Constitutional Reform in Iraq: Improving Prospects, Political Decisions Needed

U.S. and Iraqi politicians and analysts consistently agree on one central point concerning Iraq: serious political reconciliation amongst Iraqi groups is needed to reduce the violence and create a viable government.

U.S. and Iraqi politicians and analysts consistently agree on one central point concerning Iraq: serious political reconciliation amongst Iraqi groups is needed to reduce the violence and create a viable government. Centrifugal forces fueled by armed conflict, competition for power and resources, and the intervention of foreign powers and neighbors has stalemated the political process in Baghdad for months.

Several key benchmarks of political progress are tied to the ongoing constitutional reform process. In accordance with Article 142 of the constitution adopted by referendum in 2005, the Council of Representatives (COR) established a Constitutional Review Committee (CRC) in late 2006, responsible for proposing amendments to that document. The principal reason for this constitutional review so quickly after adoption of the new constitution was to provide Sunni negotiators an opportunity to engage in the process of constitutional design from which they felt they were excluded in the prior round—the 2005 constitution is mainly a Shia-Kurdish compact. The CRC has 29 members representing the political blocs in the parliament, 13 of whom served on the committee that drafted the 2005 constitution.

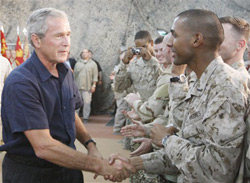

Right: President Bush greets troops in Anbar province, Iraq, Monday, Sept. 3, 2007. The president made an unannounced visit to Iraq to meet with Gen. David Petraeus, commanding general of the multinational forces in Iraq, U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Ryan Crocker, Iraqi leaders, and U.S. troops. (Photo Courtesy: AP)

Right: President Bush greets troops in Anbar province, Iraq, Monday, Sept. 3, 2007. The president made an unannounced visit to Iraq to meet with Gen. David Petraeus, commanding general of the multinational forces in Iraq, U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Ryan Crocker, Iraqi leaders, and U.S. troops. (Photo Courtesy: AP)

On May 22, the CRC submitted its report to the Council of Representatives (COR), proposing dozens of amendments. Given the sectarian tensions in the background of this process, it is notable that Sunni members on the CRC have indicated that they achieved the majority of amendments they were seeking and are inclined to urge their party leaderships to support the proposed package of constitutional revisions.

What is needed now is a top-level decision to move ahead with amendments in as many areas as possible. Without that, improved prospects may never be realized and the constitutional revision process will—like so many other things in Iraq—fall victim to stalemate and uncertainty.

Significant proposed amendments are in five areas:

The distribution of oil revenues: Changes to articles 111 and 112 explicitly guarantee the even distribution of hydrocarbon industry revenues based on population size, regardless of the source. Language referring to a distinction between existing and future (as yet untapped) resources was also removed. Although numerous technical details remain to be negotiated in the oil/gas laws being drafted, these two changes remove the primary conceptual hurdles to agreement by all sides.

The Federation Council: Article 65 of the 2005 constitution called for the creation (by law) of an upper house of the parliament to represent the interests of the federal entities. There has been widespread agreement that the provisions defining the powers and composition of this important body—which would serve as the lone forum for coordination and debate among the regions and governorates—should be incorporated directly into the constitution. The CRC has proposed a Federation Council made up of an equal number of representatives per governorate, regardless of population size or prior incorporation into a region. The representatives would be directly elected by the population of each governorate, with an unspecified number of seats reserved for minority groups. The legislative jurisdiction of the Federation Council would extend only to those areas directly within the competence of the federal regions, as defined by articles 110-115 of the 2005 constitution.

Taxation and other federal powers: One major concern about the 2005 constitutional arrangements was the lack of key federal powers over national issues, as well as the inability of the central government to raise revenues through taxation. Proposed amendments have added a litany of federal powers, including taxation and policy oversight of water, environmental protection, nuclear power, and customs.

Judiciary: A number of amendments were made to increase the independence of the federal judiciary, and to strengthen the power of the Federal Constitutional Court (a renaming of the current Federal Supreme Court) to address conflicts among various federal entities, including the central government, regional government, governorate governments and local governments, as well as between the Council of Representatives and the Federation Council. The Federal Constitutional Court will also have enhanced powers to ensure civil and human rights standards by overseeing the constitutionality of regional constitutions and laws.

Independent commissions: Proposed amendments would strengthen the writ of several independent commissions provided for in the 2005 constitution, including an Independent Human Rights Commission, an Independent Electoral High Commission a Commission on Public Integrity, and a Board of Supreme Audit. In addition, an Independent High Commission for Promotion of the Constitution is envisioned, which would serve to safeguard citizens' rights and would have the power of petition to the Federal Supreme Court on issues of constitutional interpretation. These commissions are intended to increase governmental accountability and combat corruption and nepotism.

