Jihadism has evolved dramatically and traumatically since the 9/11 attacks. Movements, leaders, targets, tactics, and arenas of operation have all proliferated in ways unimagined in 2001. The international community has mobilized unprecedented force against an array of jihadis, with mixed results. The United States alone has spent trillions of dollars—in military campaigns, intelligence, law enforcement, homeland security, and diplomacy—to counter jihadism. Progress has been made; fewer than a hundred people were killed inside the United States between 2001 and late 2016—in stark contrast to the death toll on 9/11. Yet the threat endures.

The emergence of the Islamic State—also known as ISIS, ISIL, or Daesh—transformed the world of jihadism. After capturing large swaths of Iraq and Syria in 2014, the Islamic State attracted tens of thousands of foreigners who sought to build a new Islamic society in a modern caliphate. They included engineers, accountants, teachers, grandparents, and teenage girls, as well as fighters. They reinvigorated existing jihadist movements and galvanized a new wave of support for jihadism generally. In 2014, ISIS seemed to eclipse al-Qaeda.

But al-Qaeda, the vanguard of the global jihadist movement, is seeking to reclaim its primacy. It has built support among local jihadist groups in the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and the Caucasus. Core leaders still provide overall directives, although they have also dispersed among affiliates. Advisors help groups define local goals and targets. Al-Qaeda has played the long game, and it may prove to be a more enduring model than the Islamic State.

Together, ISIS and al-Qaeda pose complementary threats to global security. But the jihadist spectrum is also far more diverse today than it was on 9/11. The danger is not just from this duo.

Local extremist groups are creating ever more complex variations of jihadism across the Middle East. Some invoke the global jihadist rhetoric of al-Qaeda or ISIS, while others are more nationalist. Some of these groups—such as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (JFS) and Ahrar al-Sham—are “country-first” jihadists, albeit with different levels of commitment to nationalist politics. Their immediate focus has been establishing institutions within the local communities where they have thrived, even if they have networks outside or connections abroad. For this reason, disentangling local Sunni communities from country-first jihadis will prove as challenging as routing out ISIS from cities in Iraq and Syria, as the United States and its partners are doing.

Another variation is the “marbling” of jihadi groups. Local country-first groups have fluid relationships with global jihadist movements—merge or cut ties with one another as is convenient. The shifts often happen for strategic, logistical, or financial (including salary-related) reasons rather than for purely ideological ones.

Regardless of the fate of ISIS and al-Qaeda, Sunni extremist movements have proliferated at a time when governments across the region are comparatively weak or vulnerable. Traditional forms of authority are being challenged; traditional forms of national identity are being redefined. New political spaces have emerged that are beyond the control of traditional governments. As a result, the region—politically and physically—is extremely vulnerable.

Key Points

- Jihadism initially focused on overthrowing local regimes; agendas gradually expanded to include transnational or transcontinental goals. For some, the short-term focus has again moved towards local goals and strategies. Local jihadist groups have also multiplied. Jihadism now has multiple models. But ISIS and al-Qaeda remain the two major global brands.

- Since 2013, al-Qaeda and ISIS have varied little in core ideology but have adopted divergent strategies and tactics. Al-Qaeda has sometimes capitalized on ISIS tactics—and made gains in unexpected ways.

- ISIS’s priority has been to destabilize regimes in order to control territory as quickly as possible. Its strategy is methodical even as its warfare has been irregular since 2009. It has created a new standard for nonstate actors and asymmetric warfare since sweeping across Syria and Iraq in 2014. But its initial strategy, as a long-term territorial project, may not be sustainable. Even if ISIS should fail this time around, a hardened core will attempt a comeback. Others may adopt its recipe too.

- The contraction of the Islamic State—the loss of part, or all, of its caliphate—may not fundamentally undermine its appeal. As an extremist organization, ISIS is likely to endure for years to come as a pure insurgency using terrorist tactics. It revolutionized mobilization of supporters and sympathizers in the West, a lasting legacy as well as a future threat.

- Al-Qaeda has overcome the critical challenges of bin Laden’s death in 2011 and the rise of ISIS in 2014. It has demonstrated an ability to evolve and adapt to shifting political trends in ways beyond the control of local governments, regional forces, or the international community.

