governed, failed, and malign states at our peril. If states are reasonably well governed, at least if they have adequate security, terrorism, potential pandemic diseases, and massive migrant flows could be better contained. If states are weak, failing, or governed by malign autocrats our security challenges will be greater.

The second half of the dilemma that the American government faces is that it is very difficult to put countries securely on the path to democracy and a market oriented economy. The rich democratic countries of North America, Western Europe, and East Asia are, historically the exception not the rule. For almost all of human history in all places on this globe government have been rapacious and exploitative. There was no accountability for political rulers. Power flowed from the barrel of a gun or the tip of a spear or the string of a bow. Political rulers fed their cousins and those who commanded the weapons that they needed to stay in power. Governments that occupy the Madison sweet spot, governments that are strong enough to maintain order but accountable enough to not oppress their own people are the exception not the rule.

There is no natural progression from poverty to prosperity, from autocratic rule to democratic rule. For the most part, countries that were relatively poor in the 1950s have remained relatively poor. Countries that were not consolidated or full democracies have, with rare exceptions, not become fully consolidated democracies.

Above all rulers want to stay in power. Losing office in many countries can mean poverty, exile, or even death. In fully democratic societies rulers can stay in power only if they win free and fair elections. In most of the world rulers stay in power because they are able to secure the loyalty of those who control the instruments of violence.

Foreign assistance has become, since the second world war, a conventional practice in the international system. Before the second world war there was no such thing as foreign aid. In absolute terms the United States is the largest official aid donor. As a percentage of GDP, the United States has always been near the bottom of the list of aid donors. According to OECD figures, American foreign assistance was 0.17 of its GDP in 2015. The largest aid donors in percentage terms were Sweden at 1.4 percent of GDP and Norway at 1.04 percent. The most generous large country donor was Britain, which provided 0.7 percent of its GDP as overseas development assistance in 2015. If the United States were to abandon foreign assistance entirely, it would put our country outside norms that have been widely accepted in the wealthy democratic world.

Although foreign assistance has been a widely accepted practice for the seventy years its record of accomplishments is thin. In the 1950s, the widely held assumption in the United States and elsewhere was that if countries received foreign aid they would be able to close the investment gap; if they were able to invest more, they would grow faster; if they had higher levels of growth, they would have a larger middle class and a larger middle class would be the foundation for a democratic political regime. This very optimistic and straightforward story has, alas, not come to pass. The only country that has substantially changed its place in the international ordering of wealth and democracy, that has gone from being poor and autocratic to rich and democratic is South Korea. The per capita income of South Korea at the end of the Korean War was at the same level as the colonies of West Africa; today South Korea is a member of the OECD with a per capita income of $25,000. Empirically, it has been very difficult to establish any clear relationship between the amount of foreign assistance that a country has received and its pattern of economic growth.

The classic assumption of foreign assistance is that leaders want to do the right thing; they want to improve the living conditions of their own people. This assumption is wrong. Political leaders want to stay in power. In democracies they must respond to the demands of most of their people. In non-democracies, they only need to satisfy the demands of a small part of their population: those people, most of whom have guns, that they need to keep them in power.

The United States does confront a genuine dilemma. For reasons associated with our own security – especially related to transnational terrorism and pandemic disease – we need to improve governance in badly governed states, but at the same time our traditional aid programs, which assume that political leaders in non-democratic states want to do the right thing for their own people, have not been successful.

We need to re-think the objectives of foreign assistance designed to promote growth and political change and to distinguish foreign assistance from humanitarian programs that save lives, even if they do not change polities. Our fundamental objective should be American national security. We need to identify programs that are consistent with our own interests and with the interests of political elites in target states. We have to find the sweet spot where our interest overlap.

The fundamental objective of our foreign assistance program should be SHE:

- Security,

- Health,

- Economic growth.

These three goals are consistent with our interests and with the interests of elites in target states, even autocratic elites.