Overall, these amendments would have the effect of giving greater coherence to the central government in Baghdad, while also guaranteeing federal autonomy. The proposed amendments are far from perfect, and leave several problematic ambiguities in the constitution. The most significant remaining gap may be the lack of a clear definition of the process of regionalization and administrative boundary drawing, as well as the status of governorates versus regions within the constitutional framework.

It is now up to the COR to debate these amendments. As this deliberation begins, a five-member subcommittee of the CRC has been tasked with developing proposals regarding a few remaining contentious issues by September:

Kirkuk: Kirkuk is an oil-rich, ethnically diverse province in the northern part of Iraq. Tensions over forced migration and gerrymandering under Saddam's rule, combined with Kurdish ambitions to incorporate it into Kurdistan, have made Kirkuk a flashpoint of ethnic and sectarian conflict. The constitution currently requires that the status of Kirkuk be resolved by referendum by the end of 2007, and efforts are underway on all sides to create demographic "facts on the ground" in advance of the referendum.

The status of Kirkuk is the most serious of the remaining obstacles to agreement on constitutional amendments, because the Kurds have now apparently made agreement on other amendment issues contingent on favorable resolution of the Kirkuk issue. Kurdish negotiators have proposed a binding political pact between the leadership of the Shia, Sunni and Kurdish blocs to return the administrative boundaries of Kirkuk to the 1970 map, thereby adding four Kurdish-majority surrounding districts to Kirkuk and ensuring Kurdish success in any future referendum. Tawafuq, a leading Sunni party, is opposed. The Shia bloc is also not in favor, since it would undermine Sunni acceptance of the CRC amendments in an exercise intended to garner their support for the political process. Kurdish representatives have not accepted counter-proposals, including extension of the referendum deadline for 3-5 years, or organization of Kirkuk and some surrounding villages into a region that could not be incorporated into any other region. Recently, it has been suggested that Kurdish representatives might agree to a district-by-district referendum, which would allow substantial portions of Kirkuk governorate (possibly including Kirkuk city) to choose not to be incorporated into Kurdistan.

Early in the process to identify a solution for the Kirkuk stalemate, key members of the CRC leadership felt that greater American and UN intervention would have been useful. As developments in the political arena changed over the summer months, the focus for a solution has become more and more dependent on resolution of the overall political stalemate facing the Iraqi government following the walkout of Tawafuq and Al-Iraqia bloc ministers. Pending efforts to bring together key blocs in a leadership council are viewed as a necessary condition to solving this and other outstanding areas of disagreement.

Presidential Authority: The 2005 constitution sets forth a parliamentary form of government in which power is now distributed between a relatively strong prime minister and a weaker president. Some Kurds and Sunnis on the CRC would like presidential powers increased. While this appears possible to some degree, the UIA (majority Shia bloc) have indicated that they will agree to major changes only if the President is chosen through direct elections (which would then be shaped by Shia numerical superiority).

De-Ba'athification: While not a constitutional issue, review of de-Ba'athification remains a critical element on the political reconciliation agenda. As per the request of the COR leadership, the CRC subcommittee is attempting to develop consensus principles on de-Ba'athification reform. Among the ideas being considered is reforming the deficiencies in prior laws and incorporating a vetting process that would consider individual cases rather than the current system of exclusion based on broad categories of party membership—thus hypothetically allowing greater political and civil service participation to former regime officials who were not engaged in crimes against the Iraqi people.

Under the 2005 constitution, the package of amendments must be voted on in a national referendum within two months of approval by the COR. The UN, however, believes that a referendum would not be logistically possible before the end of 2007. If this process is to contribute to national reconciliation in Iraq, it is essential that sufficient resources, time and attention are devoted to public education, in order that an informed Iraqi public can participate in the ensuing debate and referendum. The failure to allow for public debate and education in the 2005 constitutional process is one of the reasons amendments are needed now—and it would be a serious mistake to compound the original error by rushing the current process.

This USIPeace Briefing was written by Neil J. Kritz, associate vice president of the Rule of Law program; Sermid al-Sarraf, executive director of the International Institute for the Rule of Law; and J Alexander Thier, senior rule of law advisor in the Rule of Law program at the U.S. Institute of Peace. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Institute, which does not advocate specific policies.

The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan institution established and funded by Congress. Its goals are to help prevent and resolve violent international conflicts, promote post-conflict stability and development, and increase conflict management capacity, tools, and intellectual capital worldwide. The Institute does this by empowering others with knowledge, skills, and resources, as well as by directly engaging in peacebuilding efforts around the globe.