Building Regional Border Security Cooperation: Lessons from the Maghreb

The Maghreb countries of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia face threats to their borders from transnational illicit networks, such as terrorist groups and criminal organizations. To address these threats, USIP convened operational border officials from the three countries through a series of workshops in spring 2016. This brief highlights the key lessons that emerged from this work: addressing border security requires understanding the underlying drivers of insecurity; border security requires states to maintain legitimacy and support from the broader population; and ground the strategy to address insecurity through operational realities.

Summary

- The three Maghreb countries—Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia—share a threat from terrorist and transnational organized criminal networks, such as Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb, the so-called Islamic State (also known as Daesh, ISIS, and ISIL), and arms, drugs, and human smugglers, that are active throughout the region and beyond and have exploited the vulnerabilities of national borders.

- A series of workshops with border operations officials in the Maghreb provided valuable lessons for creating a regional border security cooperation plan—a critical component of global peacebuilding efforts.

- A plan to establish sustainable regional border cooperation must address underlying drivers of insecurity, be rooted in the rule of law, and engage border communities as partners.

- Effective border cooperation requires governments to address the needs and grievances of border communities, which are often politically, socially, and economically marginalized, and to involve multisector government and nongovernment stakeholders.

- Engaging operational officials in developing a plan for regional border security cooperation grounds strategic thinking in the operational realities of the affected countries. It reveals the margins within which regional cooperation opportunities may exist as well as how these opportunities can be leveraged to promote political support for regional cooperation.

- A strategic plan that is driven by operational needs and realities results in a comprehensive, overarching vision and recommendations for action that are contextually relevant, technically sound, and politically persuasive.

Introduction

Transnational illicit networks, such as the Islamic State, al-Qaeda and their affiliates, and criminal organizations that move drugs, weapons, and people, threaten border security in all regions of the world. The nature and global reach of these threats challenge traditional perspectives of borders as territorial lines to be defended and have led to a realization that border security involves multiple layers requiring varied and coordinated responses. No country can effectively address border security management unilaterally; simultaneous multilateral, bilateral, and national cooperation is required to respond to and mitigate these threats.

This Peace Brief outlines lessons learned by the United States Institute of Peace during a series of workshops held in the spring of 2016 with border officials from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The workshops applied an operations-driven approach to the development of a joint strategic vision for regional border security cooperation that is grounded in human security and rule of law principles. The outcomes from the workshops provide important lessons for developing a plan for border security cooperation in other regions, which in turn can provide critical support to peacebuilding efforts where borders are used opportunistically by terrorists, militants, and criminals to evade law enforcement and create tension between neighboring states. Effective border security that blocks illicit networks while allowing the legitimate flow of peoples and goods can contribute to building strong ties between states and empower border communities.