- But al-Qaeda also may look vastly different as it relies increasingly on local allies and affiliates. It already exists in a form vastly different from 2001. Al-Qaeda has invested heavily in co-opting local Islamist movements and embedding within popular uprisings—even as its central command has continued to issue directives. It has sought to unite these local groups to support its own objectives. In the future, al-Qaeda has the potential to be a greater jihadist threat than ISIS.

- The Nusra Front in Syria has been the most successful test of this al-Qaeda model. Since 2012, its strategy has been a form of “controlled pragmatism.” Its rebranding—as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham in 2016—reflects al-Qaeda’s strategy of “guided transformation.” Al-Qaeda agreed to the rebranding, partly because Syrian rebels were uneasy with an al-Qaeda presence in their ranks.

- How al-Qaeda and ISIS rely on and respect popular support reflects a basic difference between them. ISIS coerces local populations while advertising to a global audience. It has created local governance. It has also targeted potential recruits around the world, with propaganda in dozens of languages weighing in on issues unique to Muslim communities in France, Russia, or elsewhere. But ISIS’s message is zero-sum: you are either with ISIS, or you are an infidel. It has been prepared to act ruthlessly against those who do not share its hard-line worldview. Its tactics are coercive. In the end, it tends to act unilaterally.

In contrast, al-Qaeda groups have focused more on local populations and local flashpoints. Al-Qaeda co-opts; it seeks local buy-in that makes the movement sustainable in the long term. Syria is a prime example: ISIS has ruled ruthlessly and killed with few restraints in its Syrian holdings. Al-Qaeda has positioned itself as an actor with higher moral ground—by building alliances with local militias and limiting collateral damage—in an incredibly brutal civil war. Al-Qaeda’s long-term objective is the same as the Islamic State’s: to reform society and govern it under a strict interpretation of sharia. They differ in methodology and timeline. - ISIS is a political extremist actor, while al-Qaeda has become an extremist political actor. In other words, ISIS is more of an extremist movement with political goals. ISIS is unwilling to compromise; its behavior is unlikely to change whatever the incentives. In contrast, al-Qaeda is now more of a political organization with extremist beliefs, although that does not mean it can be co-opted.

- Both ISIS and al-Qaeda have long-term strategies to create a Salafi utopia. ISIS’s core strategy is to pursue a Salafi state through continuous confrontation both within Muslim-majority countries and outside them. ISIS believes Muslims can be held to an interpretation of sharia today. It is more doctrinaire, less accommodating of non-Salafi trends. It looks on the Muslim Brotherhood founder as an infidel and at the Taliban as an infidel state. For ISIS, the means justify the ends; it has engaged in a war of attrition in Iraq and Syria.

- Al-Qaeda’s strategy is more gradualist. It believes that Muslims must be educated first on sharia, that the idea of jihad must be popularized, and that Muslims must be convinced to take up arms as the only method of emancipation. It is less exclusionary. It has forged alliances and quietly entrenched itself and its ideas within local communities with the aim of eventually building a pure Salafi state.

- The two movements are rivals, despite their jihadist ideologies. They compete for dominance. They play off each other’s successes and failures. ISIS portrays itself as more successful strategically than al-Qaeda. In only a few months, it seized territory and declared a caliphate, while al-Qaeda's achievements have been less visible since 2011. Meanwhile, al-Qaeda benefits from ISIS’s violence in two ways: It has been able to exploit the instability created by ISIS. Comparatively, it appears to be the more pragmatic actor.

- The two movements have complementary effects on the global jihadi Salafist network, however. They are both exploiting disenfranchised or disillusioned Sunni youth in the Middle East and abroad. They are both undermining the existing state system and contributing to expanding wars in the region. They are both normalizing the belief that violent jihad is necessary in order to defend the Sunni community globally.

- The rivalry between ISIS and al-Qaeda does not weaken the jihadist threat; it widens its scope.

