Libya’s Criminal Economy of Arms, Drugs, People Shakes Prospects for Transition

"What are black markets? They are people's markets." The declaration by then-Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi illustrates one of the many reasons it will be difficult to end Libya's illicit trade in drugs, weapons and people. In a new USIP report, Mark Shaw and Fiona Mangan use more than 200 interviews with Libyan smugglers, detainees, port managers, security officials and others to map trafficking in the region and explain how it hurts the transition to democracy.

Since the people's revolution that removed Gadhafi from power and ended autocratic rule in Libya, further political, social and economic progress has been hampered by security concerns. The new report by Shaw and Mangan, Illicit Trafficking and Libya's Transition: Profits and Losses, reveals how organized criminal activity and underground economies disrupt democratic political processes and impede state-building.

Understanding the complexities that connect illicit trafficking and smuggling with Libya's economic, social, and political dynamics is critical to identifying possible solutions both from within Libya and with assistance from the international community.

The authors' interviews, conducted across Libya, show the patterns of illicit trafficking in the region. In addition to smugglers, detainees, port managers and security officials, the researchers also spoke with police, coast guard officers, prison and immigration officials, migrants and other interviewees who described the deep entrenchment of illegal markets in Libyan society and politics.

Although Libya's criminal economy has a long history, it has evolved since the fall of the Gadhafi regime. Until the revolution, the illicit economy was effectively state sponsored—black market goods met some consumers' needs, while the state benefited by collecting payoffs and providing access to trade routes for political gain. The authors quote a 1988 address by Gadhafi: "As far as we are concerned as revolutionaries, [black markets] show that the people spontaneously take a decision and, without government, make something which they need … What are black markets? They are people's markets." This context deeply informs the difficulty of combating organized crime.

Even amid the transition to democracy, trafficking is considered a normal way of transferring resources, resulting in few social or cultural checks on certain kinds of illegal activity. State institutions still lack both authority and structure, and local leaders maintain considerable power over their regions outside of the central government.

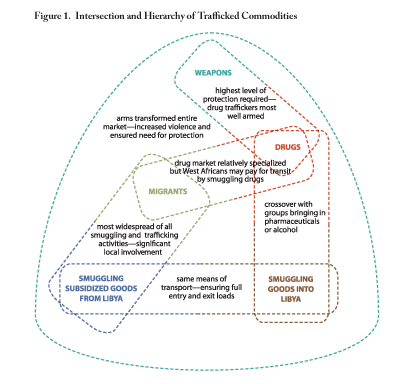

What has changed? Shaw and Mangan point to the decentralization of control over trafficking and smuggling, and how it has resulted in four interconnected markets in weapons, migrants, drugs, and smuggled goods.

The movement of goods into, out of, and through Libya is tightly linked, no matter the commodity. In many cases, the same transportation and organization is used in both directions, often with the cooperation of communities at the border.

Smuggling is an important source of commodities and resources for some communities, and the authors say volume has increased, as state services are still inadequate. Some smugglers profit by moving subsidized commodities out of Libya. Contraband like cars, alcohol and prescription medication are brought into the country.

Traffickers also use the organizational frameworks from smuggling to move other, more dangerous, goods. Additionally, increased reliance on illicit economies discourages community investment in the state and has a corrupting influence on officials and authorities.

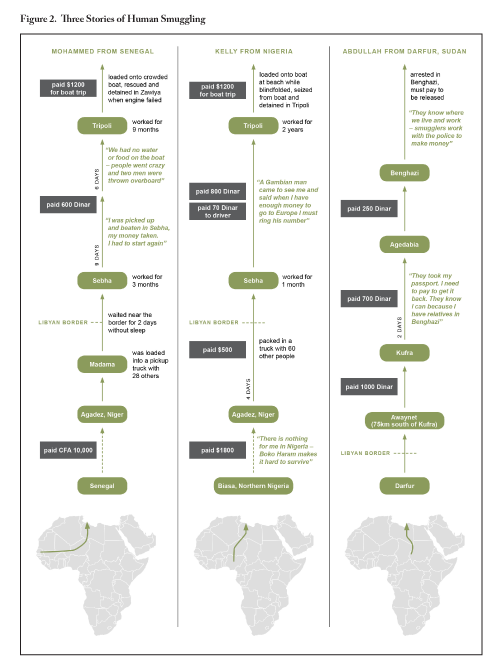

Migrant smuggling and illicit markets are tightly linked. Penalties for engaging in smuggling of migrants are less severe than for other offenses, and migrants often provide labor for traffickers or transport drugs in order to pay for their passage. Stories recorded from interviews with migrants show how their journey leaves them vulnerable to danger, abuse and violations of their human rights.

The link between smuggling migrants and the drug trade is clear from these narratives. Libya has a market for hashish, heroin, cocaine and prescription drugs, and the amounts of money at stake in the drug trade could be used to gain political influence.

Interestingly, the authors find there is not much crossover between the hashish dealers and those in the more-lucrative cocaine and heroin trade. The report quotes a former smuggler as saying "Drugs are for the big guys. You can't get involved, and you will lose your life if you try. The profits are too high and the people too powerful." Although increased drug trade is a concern, stronger state institutions can prevent it from growing and corrupting the political system.

Drug trafficking is also entwined with the market for protection and weapons trafficking. After the revolution, weapons moved out of the country and prices increased. More competition among smugglers has made weapons necessary to protect territory.

"You did not have to be armed in the past, but now it is essential to conduct business," said one smuggler, who now has a full-time bodyguard, to the authors. "There is a great deal of competition in the market."

Protection and safe trade routes are now commodities themselves. Bodyguards for traveling through contested territories, safe passage across enemy terrain, and guidance in adjacent communities all come at a price.

Although the USIP report summarizes the broader trends in Libya, Shaw and Mangan are cognizant of the unique dynamics of different areas of the country and Libya's impact across Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, and beyond.

Any solution to illicit trafficking in Libya must offer political and economic alternatives that create legitimate financial opportunity for the people and strengthen state institutions. Legal, judicial, and police solutions will not be enough.

Paula Burke is the marketing coordinator for publications at USIP.