Regional Border Challenges: The Maghreb Context

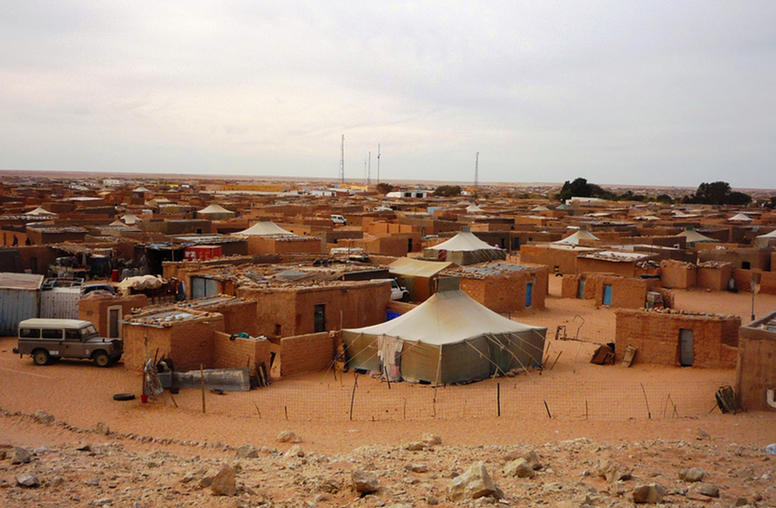

The countries of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in the Maghreb region face pressure from terrorist and other organized criminal networks that have been empowered to expand their operations since the so-called Arab Uprising. These illicit networks have seized the opportunity to exploit regional security vulnerabilities that increased as states turned their focus away from borders to address internal unrest. The collapse of the Libyan state has contributed to an increase in the flow of weapons throughout the region. Long-existing smuggling networks operating along established routes, and promoting illicit economies in marginalized border areas where low-level corruption is prevalent, are susceptible to being co-opted by new and heavily-armed opportunistic groups.

Limited institutionalized regional cooperation and imbalances in the border security capacity of neighboring states have further contributed to the vulnerability of borders. Existing border security cooperation tends to be carried out bilaterally and often in an ad hoc manner. Technical organizations, such as INTERPOL and the World Customs Organization, provide a degree of coordination through shared databases, trainings, and practices. However, there remains a need for more targeted and regional-specific mechanisms designed to address the distinct challenges, dynamics, and capacities of the Maghreb countries.

A Foundation for Establishing Border Security Cooperation

A core message that emerged from the workshops was that border security is not merely about protecting a territorial line; it requires understanding and addressing the underlying drivers of insecurity and the diverse range of actors contributing to and affected by these drivers. Officials attending the Maghreb workshops identified the economic and political isolation of their border communities and the strained relations between those communities and state officials, particularly in the justice and security sectors, as key drivers of border insecurity in their region. One Tunisian official explained their dilemma: “We have to shoot at some of them [traffickers], which has serious repercussions. But sometimes traffickers are facing social problems. How can you shoot at them based on that? How can you shoot a fellow Tunisian?”

Officials recognized that operational success in securing and managing borders can be achieved only in an environment in which state institutions and the legal system they uphold have legitimacy for border communities. Legitimacy, both perceived and actual, requires that the state upholds the rule of law and protects the basic rights and freedoms of all people and takes action to respond to the specific needs and underlying grievances of border communities, including prioritizing the economic development of those communities. This component must involve a range of stakeholders beyond the core border security agencies, including trade, economic development, health, and education ministries; justice institutions; other law enforcement agencies; local communities; and local government authorities.

Border security can be established and sustained only with the support of border populations. Concerted efforts need to be made to rebuild trust and establish partnerships between border security agencies and communities on both sides of the border. As one Tunisian official stated, “In these communities, there is no notion of the term ‘borders.’ They’re dealing with each other on a daily basis.” Establishing partnerships through dialogue, consultation, and clear action, including the coordinated and complementary community engagement by security officers on both sides of the border, will help to enhance public trust and confidence in security institutions generally, will contribute to the increased operational effectiveness of those institutions in combating specific border security threats, and will ultimately lead to more stable border areas.

Applying an Operations Driven Perspective to Regional Border Security Planning

The workshops brought together operational-level officials, including border guards, customs, and national security officers, around a common point of technical interest: how to better secure their borders. They discussed common challenges and shared firsthand knowledge and expertise, identifying margins of opportunity for cooperation beyond the political challenges. They identified existing tools and tested approaches to border security cooperation that could potentially be leveraged for greater regional cooperation. An Algerian official noted, “Working in the field, we all know what needs to be done. When we talk with each other, we’ve all seen that we have no problem working with our regional colleagues.”

The workshops revealed that an operational-focused approach to strategic planning can be valuable in both identifying and promoting specific opportunities for successful regional cooperation. Indeed, this approach has resulted in the establishment of at least two cross-border organizations, INTERPOL and the Southeast European Law Enforcement Center. Both organizations emerged from law enforcement officials identifying a need to cooperate across borders on specific criminal issues. Each technical success resulted in an incremental growth in regional and even global cooperation.

Involving operational-level officials from across border security-related agencies and ministries in high-level strategic planning processes can also ensure strategic thinking on border security and regional cooperation is anchored in operational reality. By harnessing existing operational expertise, strategic plans for border security are more likely to address actual border security needs and be feasible in terms of implementation and achievements.