The Phases

Jihadism has evolved through multiple phases since it emerged in the late 1970s. The first phase—the inception—featured ideologues, such as Sayyid Qutb and his protégés in the Egyptian prison system, who were not all Salafi. But they all promoted the exclusivist and violent rhetoric of “takfirism,” or excommunication of fellow Muslims.

A second phase—of cross-pollination—featured twin phenomena: the expulsion of Muslim Brothers from Arab states and their employment or education in Saudi Arabia or Kuwait, a process that married the theological rigor of Salafism with the political activism of the Brotherhood’s Islamism. The leadership of the Brotherhood rejected Qutb’s approach, however, and the mainstream Brotherhood is not now jihadist. At the same time, jihadism among other ideologies and movements was increasingly “Salafized” in the 1980s and 1990s; the use of violent tactics and the religious ideology began to merge. Many jihadists started to insist that only Salafi theology was legitimate, a position that put them at odds with the Brotherhood.

The third phase—of causation—began as Salafist activist ideas were spurred by historic events, including the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989 and the first Gulf War in 1990–91, when hundreds of thousands of American troops were based in Saudi Arabia. Both military operations involved atheists, non-Muslims, or infidels deploying in Muslim lands. During the Gulf War, the Saudi Kingdom in particular was perceived as betraying Islam, sparking a movement known as the Awakening.

The fourth phase—of realization—featured bold attacks, such as the 9/11 spectaculars on the World Trade Center, and the emergence of jihadism as the top security threat facing the Western world. To jihadists, the attacks were a vindication of their cause and a sign that more was possible.

