On the Issues with Fiona Mangan and Igor Acko

Nine months after the Central African Republic (CAR) held free, peaceful and democratic elections for president and parliament, the country continues to struggle for stability and progress. Half of the country remains in need of humanitarian aid, and an increase in violent incidents since September threatens to destabilize any progress made to date. At the end of November, clashes between factions of the ex-Séléka, a formerly united alliance of primarily Muslim armed groups, left 85 dead, 76 injured and 11,000 newly displaced. The targeting of a specific ethnic group in the fighting, the Muslim Fulani/Peuhl community, raises concerns of a descent into ethnic cleansing such as occurred in early 2014. U.S. Institute of Peace experts Fiona Mangan and Igor Acko discuss the current status of armed groups, the barriers to disarmament, and continued international engagement in CAR.

Mangan recently returned from nine months in CAR, where she served as USIP’s country representative. Acko, a sociologist and analyst, coordinates the institute’s programming and research in CAR in an effort to curb the violence that has long plagued the country.

It has been four years since the then-united Séléka began an insurgency that seized power for a time, provoking prolonged retaliatory fighting with primarily Christian and animist self-defense groups known since then as the Anti-Balaka. Despite disarmament talks with the government, armed factions control much of the countryside, and deadly sectarian tensions persist. The Ugandan and French troops that had provided much-needed security and stability are pulling out.

Can you provide us an overview of the situation today in the Central African Republic?

Mangan: The Central African Republic is trying to rebuild after having experienced repeated waves of violent conflict over the past 20 years. President Faustin Archange Touadéra took office in March 2016 following peaceful elections, and he set as his top priority getting the country’s array of armed groups to drop their weapons. He has made some effort to engage armed group leaders in negotiating a process for disarming, demobilizing and reintegrating their fighters, but has been unwilling to engage on key demands of the armed groups. As a result, certain crucial factions refuse to go along with the proposal and the reality is that they continue to control large parts of the country.

In addition, ongoing violence and insecurity prevent the return of the nearly 1 million people displaced by the conflict either internally in CAR or as refugees in neighboring countries. Under these conditions, it’s very hard to work toward state-building and national reconciliation.

What makes disarmament so challenging in CAR?

Acko: DDR [disarmament, demobilization and reintegration] is a challenging process in any post-conflict context, but CAR's history makes it even more so. There were two previous agreements for DDR of armed groups in CAR that were never carried out. There was a lot of talk, a lot of planning, but the fighting continued. The government promised the fighters a DDR process but it never arrived, and many simply took up arms again. Now with a third agreement signed in 2015, there is still no clear plan to put it into effect. We have a new president who says a lot of the right things, but we need to see those words turned into action.

Do you see any hopeful signs for a more peaceful future and more effective government?

Mangan: The successful presidential election was a key event. The country is more stable. Some violent incidents that previously might have spiraled into broader conflict have been managed and controlled a bit better. But recent attacks are a concerning sign of more instability to come. It remains concerning that incidents like assassinations, kidnappings, and reprisal attacks continue among armed groups.

There is a dangerous cycle of violence in CAR. Each time an incident occurs—whether conflict-related or not—rival armed groups respond with disproportionate force, fueling periodic upsurges in violence. Most citizens are exhausted by war, impatient for progress and frustrated by lack of action. The honeymoon is definitely over for the new government.

What is the focus of USIP’s work in CAR and what are the results so far?

Mangan: USIP is encouraging the government to actively consult citizens as it shapes policy. This work was inspired by what we saw at the Bangui Forum—a big, national dialogue convened in May 2015 by transitional President Catherine Samba-Panza. In the run-up to the forum, citizens were asked, for the first time in CAR’s history, what they wanted, and their responses fed into the peace process.

This kind of citizen engagement shouldn’t only happen every 10 years when there’s a crisis. Governance is a conversation. So we set up a national-level group of senior civil servants and civil society and had them travel outside the capital to connect with local-level activities to foster consultation that we were carrying out in four towns.

