Hamas's landslide victory in the Palestinian parliamentary elections of January 2006 came as an unwelcome and unexpected shock to both Middle Eastern and international regimes, with the organization winning nearly 58 percent of the Palestinian Legislative Council seats. The United States, a number of European nations, and Israel had all issued clear warnings before the elections that they would not deal with a Palestinian Authority led by Hamas.

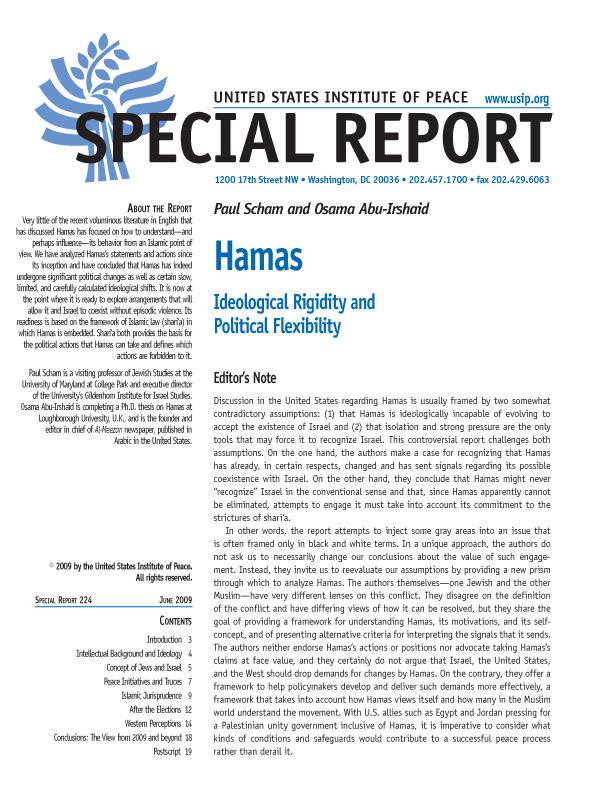

Editor's Note

Discussion in the United States regarding Hamas is usually framed by two somewhat contradictory assumptions: (1) that Hamas is ideologically incapable of evolving to accept the existence of Israel and (2) that isolation and strong pressure are the only tools that may force it to recognize Israel. This controversial report challenges both assumptions. On the one hand, the authors make a case for recognizing that Hamas has already, in certain respects, changed and has sent signals regarding its possible coexistence with Israel. On the other hand, they conclude that Hamas might never "recognize" Israel in the conventional sense and that, since Hamas apparently cannot be eliminated, attempts to engage it must take into account its commitment to the strictures of shari'a.

In other words, the report attempts to inject some gray areas into an issue that is often framed only in black and white terms. In a unique approach, the authors do not ask us to necessarily change our conclusions about the value of such engagement. Instead, they invite us to reevaluate our assumptions by providing a new prism through which to analyze Hamas. The authors themselves--one Jewish and the other Muslim--have very different lenses on this conflict. They disagree on the definition of the conflict and have differing views of how it can be resolved, but they share the goal of providing a framework for understanding Hamas, its motivations, and its selfconcept, and of presenting alternative criteria for interpreting the signals that it sends.

The authors neither endorse Hamas's actions or positions nor advocate taking Hamas's claims at face value, and they certainly do not argue that Israel, the United States, and the West should drop demands for changes by Hamas. On the contrary, they offer a framework to help policymakers develop and deliver such demands more effectively, a framework that takes into account how Hamas views itself and how many in the Muslim world understand the movement. With U.S. allies such as Egypt and Jordan pressing for a Palestinian unity government inclusive of Hamas, it is imperative to consider what kinds of conditions and safeguards would contribute to a successful peace process rather than derail it.

