How can protesters use lessons from the 2015 demonstrations to better demand accountability and transparency?

Guatemalans have once again risen up by the thousands to demand major changes in how their country is governed. Their demands are intended to usher in reforms that will improve quality of life for citizens reeling from the impacts of two deadly hurricanes, as well as health and economic crises that have only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The demonstrations are reminiscent of the 2015 protests that prompted the resignations of top officials, including the country’s president. However, that movement fell short of broader, structural change. This time around, protesters can draw on lessons learned from the past to achieve long-term reform and target Guatemala’s persistent systems of corruption.

The recent mass mobilizations were sparked by a nearly $13 billion national budget, the largest in the country’s history, that was passed by Congress but cut funding for health care, education, and human rights. The late-night move by lawmakers was especially egregious given that the legislation cut $25 million for combatting malnutrition in a country struggling with food insecurity—all while increasing the amount lawmakers themselves receive for meal stipends and other expenses.

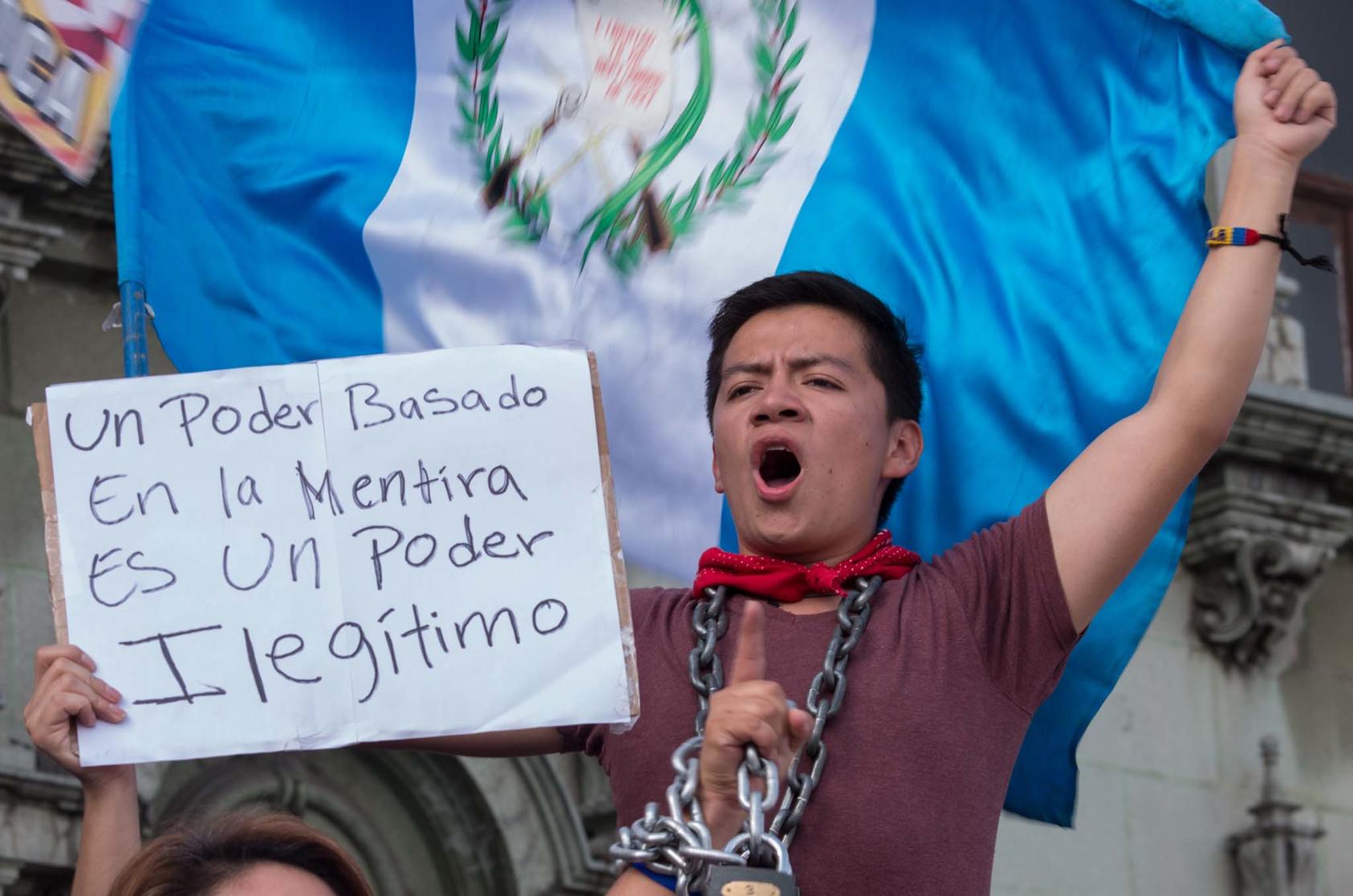

The protests, starting November 21, 2020, garnered widespread attention after the Congress building was set ablaze during a demonstration in the capital, Guatemala City. Yet, the streets in at least 10 departments countrywide filled with people waving the blue-and-white national flag, chanting, playing music, and holding signs denouncing corruption. The demands from the streets were accompanied by calls to veto the bill from the private sector, the Catholic Church, the state-funded University of San Carlos, and indigenous groups. In the face of the organized mass action, lawmakers were ultimately forced to shelve the budget, signaling a victory for protesters.

A Familiar Problem

The current situation has left many drawing comparisons to Guatemala’s mass mobilizations in 2015 that forced President Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti to step down. Both former leaders were jailed on corruption charges after hundreds of thousands of people engaged in a variety of nonviolent action tactics rallying around the RenunicaYa (Resign Now) slogan.