All leaders want effective security. They want to be able to effectively control their own territory. If they can effectively control their own territory they can address transnational terrorist threats. If leaders support transnational terrorists, as the Taliban regime did in Afghanistan, we face starker choice. We have no choice but to displace such a regime. The use of American military power is very costly in terms of treasure and more importantly in terms of lives. The more effective our diplomacy and development is, the less we will have to rely on our very impressive but very expensive military. Security assistance, especially strengthening the policing capabilities of poorly governed states, is one primary objective that we should aim for.

Better health is the big success story of the postwar period. In many countries life expectancy has increased by 30 years. Even in some very poor countries like Bangladesh, which now has a per capita income of $1200, life expectancy increased from 46 years in 1960 to 72 years in 2014. All leaders can reap some benefits from the better provision of health. Better health does not threaten political leaders. Various international programs, such as the elimination of smallpox which was led by the World Health Organization, and national programs such as PEPFAR, which was initiated by the George W. Bush administration have saved lives and highlighted American generosity. Better monitoring, which might be achieved even in states with poor governance, can help to prevent naturally occurring pandemic outbreaks that could spread around the world. Ebola was quickly halted in Nigeria because of a polio-monitoring program that had been put in place by the Gates Foundation.

All leaders will accept some economic growth if that growth does not threaten their own position. Poorer states will not easily become dynamic market economies where economic changes can threaten the political leadership, but political leaders will want to provide more jobs for their populations. No foreign assistance program can guarantee sustained positive growth over the long term, but we can provide some growth, and higher levels of per capita income. More jobs will make countries more stable and make it more likely that they will ultimately transition to democratic regimes. The most effective way to encourage economic growth is to provide incentives for leaders in poorly governed states to introduce growth-enhancing policies. One example of such an effort is the Millennium Challenge Account, a program that I worked on while I was at the National Security Council in 2002. The MCA has received funding of about $1 billion a year. The MCA is selective. It only provides funding to countries that have passed third party criteria related to governing justly, investing in people, and enhancing economic freedom. Countries on the threshold of receiving passing grades have altered their policies to improve conditions for economic growth.

In addition to SHE (security, health, economic growth) there are two other objectives that American foreign assistance broadly understood can address. First, we can limit the impact of humanitarian crises. There are several countries that are threatened with famine. Civil strife especially in the Middle East and Africa has led to many internally displaced people and to international refugees. USAID has expertise in addressing these issues. The United States has been a rich and generous country. Abandoning humanitarian assistance would be a violation of American values and would threaten our security by widening the area of ungoverned spaces.

Second, we might be able in some special circumstances to stop conflicts before the spread. I have been a member of the Board of Directors of the United States Institute of Peace since 2008. The Institute was established by President Reagan. It works in very dangerous places in the world such as Afghanistan and Iraq. It can hire foreign nationals, who are familiar with the local environment, more easily than other agencies of the American government. It has helped to mitigate conflict in places like Tikrit in Iraq after Saddam’s home city was re-conquered by government forces. The entire budget of USIP is about $35 million a year, about the cost of keeping one U.S. military platoon in Afghanistan for a year.

To enhance our own security we should support regimes in other countries that can effectively control and police their own territory, provide some level of services especially in the area of health, and accept some improvement in economic opportunities. Foreign assistance programs will not work unless the interests of American policy makers and those in target states overlap. This will only happen if American policies do not threaten foreign leaders. We should not try to transform poorer countries but we should not ignore them either because of the dangers of naturally occurring pandemic diseases, manmade biologicals, and transnational terrorism.

Foreign assistance including support for the military and police, better provision of health, and some economic programs can further the security interests of the United States and the interests of political leaders in poorer countries. Our foreign assistance should aim for these more modest objectives -- better security, improved health, some economic growth – which are in both our interest and those of leaders as well as populations in poorer countries.

To guarantee our security we need a strong military, but it must be a military that we do not have to use very often. Diplomacy and development are complements to defense, not rivals. Effective American leadership requires the three D’s: defense, diplomacy, and development. Without American leadership there will be vacuums and these vacuums will be filled by countries that do not share our norms and values. Gutting development and diplomacy would make us weaker not stronger. The United States needs all three instruments of national power, not just one.