Even if readers accept the authors' interpretation of Hamas's thinking, many may still question whether engagement is worthwhile, particularly given--as the report describes--the limits for Hamas to compromise and the very real risk of renewed and potentially more dangerous conflict should a truce end. Others advocate engagement, even in Israel where the debate remains robust and diverse. Experience with intractable conflicts in Northern Ireland, Aceh, and elsewhere suggests that ideologically rigid movements can change over time and that a peace process itself can play a critical role in shaping such an evolution. The report argues that it is not inevitable that Hamas will accept coexistence, only that its acceptance is more likely if framed within its Islamic ideology.

In a region where hopes for peace have been raised and dashed again and again, cynicism is the biggest obstacle facing the Obama administration's new peace initiative. While no one should be expected to trust blindly, repeated failures to achieve a lasting solution to this seemingly intractable conflict suggest that a reexamination of our assumptions and our analytical frameworks is essential.

Summary

- Although peaceful coexistence between Israel and Hamas is clearly not possible under the formulations that comprise Hamas's 1988 charter, Hamas has, in practice, moved well beyond its charter. Indeed, Hamas has been carefully and consciously adjusting its political program for years and has sent repeated signals that it may be ready to begin a process of coexisting with Israel.

- As evidenced by numerous statements, Hamas is not hostile to Jews because of religion. Rather, Hamas's view toward Israel is based on a fundamental belief that Israel has occupied land that is inherently Palestinian and Islamic.

- For Hamas, "recognition" of Israel would represent a negation of the rightness of its own cause and would be indefensible under Islam. It considers unacceptable for itself the actions of those Muslim countries that have recognized Israel, such as Egypt and Jordan, and those that have indicated their willingness to do so, such as Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arab League, because they have provided no theological justification for their policies toward Israel.

- Although Hamas, as an Islamic organization, will not transgress shari'a, which it understands as forbidding recognition, it has formulated mechanisms that allow it to deal with the reality of Israel as a fait accompli. These mechanisms include the religious concepts of tahadiya and hudna and Hamas's own concept of "Palestinian legitimacy."

- Tahadiya refers to a short-term calming period between conflicting parties during which differences are not put aside. A tahadiya stopped most violence between Hamas and Israel from June to December 2008.

- Hudna is a truce for a specific period, which is based on the practice of the Prophet Mohammad and on subsequent events in Muslim history. Hamas has indicated on a number of occasions its willingness to accede to a hudna with Israel, assuming basic Palestinian rights as set forth in the Arab Peace Initiative (API) are agreed to first.

- Palestinian legitimacy is a term employed by Hamas to describe its willingness to consider accepting a binding peace treaty, such as the proposal set forth in the API, so long as the treaty is first ratified by the Palestinian people in a referendum. Although Hamas would not directly participate in peace negotiations with Israel, Hamas has indicated that it would be willing to be part of a Palestinian coalition government with Fatah under which Fatah would negotiate the actual treaty.

- Although a peace process under such circumstances might, for Israelis and Westerners, seem involved, arcane, and of dubious utility, it is necessary to consider the possibility of such a process because there is no realistic scenario under which Hamas will disappear. Understanding the Islamic bases of Hamas's policies and worldview will be essential for the success of any process in which it is engaged.

About the Report

Very little of the recent voluminous literature in English that has discussed Hamas has focused on how to understand--and perhaps influence--its behavior from an Islamic point of view. We have analyzed Hamas's statements and actions since its inception and have concluded that Hamas has indeed undergone significant political changes as well as certain slow, limited, and carefully calculated ideological shifts. It is now at the point where it is ready to explore arrangements that will allow it and Israel to coexist without episodic violence. Its readiness is based on the framework of Islamic law (shari'a) in which Hamas is embedded. Shari'a both provides the basis for the political actions that Hamas can take and defines which actions are forbidden to it.

Paul Scham is a visiting professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Maryland at College Park and executive director of the University's Gildenhorn Institute for Israel Studies. Osama Abu-Irshaid is completing a Ph.D. thesis on Hamas at Loughborough University, U.K., and is the founder and editor in chief of Al-Meezan newspaper, published in Arabic in the United States.