At the time, the pressure from large swaths of civil society and the RenunciaYa movement was accompanied by efforts from an international anti-corruption body operating inside the country. The International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), backed by the United Nations, was a unique institution in that it worked with state prosecutors on the investigation and prosecution of organized criminal networks with ties to political actors.

However, after bringing a number of high-profile cases, the CICIG came under attack and was ultimately expelled in September 2019 by President Jimmy Morales after he became a target of a CICIG investigation. CICIG’s collapse allowed the corrupt networks involving political and business elites to persist—as well as opened the door to backlash against those working to root out corruption in state institutions. With a through-line from 2015 to now, it’s clear that lawmakers’ latest budget attempt was seen as the last straw for many Guatemalans.

Takeaways from the Recent Past

As the country remains plagued by corruption and other major issues, such as high poverty and unemployment, lessons drawn from the 2015 movement can help those organizing and mobilizing for change in Guatemala now.

In 2015, youth and members of the urban middle class, who comprised most of the movement, were unable to strategically connect with Guatemala’s longstanding indigenous movements that have been, and continue to be, at the forefront of work to protect human rights and advance justice. Activism by indigenous groups against discrimination, exclusion, and violence has laid the groundwork for pursuing the types of broader structural changes required to eradicate corruption and reduce inequity. And USIP-supported research found that the inability of the 2015 protests to effectively draw on this foundation and strategically partner with indigenous movements hampered the push for lasting changes.

Studies on nonviolent action suggest movements are more effective at achieving their goals when they elicit diverse participation across a wide range of society. This current wave of protests can avoid the shortfalls of 2015 by focusing on movement-building work to both strengthen existing coalitions and form new ones across social, political, and economic lines.

Additionally, much like 2015, calls for legislative and presidential resignations have been a part of the 2020 protests. But even after the 2015 movement emerged and forced the departures of the country’s top leadership, it was apparent that the entrenched systems of corruption were still very much intact.

This time around, protesters can also emphasize more fundamental demands, such as addressing issues of justice and human rights pushed by longstanding indigenous movements. This can help ensure that mobilizations to advance transparency, accountability, and democratic governance encompass demands for institutional reforms rather than just focusing on getting people in power to resign. Emphasis on the latter approach can be easily taken advantage of by political elites who simply want to demobilize citizen-led demonstrations rather than implement necessary changes for more structural reforms.

Álvaro Montenegro, a member of JusticiaYa, a social movement formed by members of RenunciaYa, also identified the importance of organizing to strengthen movements—particularly between protests—as a key takeaway from the 2015 mobilizations. “Elites should not be allowed to take advantage of crises to re-functionalize the corrupt system,” he said. “Mobilizations cannot last forever, but strengthening social networks helps to reactivate them in tense moments, which is very necessary to politicize social actors in order to be aware of the depth of the country's problems.”

Differences Between Then and Now

There are some stark differences between the 2015 movement and the current moment—the presence of COVID-19 being a major one. The thousands of (mainly mask-wearing) Guatemalans who took to the streets starting at the end of November showed people’s willingness to engage in great risk to push back against poor governance and fight injustice. While the pandemic has posed significant challenges for activists around the world, Guatemalans have adapted their tactics, including a ramping up of digital activism, in a way that aligns with recent research on how social movements can remain effective amid COVID-19.

Protesters in Guatemala today are also facing the absence of CICIG, which had wide support among the population in the years leading up to its departure. As CICIG exposed the embedded nature of corruption in Guatemala and brought cases against politicians, judges, and other government officials, Guatemalans poured out into the streets for mass protests calling for the accused to be held accountable, giving CICIG and attorney general’s office more political strength to continue their investigations. Both the institutional and extra-institutional anti-corruption work had helped to advance a culture shift toward ending impunity by generating momentum for one another. But now with CICIG gone and the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI) left under-resourced to carry out high-profile investigations, citizens have less support in the already challenging anti-corruption fight.

This round of protests has also prompted violent repression from the police not seen in recent years. Various human rights groups, including Amnesty International and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, denounced the excessive use of force by police. The crackdown not only prompted outcry from activists and civic groups on the frontlines—opposition parties in Congress called for the resignations of the director of the national police and the interior minister.

An Attempt at Dialogue: Where to Go from Here

Despite the many challenges, protesters have continued taking to the streets and deploying other nonviolent action tactics, such as highway blockades staged by indigenous groups and rallies, to demand presidential, legislative, and judicial resignations and an end to corruption.

Faced with mass protests calling for his resignation less than a year into his tenure, President Giammattei announced plans for a dialogue, requesting help from the Organization of American States (OAS). However, many civil society organizations did not trust the government-hosted process, and several groups pulled out or declined invitations.

In a sign of hope, the sustained pressure appears to have made somewhat of an impact. President Giammattei and Vice President Guillermo Castillo—who had initially opposed the budget and suggested both he and the president resign—recently agreed to make some concessions. The two leaders united to announce the dismantling of the Centro de Gobierno, a controversial government coordinating body, as well as an evaluation of the fitness of all ministers and vice ministers to remain in their positions and a review of the 2021 national budget, which remains under discussion. While their announcement signaled a clear win for people power, citizens are still demanding broader structural changes to address longstanding issues of exclusion, discrimination, inequality, and violence. Their calls should be heeded in order to advance justice and peace in the country.

Carlos Mendoza is an academic coordinator for Dialogos, a Guatemala City-based think tank that seeks to promote the dissemination and advancement of empirical and social science research.