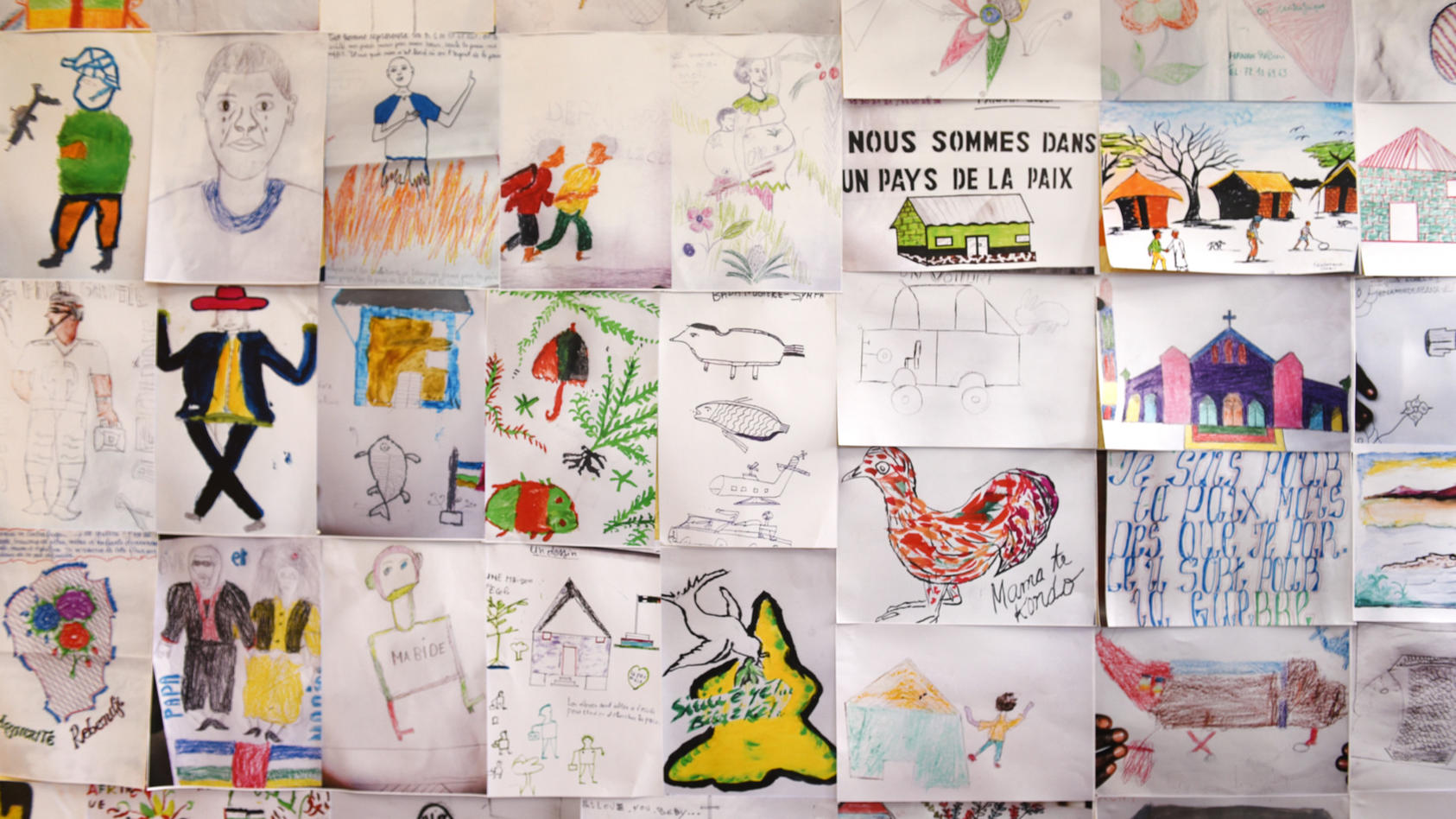

Acko: We explored a number of different methodologies for building effective citizen consultation in CAR. One focused on facilitated dialogue, where citizens had the opportunity to discuss community security issues, talk though local solutions and pass key messages, needs and desires to the central government. We also used participatory art, music, theater and documentary filmmaking as a form of research and consultation. Our final project component involved more classic research—interviews with the population, the authorities, the international community and the armed groups—to analyze the conflict and the security situation.

Can you talk a bit more about the process of “demobilizing, disarming, and reintegrating” the armed groups into society—“DDR,” as it's known?

Mangan: In the Central African Republic, they've added a second 'R' to their DDR plan, covering the believed need for repatriation of "foreigners" involved in armed groups. Mercenaries from neighboring countries were involved in the coup that brought the Séléka to power in 2013 and in previous coups, too. Many CAR officials and citizens believe that getting them out of the current conflict is key to the DDR process, but it is very complex. Neighboring countries may not take them back as many of them were involved in rebel movements at home.