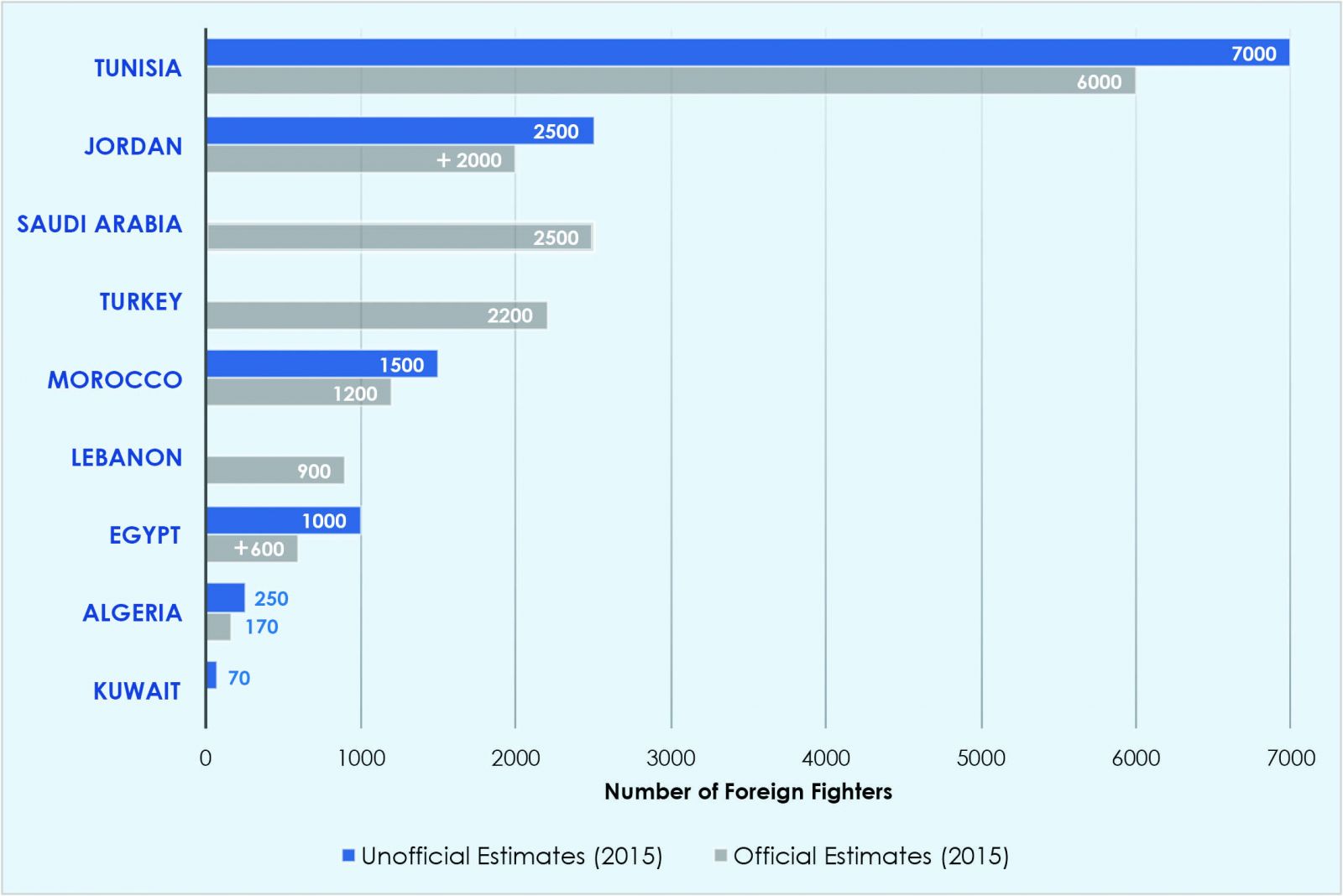

Figure 1. Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria by Country of Origin

Source: Official estimates from respective governments. Unofficial estimates are by the Soufan Group, “Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters into Syria and Iraq,” December 2015.

The fifth phase—of crossroads—occurred after the United States entered Iraq. It produced tectonic shifts in strategy, purpose, and identity among the jihadist groups—shifts that are still being witnessed.

Over time, motives and inspiration have diversified too. What drove fighters to join Osama bin Laden and the original Arab mujahideen in Afghanistan in the late twentieth century often varies significantly from what drove people to join groups such as ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria or Iraq in the early twenty-first century. The current jihadis are now part of a third generation.

The latest generation is distinct from the earlier waves in several ways. In sheer numbers, each mobilization of foreign fighters has been larger than its predecessor. The growth is now exponential, with surviving fighters of previous generations becoming important catalysts for the next generation. The pattern suggests that any new jihadi conflict will draw greater numbers than the last. Recruitment is also likely to surge because the best recruiters of new foreign fighters are former ones.

Each mobilization of fighters has also been faster. The time required for jihadis to act or swarm to a theater of conflict has been roughly halved with each foreign fighter mobilization. The ease of global travel and the interconnectivity of social media have solved the coordination challenges for global mobilization.

The foreign fighter pool has also diversified with each jihadi conflict. The first generation of jihadis, galvanized by Afghanistan, was predominantly from the Arabian Peninsula; its members were often referred to as “Afghan Arabs.” Gulf fighters have always constituted the largest constituency among foreign fighter populations. But the Gulf fighter proportion has decreased with each mobilization. For example, more fighters joined ISIS from Tunisia than from Saudi Arabia.

The number of North Africans dramatically increased during the fight against the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq. North Africans constituted roughly a fourth of all recruits. Between 2012 and 2015, Central Asians and particularly Europeans mobilized in unprecedented numbers to join the ranks of the Islamic State—a troubling development for Western countries.

Each generation has also grown more extreme.1 This trend is not specific to jihadi groups. From the 1970s to 1990s, Palestinian groups and Islamic extremist groups in Algeria underwent a similar process. Groups splintered; younger fighters grew impatient with the older generation and sought to make their own mark. Upstarts planned larger and executed more brazen attacks to outpace their forefathers. ISIS and al-Qaeda have followed a similar pattern, with the youngest fighters being ever more aggressive with each mobilization.

In the future, jihadis are likely to spread out to more locations or similar causes. Jihadism is a profession as well as a belief system. Once mobilized, a wave of foreign fighters is often difficult to demobilize. And foreign fighters who do demobilize are likely to remain an important part of the fabric of modern jihads, becoming facilitators or supporters who push the agenda forward, even if they do not join the fight itself.

Notes

- . Clint Watts, “Deciphering Competition between Al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State,” CTC Sentinel 9, no. 7 (July 2016), www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/deciphering-competition-between-al-Qaida-and-the-islamic-state.