Just outside Washington D.C., Arlington County encourages residents to practice a “Car-Free Diet” on occasion. I practiced a “car-free diet” for more than two years when I lived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The most recent wave of protests by Saudi women to press – again – for the right to drive sheds light on the battle of values playing out in the public squares (and on the roads) of the reclusive Kingdom. The outcome of this struggle has consequences well beyond Saudi society, because it frames the contributions that women are allowed to make.

When I first arrived in Riyadh in late 1985 as an Air Force lieutenant, I lived in a small housing complex, and the U.S. military provided my transportation most of the time. But when I used public transit, I had to sit in a separate section for women at the back of the bus. Because I’m a woman, I wasn’t allowed to drive under Saudi laws.

To understand how such a restriction could have come about, I tried to learn as much as I could about Saudi history, customs and culture. I read explanations that referred to Saudi customs related to women as outmoded vestiges of a tribal, Bedouin legacy; others lauded what they saw as Islam’s efforts to improve the status of women by ensuring their protection financially and socially.

Fast-forward almost 15 years to 1999, when I arrived in Riyadh again. Not much had changed. Many more cars packed the roads, yet women were still not permitted to drive. As a diplomatic spouse this time, my life was filled with perks, but a driver was not among them, except for my husband when he had time to play chauffeur.

So I took to riding my bicycle. I was told that even that could be construed as driving, but fortunately I was never run off the road as my predecessor was. She was convinced it was because the car driver felt offended to see a woman on a bicycle.

My frustration about not being able to drive initially revolved around caring for my three children under age five. Sometimes they needed medications I didn’t have in the house. Or I wanted to take them to an indoor play area rather than expose them to the 100-plus degree heat of our concrete carport. Sometimes I just needed one extra ingredient for dinner.

As time wore on, my frustration broadened to more philosophical concerns: my lack of freedom and my dependence on others. I had been warned in pre-deployment briefings about the impact this loss could have on me. But I didn’t anticipate the depth of it.

I found myself exercising my own forms of civil disobedience. I rode my bicycle with my young daughter strapped in her baby seat and my twin boys riding small bikes behind me, like ducklings behind their mother. We cruised into the middle of the traffic circle, with me stopping traffic by holding my hand outstretched like a road guard and waving my boys through the intersection. Once I drove across an expanse of desert, as I had seen Bedouin women doing, because people there looked the other way, for whatever reason.

Some days I called my husband, begging him to please take me and my energetic kids out of the house -- anywhere, fast. At the height of my exasperation, I got into the driver’s seat of my car when it was parked in our concrete carport, turned the car on, and simply inched back and forth until the frustration passed.

A friend gave me an English copy of the Quran, which I thought might enlighten me on why women couldn’t drive. I read the passages in the chapters (suras) about women’s rights, but of course there are no clear prohibitions against women driving, since the Quran dates to the 7th century A.D. It didn’t help.

One of the many ironies is that, if the ban on women driving is a vestige of Arab codes of honor that prohibit females from being in the company of non-relative men, women who cannot drive are placed in situations where non-family drivers, often foreign men, become almost constant companions of the women they ferry around.

The path to women driving in Saudi Arabia has been long and arduous, but at least the effort has come from within. I applaud my Saudi sisters for their patience.

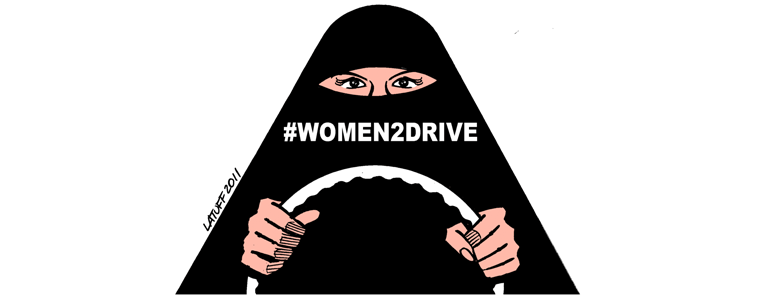

I met women who drove in the 1990 protest. The backlash that time was severe, with women arrested or losing their jobs, according to the BBC, which counted the day of driving last month as the third such protest counting the action in 1990. Publicly, the women did stop, but the desire for freedom never passed.

King Abdullah has moved Saudi society forward in many ways, and the decision he ultimately makes on this issue should be part of his legacy. So far this time, there are no reports of arrests despite more than 60 women taking part across the country and multiple videos posted on YouTube showing them veiled behind the wheel.

I encourage anyone -- a Saudi man, for example -- who is uncertain about their stance on the issue to try a car-free diet. Do it for a day. Then try it for a week. Then try it for two years. Or a lifetime.

Clearly, the time has come. Saudi sisters are standing up for freedom, and Saudi men should stand up beside them.

Jacqueline H. Wilson is a senior program officer in USIP’s Academy for International Conflict Management and Peacebuilding.