The issue has also provoked a crisis over identity and the question of who is a Central African. Many of the mercenaries came to fight with the predominantly Muslim Séléka, provoking a backlash against the Muslim community in general, which make up approximately 15 percent of the population. Even before this latest conflict, there has long been discrimination against the Muslim community, with many being labeled foreigners, even when families have been in the country for generations. Additionally, some mercenaries associated with former coups were integrated into the armed forces and thus gained some legitimacy. It will be very complicated to manage, and there is real sensitivity around that repatriation issue.

What are some obstacles to DDR and what incentives can be offered to armed groups to quit the conflict?

Acko: Incentives are hard to figure out because they are tied to the obstacles, which include the conflict’s economic drivers. The armed groups’ leaders are accumulating wealth from the conflict through control of the cattle market, extortion, road taxes and mining of gold and diamonds. Neighboring states such as Chad, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon have links to different factions reaping some benefit, too. The last two attempts at disarmament involved basically a program of cash for guns, so the armed groups mistakenly expect that again. This time, the idea is to provide economic opportunities for demobilized fighters to really get them out of the conflict. The United Nations stabilization force is helping the government implement DDR.

Mangan: For the armed group commanders, who would have to order demobilization, we’re going to need something more substantial. Someone exacting $10,000 a day by taxing the cattle market and mounting tolls on key roads isn’t going to be enticed by offers to help set up a farm or small shop. There will need to be greater incentives for such individuals, deal-making or steps taken to put the conflict economy beyond play, preventing armed groups from controlling key marketplaces and the diamond fields.

A central demand of the armed groups is for integration into the security sector, in part to better balance its regional, ethnic and religious composition. This is a vital incentive but it is difficult — the army is a damaged organization, as are the police and the gendarmerie, which will struggle to integrate former combatants. Finally, greater political integration and inclusion of traditionally excluded Muslim communities, especially in the northeast, also is a longstanding grievance of armed groups that needs attention.

Are you concerned the international community will lose interest in CAR and feel the job is done after the election?

Mangan. Yes. We've seen this elsewhere. After a successful election, the international community seems to decide a country is fixed, and realistically CAR is not of wide strategic interest. CAR is one of those countries that unfortunately receives attention at crisis points but not much support in between, support that might move it ahead. In recent history, there have been two DDR failures there. We need to support this process on the ground and not lose interest at a critical juncture.

What’s happening with the Ugandan troops who, with help from U.S. special operations forces, deployed to CAR to stamp out the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA)?

Mangan: Only an estimated 120 LRA fighters are left in CAR, but they’re bush people and hard to track. Despite LRA activity, the southeast has been the most stable part of CAR in the past few years because Séléka never moved into the area, in part because of the U.S. and Ugandan forces’ presence. Now the Ugandans are talking about pulling out. They don’t see it as an important part of their foreign policy anymore.

Acko: The concern is that if they withdraw quickly, it will create a security vacuum in the southeast of CAR that neither the U.N. peacekeepers nor the barely operational army could fill. This could allow the LRA to regain its strength, and potentially we could see ex-Séléka armed group factions move into those areas.

What advice would you offer the CAR government, the U.N. and international partners moving forward from the European Union-led CAR donors’ conference that took place on November 17?

Mangan: I worry the international community is replicating some of the failures of the CAR government regarding where to target aid. To deal with fallout from the most recent crisis and the hardening Muslim-Christian sectarian divide, understandably we need to focus energy on the western part of the country, where currently most international aid efforts are centered. But the historic neglect of the east and northeast is where the root grievances of this conflict lie and must be resolved. And the international community is barely there. Government and international assistance focusing attention on those areas would start to send a message that “Our government cares about us.” In time, that may help to pull citizen support away from the ex-Séléka.

Acko: I also think we need international assistance in reorganizing the diamond trade. Part of what generated the most recent crisis was the decision by former President François Bozizé to close down diamond buying offices, seeking to exert personal control over the diamond economy. Many of the small miners in towns where diamonds were 80 percent of income suffered and opted to join the Séléka. We need to negotiate ways to develop a more well-functioning diamond trade, which will be key to bringing these fighters back into civilian society.