Eventually, any regional plan needs to address the politics of cross-border cooperation. According to workshop officials, the nature of today’s border threats and the responses required to effectively address them makes regional cooperation between the three Maghreb countries critical. Yet attempts to establish greater cooperation have stalled at the political level. Weak political will and a strong institutional hierarchy were hurdles cited by operational officials, who expressed frustration at their limited political influence. A Tunisian official noted, “[W]e are all concerned about shared threats. We will report this to our superiors [after this workshop] and they will report it to theirs. But we’re technicians in the field. We’re not politicians.”

However, as the strategic visioning process evolved, officials began to explore how they might make their cases to policymakers. They ultimately agreed that they should facilitate the understanding of policymakers as to the nature of, and appropriate responses to, threats of terrorism and transnational organized crime to promote awareness of the necessity of regional cooperation. A Moroccan official suggested that initiating low-risk forms of cooperation and publicizing the resulting operational successes could encourage broader regional cooperation. He cited the example of the Moroccan Royal Gendarmerie’s cooperation with Spanish authorities, which was so successful that “our colleagues in other police units also introduced projects. Now we have Spanish police officials who work in our international airports, and vice versa.”

A New Approach to Strategy Development

The overall goal of the workshops was to develop a Joint Strategic Vision for regional border security cooperation. The process was seen to be as critical as the final product for ensuring the strategy was contextually relevant, operationally sound, and supported by those who will ultimately be called upon to implement it (i.e., officials working in border areas). As such, an experimental approach to the strategic visioning process was tested that specifically drew upon the technical expertise of operational officials to produce a coherent and tangible strategy that was grounded in the operational reality of each of the involved Maghreb countries.

A strategic visioning process normally begins with defining the vision statement and then moves downward to identifying specific actions needed to achieve the vision. Those involved in the process often lack critical information about on-the-ground realities, and the resulting strategies can be unrealistic, abstract, and impossible to implement. In contrast, the approach tested during the workshops began with the concrete operational and strategic recommendations agreed upon by officials during the first two workshops. These recommendations were combined, debated, and framed into categories that formed a set of clear strategic objectives, from which the officials were able to distill a clear mission and vision statement. This bottom-up approach to strategic visioning produced a strategy that was realistic and politically persuasive due to its sound technical foundation and ability to be operationalized. Their technical expertise and practical experience led the officials to the inescapable conclusion articulated in their vision statement: “The three Maghreb countries—Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia—have a shared interest in addressing the common challenges and threats posed by terrorism and all forms of transborder crime. In this regard, regional cooperation is unavoidable.”

Conclusion

Placing operational officials at the center of the process of developing a strategic vision for regional border security cooperation is an effective approach for achieving a strategy that is contextually relevant, operationally feasible, and politically persuasive. These workshops also revealed the critical importance of addressing border security through a comprehensive and people-centered framework that addresses the root causes of border insecurity and therefore must involve a multiplicity of government and nongovernment stakeholders. It is clear to operations officials that border security cannot be achieved by their agencies or nations alone. Faced with the urgent need to address common threats to security in the region, operational officials have a critical role to play in promoting greater regional cooperation. A Moroccan official best summed up this role: “During these workshops, I’ve seen that we identified the same challenges and share the same recommendations. This is comforting because it shows that there is good will to enforce and strengthen cooperation, hand in hand, to combat these phenomenon eating our region. Expressing the same challenges and abilities is a positive point that shows we are willing, together, to achieve the best results in securing our borders.”

About this Brief

This brief synthesizes lessons learned from the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Regional Border Security Cooperation in the Maghreb project. Through workshops with operational border officials from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in the spring of 2016, participants highlighted the need to develop effective and inclusive strategies to secure borders that would both build strong ties between states and empower border communities. James Cohen and Joyce Kasee Mills led the project while at USIP. Leanne McKay was a consultant for the workshops.