A scandal involving murder allegations against the president and escalating violence from drug trafficking threaten Guatemala’s stability. Former USIP grantee Anita Isaacs recently traveled to the Central American country, where she witnessed massive demonstrations that exposed the fragility of Guatemala’s democracy.

June 2009

Anita Isaacs, former USIP grantee, writes about how the presidential scandal in Guatemala shines a spotlight on the country's efforts to deal with its painful wartime past.

.jpg) Murder allegations against Guatemala's president threaten to topple the government and further intensify the deep divisions in a country still recovering from a 36-year civil war. The allegations stem from a recent video in which a prominent lawyer, Rodrigo Rosenberg, accused Guatemalan President Álvaro Colom and three others of murder and corruption.

Murder allegations against Guatemala's president threaten to topple the government and further intensify the deep divisions in a country still recovering from a 36-year civil war. The allegations stem from a recent video in which a prominent lawyer, Rodrigo Rosenberg, accused Guatemalan President Álvaro Colom and three others of murder and corruption.

Rosenberg, who recorded the video just days before he was shot dead, said in the video: "If you are hearing or seeing this message, it is because I was assassinated by President Álvaro Colom."

President Colom has denied any involvement in Rosenberg's murder and says the allegations are part of a right-wing plan to remove him from office.

In mid-May, I traveled to Guatemala just after the video emerged, and witnessed two major demonstrations in the nation's capital that reminded me just how present Guatemala's tragic past is.

I first went to Guatemala through my USIP grant in 1997 to study how local and international NGOs could help build peace, but over time my work evolved to focus on Guatemala's struggle to confront its wartime past. My research now explores the relationship between accountability for wartime human rights violations and democratization. I am particularly interested in understanding how these processes, described as transitional justice, can contribute to sustainable peace and deepen democracy.

Those demonstrations in May 2009 evoked a Guatemala of the 1940s and 1950s -- a polarized, intransigent Guatemala that could well experience renewed armed conflict, and a country that was far from recognizing and dealing with its bloody past. The demonstrations illustrated to me that the wounds of Guatemala's 36-year civil war are far from healed and the country is still grappling with many of the same issues that manifested decades ago.

In the nation's plaza, one side of protesters demanded President Colom's resignation; the other side was showing their support for Colom, the nation's first leftist president in 50 years.

Both of the demonstrations occurred about a five-minute taxi ride apart -- though both sides may have well been worlds apart.

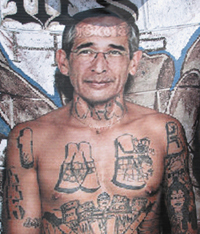

Anti-government protesters were calling Colom a gangster, as they paraded a banner with Colom's face superimposed over a tattooed gang member, and another declaring him an assassin.

Anti-government protesters were calling Colom a gangster, as they paraded a banner with Colom's face superimposed over a tattooed gang member, and another declaring him an assassin.

They demanded that those responsible for Rosenberg's assassination be brought to justice, although many seemed willing to dispense with an investigation, having already concluded that the president and his wife were responsible and that Colom should resign. Speakers called for a national strike to bring down the president, and one or two even appealed for a military intervention. The demonstrators portrayed their mission in contradistinction from that of Colom's supporters -- and that they were pursuing justice in the face of impunity.

These 30,000 or so anti-government protesters wore white tee-shirts and labeled themselves "Los Blancos." They called themselves Los Blancos because they wanted to identify themselves with a struggle for peace and justice, rather than wear black that would have symbolized people in mourning. Curiously though, the "blanco" label conveyed a rather different meaning to me, as an outside observer: It was hard to detect an indigenous face among the "white" mostly urban, crowd, reminding me of the entrenched racial and ethnic socioeconomic divides.

These were mostly Guatemalans of relatively good economic means who were also not direct victims of the country's 36-year armed conflict, during which genocide had been perpetrated against the country's indigenous population. Notably, when asked about the parameters of the justice they pursued, they insisted that it was not about seeking justice for wartime human rights abusers -- that was the "past" but today, they wanted justice for Rosenberg's assassins.

Meanwhile, the parallel demonstration, of at least 25,000 pro-government supporters, was staged in front of the presidential palace.

Unlike "los Blancos," these protesters were not dropped off by chauffeurs, nor had they walked a relatively short distance from their capital city homes. Instead, the pro-government demonstrators had been bused in from often remote hamlets in the Guatemalan countryside, as part of a massive, and expensive, government mobilization effort.

.jpg) The contrast between the two groups was stark, reflected in their rural origins, their mostly indigenous makeup, their colorful dress, and their poverty. Many of these were survivors of the civil war who hope one day to see justice served for those responsible for the deaths and disappearances of their relatives. Their banners did not ask for justice for Rosenberg. Instead they conveyed anger against "los ricos" -- or the rich -- who were seeking to overthrow the president, and they described Colom as a president of the poor, and of the people. They urged him to stand his ground, and to stand with them, as they did with him.

The contrast between the two groups was stark, reflected in their rural origins, their mostly indigenous makeup, their colorful dress, and their poverty. Many of these were survivors of the civil war who hope one day to see justice served for those responsible for the deaths and disappearances of their relatives. Their banners did not ask for justice for Rosenberg. Instead they conveyed anger against "los ricos" -- or the rich -- who were seeking to overthrow the president, and they described Colom as a president of the poor, and of the people. They urged him to stand his ground, and to stand with them, as they did with him.

The polarization reflected in these parallel marches is a painful reminder of a society still at war with itself.

It also speaks to a missed opportunity for unifying the country -- and bridging the ethnic, socioeconomic divides -- in the face of escalating violence in a country where some 18 people are murdered every day.

Crime committed by networks of gangs, drug traffickers, and other criminal elements is spiraling out of control. It targets those who speak out against impunity, but it also hits indiscriminately -- affecting the rich who feel tremendous insecurity as they go about their daily lives amid random acts of violence, as well as the poor who become victims of extortionist violence.

The crime wave is something they have in common, yet Guatemalans do not recognize it as a shared concern. Instead of taking advantage of this mutual interesting, and coming together as members of a country under siege to demand an end to violence and impunity -- the traditional fissures in Guatemalan society erupt, manipulated by various political actors with their own agendas.

What I found both most interesting and most distressing about what's happening now is how these two protests expose the same fault lines and divisions that existed during the armed conflict.

I realized then that Guatemala is as much as ever at war with its past. I saw first-hand how the process of truth seeking, for instance, has emboldened poor, indigenous survivors of the war. They found a voice, and their leadership understood that this unity afforded the power of numbers. But they have been reminded as always that they face an uphill battle, as they contend with a wealthy elite determined to retain their historical control over the economic and political levers of power.

The demonstrations project the same snapshot of societal divisions and a struggle for power that have shaped the pursuit of justice for wartime violations of human rights.

As long as the same fault lines prevail, the future of peace and democracy hang in the balance.

Read Anita Isaac’s Prepared Remarks to the House Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere (.doc 56 KB)