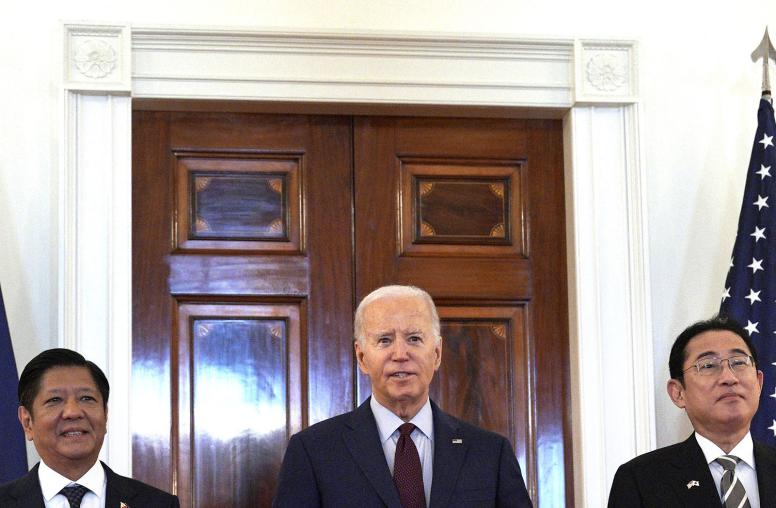

North Korea tested a ballistic missile this morning, just one day before President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping meet for the first time. The U.S. and China each blames the other for failing to curb North Korea’s missile and nuclear threat, and Pyongyang is testing their will to compromise. This summit is an opportunity for both leaders to commit to a serious discussion about meaningful action.

There are no easy options on North Korea. Both the U.S. and China oppose North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs, but they disagree as to which country has the ability to stop them.

Washington points to China’s overwhelming economic leverage over North Korea, but China insists it cannot convert that economic power into policy change without risking regime collapse. Instead, Beijing has pressed Washington to solve the problem diplomatically. This approach could include formal recognition of North Korea, security assurances, or an end to military exercises with South Korea. But the U.S. is unlikely to negotiate without first receiving meaningful concessions from Pyongyang.

By refusing to act, China is trying to goad the U.S. into taking the first step. Conversely, by threatening more aggressive efforts, Washington is trying to intimidate Beijing into adopting stronger policies.

Pyongyang is unlikely to surrender its nuclear program under any conditions. But a well-designed combination of carrots and sticks offered in concert by China and the U.S. might lead to a freeze. To implement that approach, Washington and Beijing should begin talking about the terms under which each country would be willing to enter into direct negotiations with Pyongyang, as well as discussing the possibility of more coercive diplomatic or economic measures and ideas for preventing the North Korean people from suffering further at the hands of their government.

Consider Negative Outcomes

The two countries also need to consider negative outcomes. In the past, China has refused to hold discussions with the U.S. on contingency plans for a potential war or political crisis on the peninsula. But both sides should start talking about what a post-war or post-collapse settlement might look like, as well as strategies to secure North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

All three countries are attempting to call one another’s bluff. China halted coal imports from North Korea earlier this year and likely pressed Pyongyang not to test a missile or nuclear weapon around this week’s summit. This morning’s missile launch sends a powerful signal to Beijing about the limits of its influence.

Trump has indicated clearly that he intends to take a tougher approach. His recently completed North Korea policy review includes options for secondary sanctions against Chinese entities that support North Korean activities, as well as increased deterrence through enhanced missile defense in South Korea and Japan. At the same time, it de-emphasizes direct military action.

North Korea’s repeated tests—including a possible nuclear test in the coming days or weeks—dare both Washington and Beijing to take action. Instead of waiting for the other side to make the first move or for better choices to emerge, both need to do more and increase their cooperation if they hope to halt or slow Pyongyang’s steady march toward more advanced nuclear and missile capabilities.