Tripoli’s Banners, Graffiti Signal Potential Wrangles Ahead in Libya

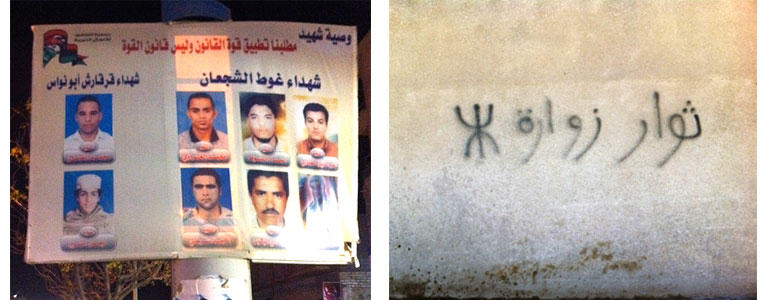

Pictured left: A poster in the Gergarish neighborhood of Tripoli shows some of the fighters lost in Libya’s revolution with the words, "Our demands are to implement the strength of law and NOT the law of strength." right: Graffiti scrawled in the Hay Alandalus area of Tripoli displays the sign of the Amazighi indigenous people of Libya, followed by the words "Fighters of Zwara" a city in the Nafusa mountains.

Alongside the red, black and green flag of Libya’s new democracy, Tripoli’s streets are decorated with another symbol of the struggle for liberty: digitized photographs of the fallen in every neighborhood, proudly displayed as signs of the community’s sacrifice for the new nation. Graffiti washes over the city with messages declaring, “The fighters of Tripoli” or “The Eagles of Zintan” and so on.

This urban art should not be taken at face value; these symbols of pride, ownership and personal glory are nuanced messages of potential conflict in Libya if leaders don’t take care to ease the strains that underlie the artistic missives.

The photos of the martyrs are stark reminders of what was lost for the national cause and represent a festering anger aimed at the government, not only as a result of the conflict’s damage but also over the lingering ills of the now-defunct system of autocratic rule.

Leaders of the transition can’t be expected to repair the damage and cure the ills overnight, and the country isn’t likely to revert to revolutionary intensity. But officials could alleviate some of the stresses and tension of post-conflict Libyan life with steps such as improving medical services and establishing public-outreach programs to highlight for citizens the progress that has already been made, as a means of encouragement that improvements are on the way.

In turn, the Libyan people, newly independent from the clutches of government, have to be careful not to take undue advantage of assistance programs intended primarily for victims of the conflict such as those who were injured or disabled, targets of rape and sufferers of post-traumatic stress.

The graffiti found throughout the capital reflects the desire of local communities to express their pride and tout their contributions to the national cause. Rather than ignoring the signals, the government could weave such sentiments into a new, unified Libyan identity.

Creating an updated Libyan national identity remains fundamental to the survival, stability and prosperity of the new state. Though Libya is certainly not fragmented like other Arab nations in transition, Libya’s geopolitical landscape tells the story of a nation struggling to recover from four decades of “divide and conquer.”

The wealth of Sirte, for example, contrasts with the barren landscape of Benghazi; the passivity of the populace in Tawergha before and during the revolution highlights the defiance of their neighbors in Misrata; the perceived abundance of Tripoli belies the reality of a stark, decaying urban landscape, even in the capital’s historically affluent neighborhoods.

Media and social networking sites could do much to bring communities together by giving voice to the diverse Libyan population. National holidays like the forthcoming February 17th anniversary of the revolution provide an opportunity to educate, inspire, and engage Libyans, rather than becoming a platform for mediocre speeches with vague promises and uninspiring delivery.

Among the most daunting indicators of potential conflict are the spray-painted declarations of ownership of properties unjustly seized during the Qaddafi era: “Al-Baytu li sakinihee” loosely translates to “the house is for he who dwells within,” a government policy that encouraged and protected those who essentially stole property from others.

Qaddafi used this policy of usurping community land and rewarding neighboring towns with the spoils as a way of sowing distrust and the seeds of fragmentation in an effort to stifle any potential unified opposition movement. Such property claims raise red flags that may lead to larger clashes, or even conflict, down the road, unless officials adopt a proactive approach to resolving the disputes.

History shows Libyans are patient people; but when their patience wears thin, they rise fearlessly. Thus, it is essential that the current transitional government, civil society and the international community read the writing on the walls and collaborate actively to prevent a descent into renewed conflict that the messages portend.

So have you seen cases where urban art has signaled societal tensions, or where it’s been used constructively to forge social unity? Let us know by posting your comment.

Rania Swadek is a program specialist for USIP in Tripoli.